Jacemedical.com

Meta-Analysis of Multiple Primary Prevention Trials of

Cardiovascular Events Using Aspirin

Alfred A. Bartolucci, PhD,a,* Michal Tendera, MDb, and George Howard, DrPHa

Several meta-analyses have focused on determination of the effectiveness of aspirin (ace-

tylsalicylic acid) in primary prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. Despite these data,

the role of aspirin in primary prevention continues to be investigated. Nine randomized

trials have evaluated the benefits of aspirin for the primary prevention of CV events: the

British Doctors' Trial (BMD), the Physicians' Health Study (PHS), the Thrombosis Pre-

vention Trial (TPT), the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study, the Primary

Prevention Project (PPP), the Women's Health Study (WHS), the Aspirin for Asymptom-

atic Atherosclerosis Trial (AAAT), the Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease and

Diabetes (POPADAD) trial, and the Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With

Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) trial. The combined sample consists of about 90,000 subjects

divided approximately evenly between those taking aspirin and subjects not taking aspirin

or taking placebo. A meta-analysis of these 9 trials assessed 6 CV end points: total coronary

heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), total CV events, stroke, CV mortality,

and all-cause mortality. No covariate adjustment was performed, and appropriate tests for

treatment effect, heterogeneity, and study size bias were applied. The meta-analysis suggested

superiority of aspirin for total CV events and nonfatal MI, (p <0.05 for each), with nonsignif-

icant results for decreased risk for stroke, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality. There was no

evidence of a statistical bias (p >0.05). In conclusion, aspirin decreased the risk for CV events

and nonfatal MI in this large sample. Thus, primary prevention with aspirin decreased the risk

for total CV events and nonfatal MI, but there were no significant differences in the incidences

of stroke, CV mortality, all-cause mortality and total coronary heart disease.

2011 Elsevier

Inc. All rights reserved. (Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1796 –1801)

The aim of the present analysis was to examine the more

Features of the studies included in the 9 trial

recent trials that have been published since Bartolucci and

meta-analysis are listed in

and add data from those studies to enlarge the

The United States Preventive Services Task de-

sample and thus the power and precision. By adding these

scribed the data collection and analysis from the first 5 primary

studies, it may be increasingly possible to detect moderate,

prevention trials—the British Doctors' Trial (BMD), the Phy-

but potentially meaningful, differences that individual trials

sicians' Health Study (PHS), the Thrombosis Prevention

cannot detect. Added studies to our meta-analysis of the 6

Trial (TPT), the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT)

primary prevention studies include the Aspirin for Asymp-

study, the Primary Prevention Project (PPP)—and the ad-

tomatic Atherosclerosis Trial the Prevention of

dition of the new data from the Women's Health Study

Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes

(WHS) was described by Bartolucci and The new

trial, and the Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclero-

sources of data are from the AAAT, POPADAD, and JPAD

sis With Aspirin for Diabetes trial.

Because aspirin may have a differential effect on differ-

ent aspects of cardiovascular (CV) disease, outcomes were

In this report, we present a meta-analysis of 9 pri-

classified as follows: (1) total coronary heart disease (CHD)

mary prevention trials with aspirin, including the AAAT,

as nonfatal and fatal myocardial infarction (MI) and death

POPADAD, and JPAD trials, added to the 6 trials in-

due to CHD; (2) nonfatal MI as confirmed MI that did not

cluded in the previous meta-analyses (the Antithrombotic

result in death; (3) total CV events as a composite of CV

Trialists' Collaboration and Bartolucci and

death, MI, or stroke; (4) stroke as ischemic or hemorrhagicstroke that may or may not have resulted in death; (5) CVmortality as death related to CHD or stroke; and (6) all-

aDepartment of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of

cause mortality as death related to any cause. Where appli-

Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama; and b3rd Division of

cable (data available), we performed a meta-analysis and

Cardiology Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland. Manuscript

summary overview for each of these end points for the 9

received December 14, 2010; revised manuscript received and accepted

study data sets. All 9 studies were screened for these out-

February 12, 2011.

This study was supported by an unrestricted research grant from Bayer

Data from the United States Preventive Services Task

HealthCare AG (Leverkusen, Germany).

*Corresponding author: Tel: 205-934-4906; fax: 205-975-2540.

Force for each patient trial and data from the WHS, AAAT,

E-mail address: (A.A. Bartolucci).

JPAD, and POPADAD were combined for analysis. For

0002-9149/11/$ – see front matter 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Preventive Cardiology/Meta-Analysis of Aspirin in Primary Prevention

Table 1Features of the trials included in the 9 study meta-analyses

6-Study* Meta-Analysis

Aspirin dose (mg/dl)

75–300; 100–325

Healthy men/women, DBP

Men/women, low brachial index

Type 1 and 2 diabetes

* Details of the 6 individual primary prevention trials (WHS, BMD, PHS, HOT, PPP, and TPT) are given in Bartolucci and DBP ⫽ diastolic blood pressure.

Statistical significance of cardiovascular end points in the primary

Meta-analysis of predefined end points for the 9 study meta-analysis

prevention trials

All-cause mortality

* Coronary and cerebrovascular death only.

neity across the studies, between-study variation, and

X ⫽ statistically significant advantage of aspirin versus placebo

within-study variation or patient selection. However, given

(p ⬍0.05).

the summary data, within-study variation is not easily as-sessed. The standard procedure for the assessment of small

each previously described end point, a meta-analysis was

study effects (i.e., a trend for relatively smaller studies to

performed for the comparison of aspirin with placebo or

show larger treatment effects) has been the use of funnel

control. A summary odds ratio with 95% confidence inter-

plots using Egger's There has been considerable

val was calculated. The odds ratio is the appropriate effect

discussion regarding the properties of this The

size statistic for our 5 risk ratio outcomes noted in the

technique of Macaskill et was used to adjust for this

previous paragraph. The odds ratio is the ratio of the odds of

shortcoming (also see Harbord et

an event occurring in 1 group to the odds of it occurring inanother group. The term is also used to refer to sample-based estimates of this ratio. Obviously, an odds ratio of 1

would indicate even odds or no difference between the 2

Among the 9 trials in the analysis, 50,868 subjects were

groups of aspirin and control with respect to the odds of anevent such as MI. Calculation of the overall effect combin-

treated with aspirin and 49,170 received placebo or control.

ing the 9 studies used the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square sta-

lists each study and indicates if statistical signifi-

tistic with 1 degree of freedom. This test does not assume

cance of aspirin versus placebo was reached when using the

that patients in 1 study can be directly compared with those

odds ratio for any of the end points or groups of end points.

in another study, and it does not assume that any treatment

The combined effects of aspirin on these end points are

effects are similar in different studies. It does not assume

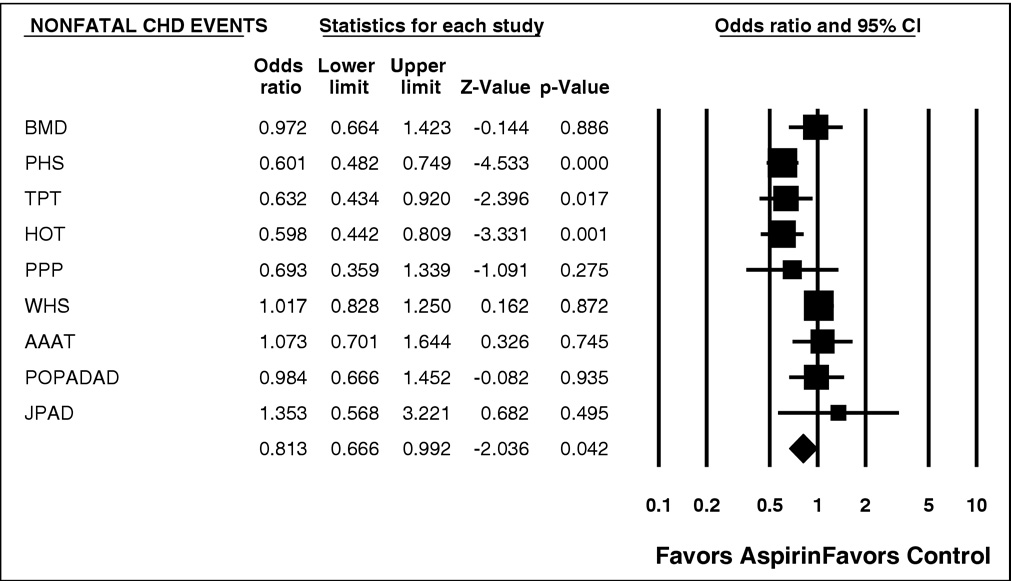

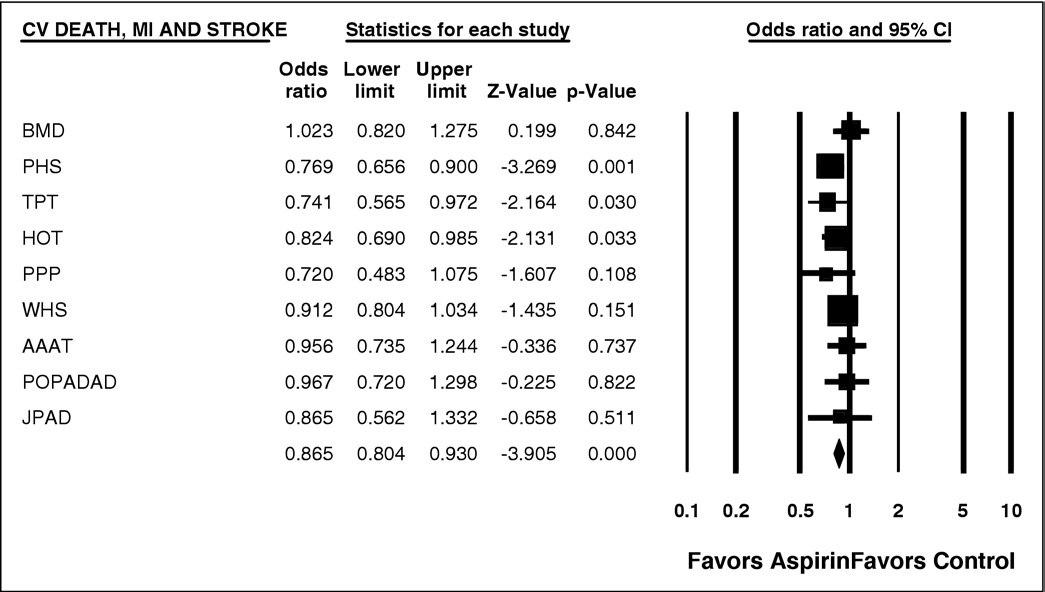

listed in In subjects treated with aspirin, there was

homogeneity but does take into account heterogeneity. Het-

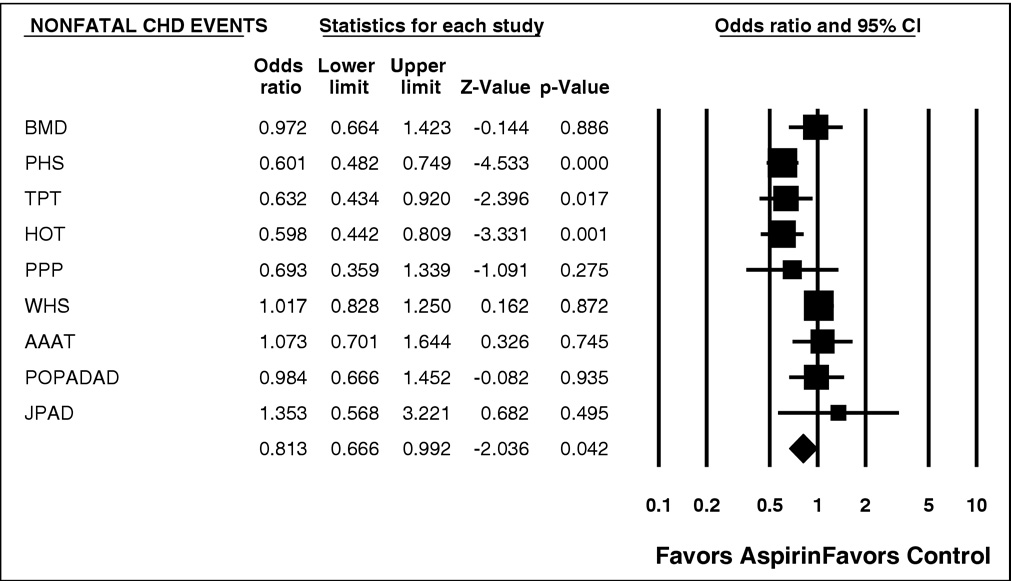

significantly decreased risk for nonfatal MI (p ⫽ 0.042) and

erogeneity was calculated using the chi-square test with n ⫺

total CV events (p ⫽ 0.001). There was significant hetero-

1 degrees of freedom, where n represents the number of

geneity (p ⱕ0.01) for several of the end points listed in

studies contributing to the meta-analysis. Forest plots were

(e.g., for total CHD events and nonfatal MI). The

used to assess if there was significant heterogeneity (defined

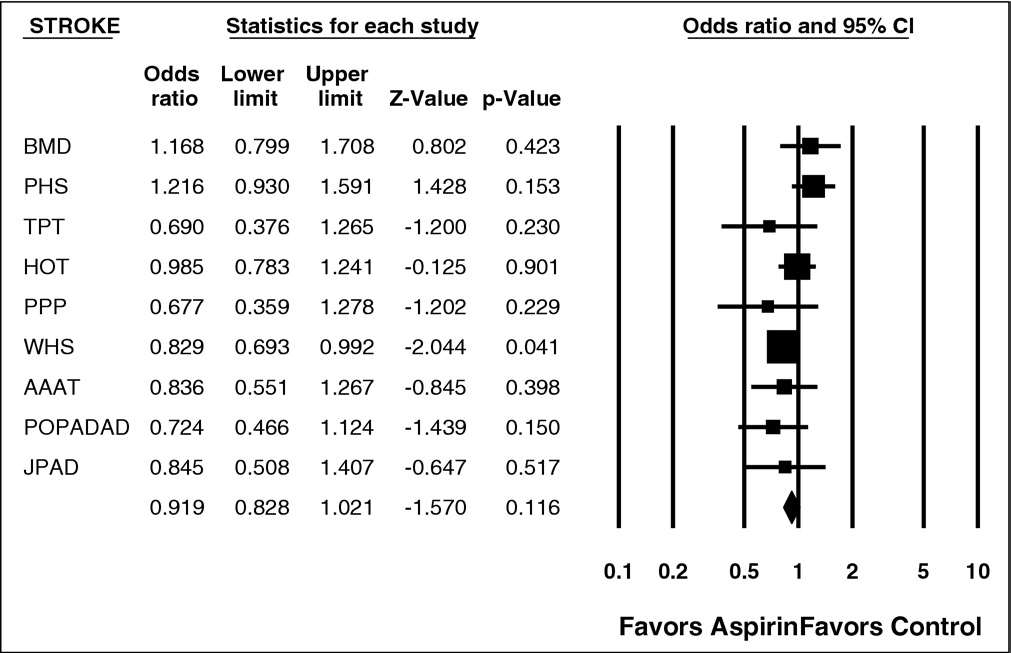

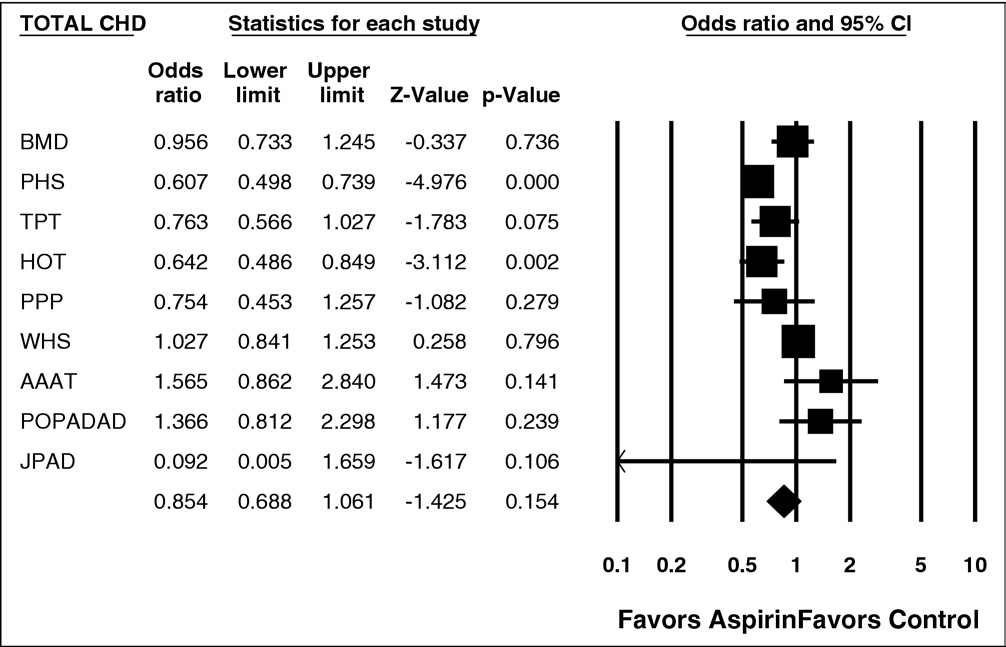

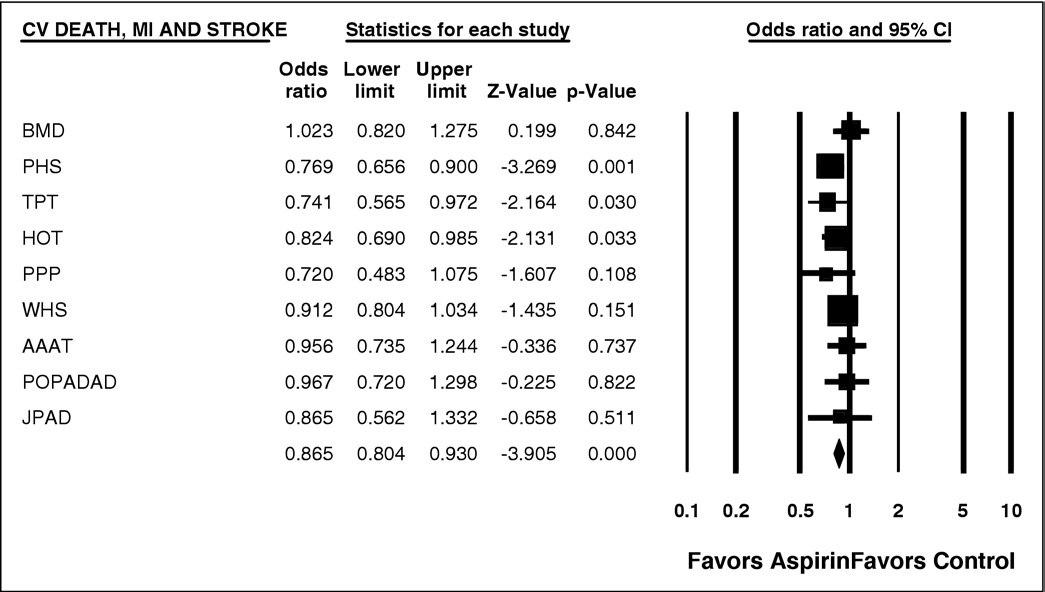

data for nonfatal MI and total CV events are shown in

as p ⬍0.01) and allowed assessment by considering the

and respectively.

direction of the results. A weighting factor was also used

to present different outcomes in the studies

that depended in part on the size of the study, which in turn

included in the current meta-analysis. They show that most

affected the inverse variance formula that the Mantel-Haen-

studies have odds ratios ⬍1, with an overall advantage of

szel procedure uses to calculate heterogeneity. The random-

aspirin over placebo. We had the ability to reexamine our

effects model also helps further account for the heteroge-

results with respect to previous risk for CHD in studies that

The American Journal of Cardiology (www.ajconline.org)

Figure 1. Forest plot of nonfatal CHD events. CI ⫽ confidence interval.

Figure 2. Forest plot of CV deaths, MI, and stroke. CI ⫽ confidence interval.

included TPT, PPP, AAAT, POPADAD, and JPAD, and we

We included the 2 trials conducted in patients with diabetes

found no change in our results. The remainder of the studies

mellitus and no symptoms of CV disease (POPADAD and

showed no previous risk for CHD. The results were consis-

JPAD). Although patients with diabetes might represent a

tent with those listed in all in favor of aspirin.

population different from those with high CV risk on the basisof the presence of classic risk factors alone, the studies clearly

represent the primary prevention setting.

It is evident that aspirin is beneficial for patients who

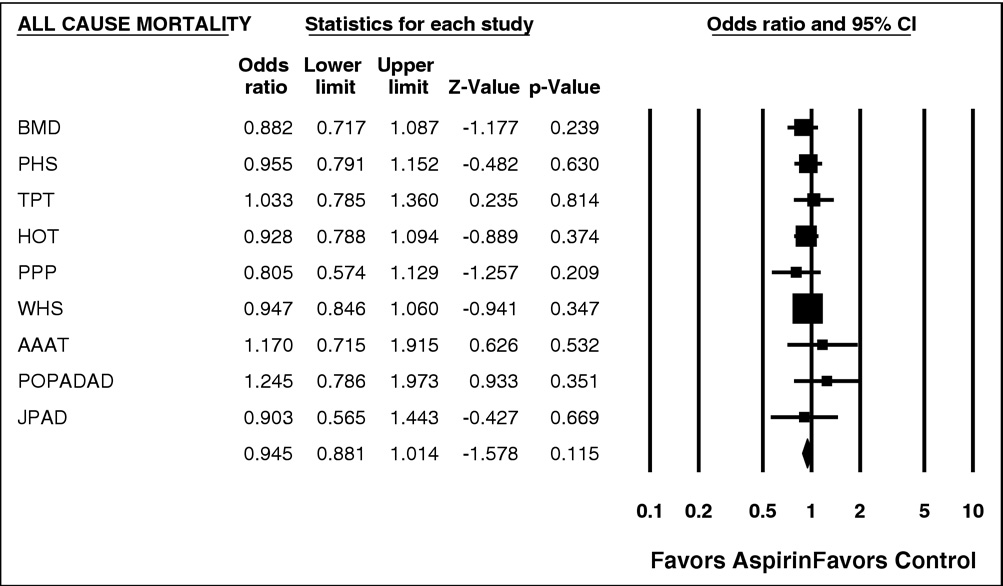

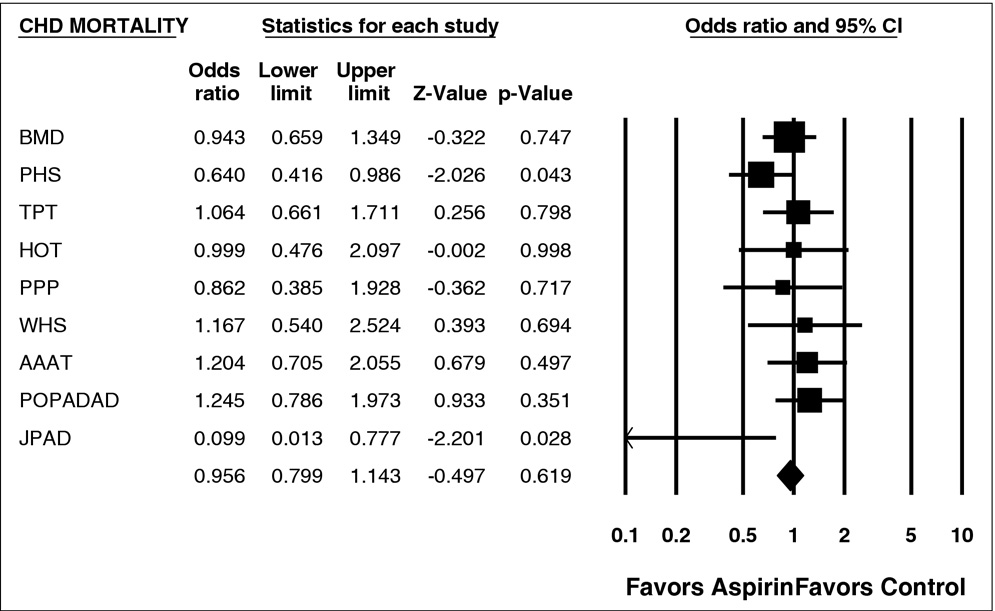

Systematic analysis of the outcomes from the 9 trials con-

have previously been diagnosed with CHD and is probably

firmed that aspirin decreases the incidence of nonfatal MI and

beneficial to all patients at high risk for developing CHD, on

CV events. However, aspirin had no statistically significant

the basis of an appropriate assessment of known risk factors.

effect on CHD, stroke, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality,

However, the 3 most recent studies on the use of aspirin in

but was highly significant for overall CV events.

primary prevention for the most part were statistically in-

In the ATTC antiplatelet therapy decreased the

Although all these studies were underpow-

combined outcome of any serious vascular event by about

ered, there was a need to reassess the use of aspirin in this

25%, nonfatal MI by about 33%, nonfatal stroke by 25%,

setting. We present a meta-analysis of all trials published to

and vascular mortality by about 16%. Our results are for the

date assessing the effect of aspirin in primary CV prevention.

most part consistent with the ATTC's results. The ATTC

Preventive Cardiology/Meta-Analysis of Aspirin in Primary Prevention

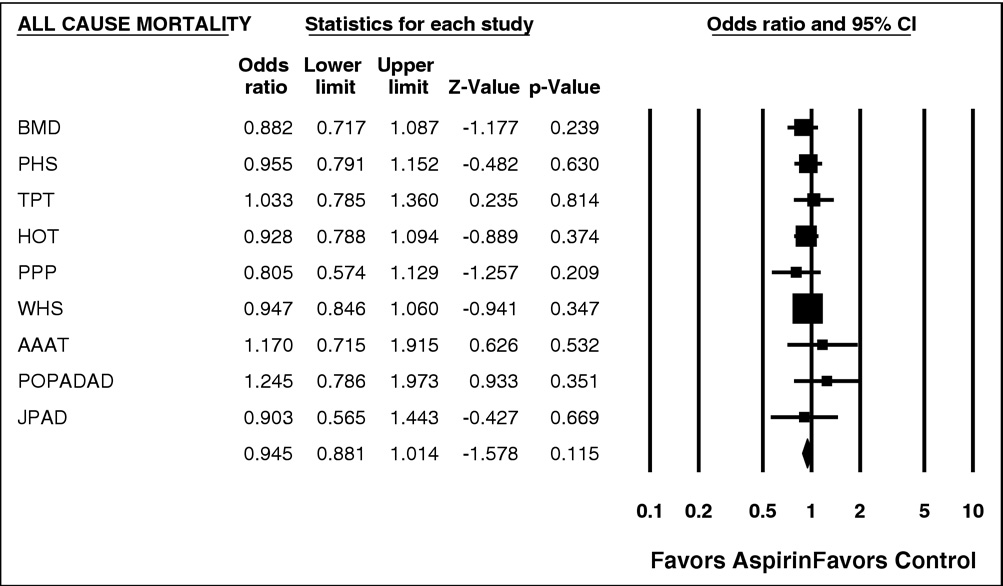

Figure 3. Forest plot of all-cause mortality. CI ⫽ confidence interval.

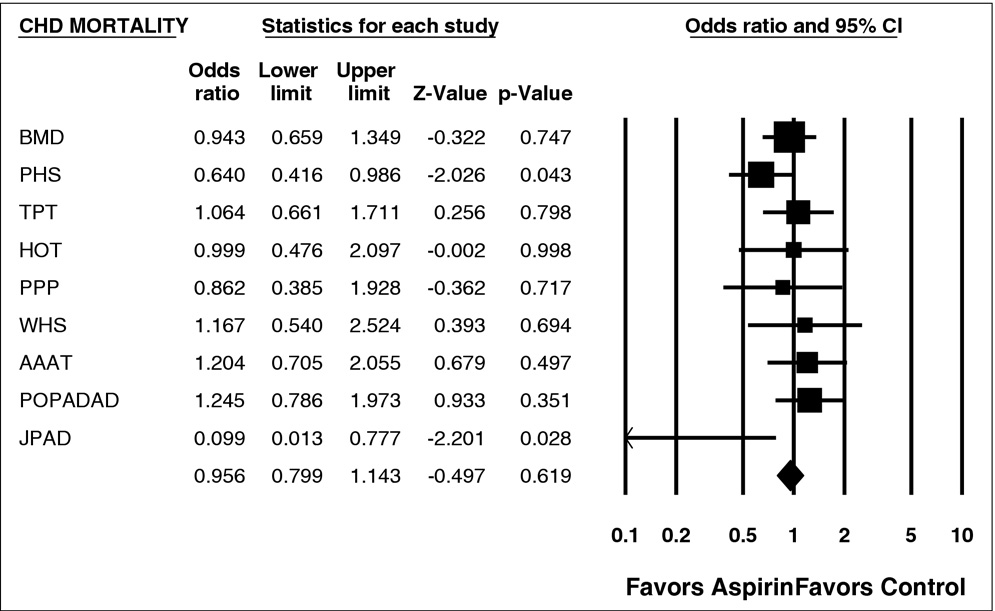

Figure 4. Forest plot of CHD mortality. CI ⫽ confidence interval.

caution that in primary prevention aspirin is of uncertain net

tained with the random-effects model, which accounts for

value, because the reduction in occlusive events needs to be

the randomness of the effects across studies.

weighed against any increase in major bleeds. Bleeds or

The HOT and WHS are relatively larger than the other

major bleeds were not our focus here, and we agree with the

studies, accounting for approximately 59% of the sample.

ATTC that gastrointestinal bleeds, strokes, and heart attacks

Thus, the meta-analysis accommodates for this difference by

may not be equivalent, as we examine these end points

assigning them greater weight (sample size) than the other

separately. See for a summary of gastrointestinal

studies. In addition, these 2 studies, when weighted accord-

bleeds across studies.

ingly in the assessment of study size bias, did not contribute

In our study, there was heterogeneity across studies for

significantly to any bias, as presented in However,

several outcomes. Possible sources of this heterogeneity

weighting can also take into account other information in

include patient selection and randomization, baseline dis-

studies, such as length of follow-up, the detail of patient char-

ease severity, management of intercurrent outcomes (such

acteristics, information on entry, and eligibility criteria. This

as bleeding, gastritis, and hypertension), and treatment strat-

information may vary across studies and, if available, will be

egies. However, the overall difference between aspirin and

scored or weighted differently in each study.

placebo, as shown in this meta-analysis, is not affected by

A limitation of our study is that it is a meta-analysis of

significant heterogeneity, because similar results were ob-

the results of published studies. Thus, we did not have the

The American Journal of Cardiology (www.ajconline.org)

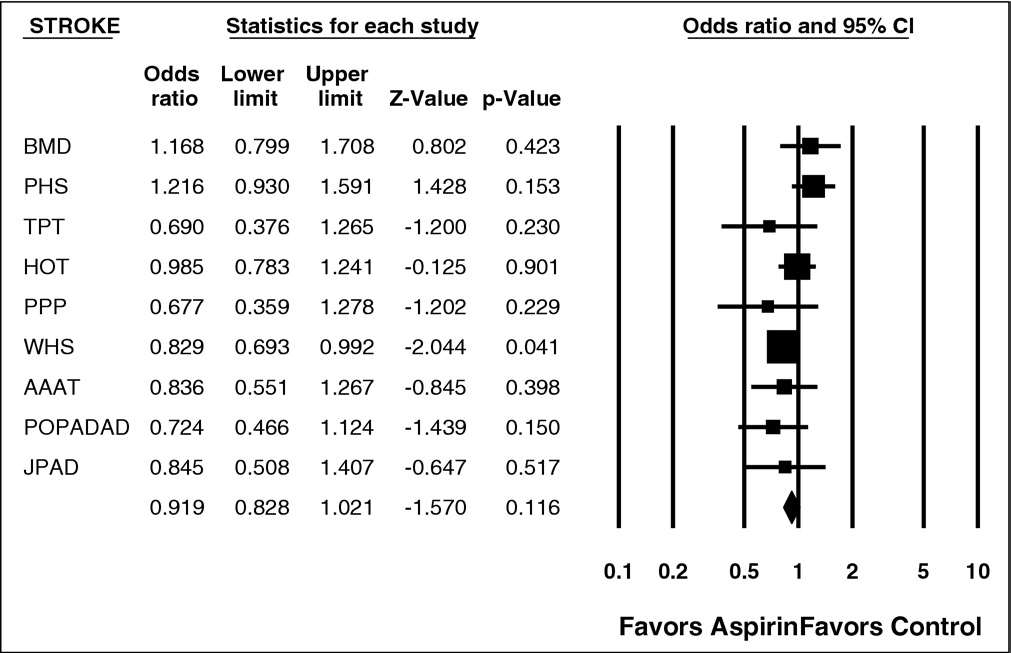

Figure 5. Forest plot of stroke events. CI ⫽ confidence interval.

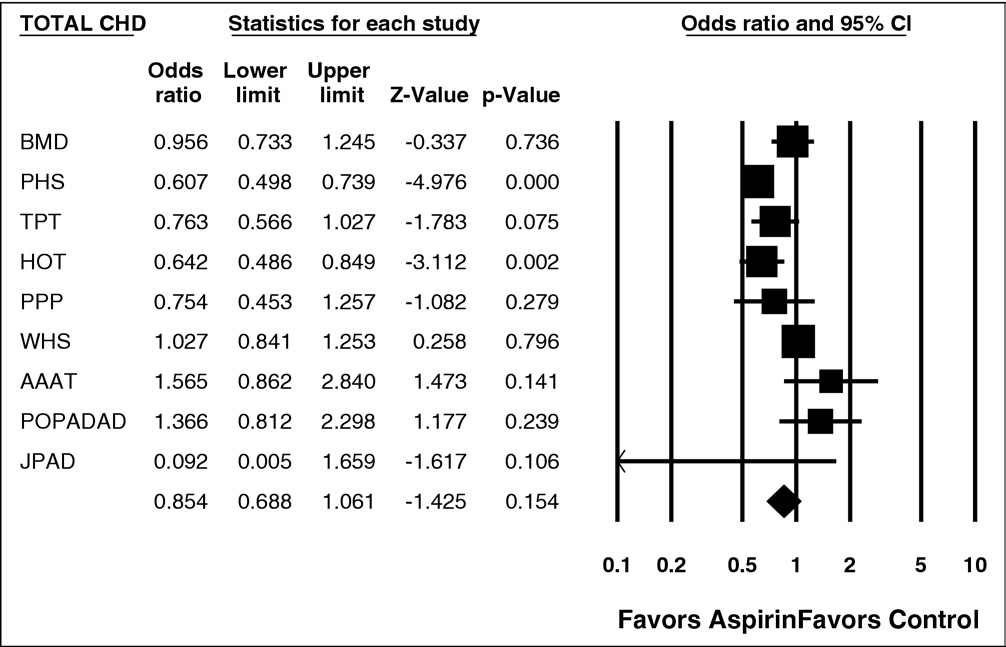

Figure 6. Forest plot of total CHD. CI ⫽ confidence interval.

ability to do thorough cross-study checks that can be done

Gastrointestinal bleeding for the 9 study meta-analysis

using the raw data. Furthermore, the overall size of oursample and the differing cohorts within each study lend

convincing evidence to the advantage of aspirin over pla-

cebo or no aspirin for decreasing the risk for CV events in

a range of patients. However, the benefits of primary pre-

vention with aspirin must be considered in relation to the

potential risks on a patient-by-patient basis.

1. Bartolucci AA, Howard G. Meta-analysis of data from the six primary

prevention trials of cardiovascular events using aspirin. Am J Cardiol

2006;98:746 –750.

Preventive Cardiology/Meta-Analysis of Aspirin in Primary Prevention

2. Fowkes FGR, Price JF, Stewart MC, Butcher I, Leng GC, Pell AC,

of individual participant data from randomized clinical trials. Lancet

Sandercock PA, Fox KA, Lowe GD, Murray GD, for the Aspirin for

Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis Trialists. Aspirin for prevention of car-

6. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the primary

diovascular events in a population screened for a low ankle brachial

prevention of cardiovascular events: recommendation and rationale.

index. JAMA 2010;303:841– 848.

Ann Intern Med 2002;136:157–160.

3. Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, Cobbe S, Taylor R, Prescott RL,

7. Egger M, Smith D, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis

Bancroft J, MacEwan S, Shepard J, Macfarlane P, Morris A, Jung R,

detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629 – 634.

Kelly C, Connacher A, Peden N, Jamieson A, Matthews D, Leese G,

8. Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Sterne J. How important are comprehen-

McKnight J, O'Brien I, Semple C, Petrie J, Gordon D, Pringle S,

sive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic

MacWalter R; Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease and Di-

reviews? Empirical study. Health Technol Assess 2003;7:1– 4.

abetes Study Group; Diabetes Registry Group; Royal College of Phy-

9. Irwig L, Macaskill P, Berry G, Glasziou P. Bias in meta-analysis

sicians Edinburgh. The Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease

detected by a simple graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ

and Diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomized placebo con-

trolled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and

10. Sterne J, Egger M, Smith D. Investigating and dealing with publication

asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2008;337:a1840.

and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ 2001;323:101–105.

4. Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, Uemura S, Kanauchi M, Doi N,

11. Macaskill P, Walter S, Irwig L. A comparison of methods to detect

Jinnouchi H, Sugiyama S, Saito Y, for the Japanese Primary Preven-

publication bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2001;20:641– 654.

tion of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) Trial Inves-

12. Schwarzer G, Antes G, Shumacher M. Inflation of type I error rate in

tigators. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic

two statistical tests for the detection of publication bias in metaanalysis

events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial.

with binary outcomes. Stat Med 2002;21:2465–2477.

JAMA 2008;300:2134 –2141.

13. Harbord R, Egger M, Sterne J. A modified test for small study effects

5. Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and

in meta-analysis of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med

secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis

Source: http://jacemedical.com/articles/Aspirin%20does%20not%20decrease%20deaths%20from%20heart%20attacks%20or%20all-cause%20mortality.pdf

New Release Dana Pickel Dana Pickel GYMINI® Sunny Day GYMINI® Belle journée GYMINI® Zonnige Dag GYMINI® Día de Sol GYMINI® Dia Ensolarado Guía de instrucciones PLEASE KEEP THIS INSTRUCTION GUIDE AS IT CONTAINS IMPORTANT INFORMATION. READ CAREFULLY.

The Neurobehavioral Pharmacology of Ketamine: Implications for Drug Abuse, Addiction, and Psychiatric Disorders Keith A. Trujillo, Monique L. Smith, Brian Sullivan, Colleen Y. Heller, Cynthia Garcia, and Melvin Bates Ketamine was initially developed in the 1960s as a safer alternative to phencyclidine (PCP1) for anes- Ketamine was developed in the early 1960s as an anesthetic