Niph.org.kh

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

UNAIDS/WHO guidance document

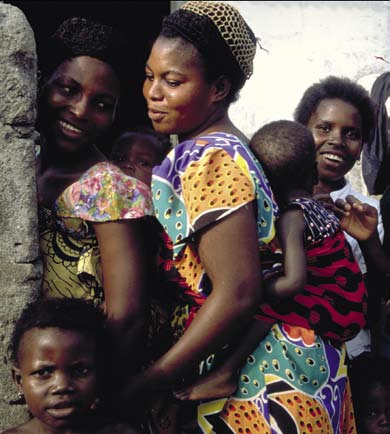

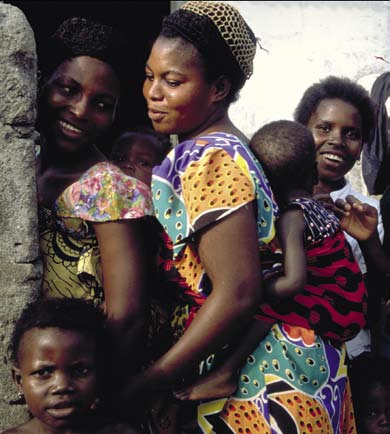

Cover photos: L Taylor/UNAIDS, S Noorani/UNAIDS

UNAIDS/07.28E / JC1349E (English original, July 2007)

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)

2007. All rights reserved.

The designations employed and the presentation of the

material in this publication do not imply the expression of

any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning

the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of

its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers

UNAIDS does not warrant that the information contained

in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use.

WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials.

«UNAIDS/07.28E / JC1349».

1.HIV infections - prevention and control. 2.Bioethics.

3.Biomedical research. 4.Intervention studies. I.UNAIDS.

II.World Health Organization.

ISBN 978 92 9 173625 6 (NLM classification: WC 503.6)

UNAIDS – 20 avenue Appia – 1211 Geneva 27 – SwitzerlandTelephone: (+41) 22 791 36 66 – Fax: (+41) 22 791 48 35E-mail: [email protected] – Internet: http://www.unaids.org

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

UNAIDS and WHO gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the Expert Panel which proposed changes to the 2000 UNAIDS guidance document "Ethical considerations in HIV preventive vaccine trials". Members of the Expert Panel met in Montreux, Switzerland at a consultation chaired by Catherine Hankins (UNAIDS Secretariat) to review the entire document, discuss each guidance point and come to consensus on suggested wording.

Expert Panel Members:

Quarraisha Abdool Karim*, Women and HIV/AIDS Programme University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa

Jorge Beloqui*, Grupo de Incentivo à Vida, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Alexander M. Capron, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, United States of America

Dirceu Greco, Professor, Internal Medicine, Coordinator of the Center of Clinical Research, University Hospital and School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Lori Heise*, Global Campaign for Microbicides, Washington DC, United States of America

Ruth Macklin, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, United States of America

Sheena McCormack, Microbicides Development Programme, Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit, London, United Kingdom

Kathleen MacQueen, Family Health International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, United States of America

Vasantha Muthuswamy*, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India

Punnee Pitisuttithum, Professor for Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Carmel Shalev, Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Cathy Slack, HIV/AIDS Vaccine Ethics Group (HAVEG), University of Natal, Durban, South Africa

Daniel Tarantola, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Morenike Ukpong, Nigeria HIV Vaccines and Microbicide Advocacy Group, Nigeria

Steve Wakefield, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, Seattle, United States of America

Mitchell Warren*, AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, New York, United States of America

Oversight to the process revising the guidance document was provided by a UNAIDS/WHO Working Group composed of the following members:

Catherine Hankins, UNAIDS Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland (chair)

Saladin Osmanov, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Zarifah Reed, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Jason Sigurdson, UNAIDS Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland

Marie-Charlotte Bouesseau*, World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland

Yves Souteyrand*, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Tatiana Lemay*, UNAIDS Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland

Jolene Nakao, UNAIDS Secretariat, Geneva Switzerland

UNAIDS and WHO would also like to express their sincere appreciation to Carmel Shalev who prepared the draft for the Expert Panel by incorporating content and recommendations from meetings and consultations conducted on topics related to the ethical conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials as well as related literature since 2000.

Catherine Hankins, Carmel Shalev and Jolene Nakao finalized revisions after the Montreux meeting. Mihika Acharya and Constance Kponvi assisted with editing and Lon Rahn did the layout.

A companion document which readers may wish to consult is the UNAIDS/AVAC Good Participatory Practice for Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials. It covers core principles and essential activities throughout the research life-cycle, providing a foundation for community engagement in research. It is available on the UNAIDS website in a number of languages. For more information please contact [email protected] .

Comments on the Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials and experience with implementation of this guidance are welcome. Please send them to [email protected]

* Those who did not attend the Montreux meeting

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

SUGGESTED GUIDANCE

Guidance Point 1: Development of Biomedical HIV Prevention Interventions 15

Guidance Point 2: Community Participation

Guidance Point 3: Capacity Building

Guidance Point 4: Scientific and Ethical Review

Guidance Point 5: Clinical Trial Phases

Guidance Point 6: Research Protocols and Study Populations

Guidance Point 7: Recruitment of Participants

Guidance Point 8: Vulnerable Populations

Guidance Point 9: Women

Guidance Point 10: Children and Adolescents

Guidance Point 11: Potential Harms

Guidance Point 12: Benefits

Guidance Point 13: Standard of Prevention

Guidance Point 14: Care and Treatment

Guidance Point 15: Control Groups

Guidance Point 16: Informed Consent

Guidance Point 17: Monitoring Informed Consent and Interventions

Guidance Point 18: Confidentiality

Guidance Point 19: Availability of Outcomes

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Guidance Point 1: Development of Biomedical HIV Prevention Interventions

Given the human, public health, social, and economic severity of the HIV epidemic, countries, development partners, and relevant international organisations should promote the establishment and strengthening of sufficient capacity and incentives to foster the early and ethical development of additional safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention methods, both from the point of view of countries and communities in which biomedical HIV prevention trials take place, and from the point of view of trial sponsors and researchers.

Guidance Point 2: Community Participation

To ensure the ethical and scientific quality and outcome of proposed research, its relevance to the affected community, and its acceptance by the affected community, researchers and trial sponsors should consult communities through a transparent and meaningful participatory process which involves them in an early and sustained manner in the design, development, implementation, monitoring, and distribution of results of biomedical HIV prevention trials.

Guidance Point 3: Capacity Building

Development partners and relevant international organisations should collaborate with and support countries in strategies to enhance capacity so that countries and communities in which trials are being considered can practice meaningful self-determination in decisions about the scientific and ethical conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials and can function as equal partners with trial sponsors, local and external researchers, and others in a collaborative process.

Guidance Point 4: Scientific and Ethical Review

Researchers and trial sponsors should carry out biomedical HIV prevention trials only in countries and communities that have appropriate capacity to conduct independent and competent scientific and ethical review.

Guidance Point 5: Clinical Trial Phases

As phases I, II, and III in the clinical development of a biomedical HIV preventive intervention all have their own particular scientific requirements and specific ethical challenges, researchers and trial sponsors should justify in advance the choice of study populations for each trial phase, in scientific and ethical terms in all cases, regardless of where the study population is found. Generally, early clinical phases of biomedical HIV prevention research should be conducted in communities that are less vulnerable to harm or

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

exploitation, usually within the sponsor country. However, countries may choose, for valid scientific and public health reasons, to conduct any trial phase within their populations, if they are able to ensure sufficient scientific infrastructure and sufficient ethical safeguards.

Guidance Point 6: Research Protocols and Study Populations

In order to conduct biomedical HIV prevention trials in an ethically acceptable manner, researchers and relevant oversight entities should ensure that the research protocol is scientifically appropriate and that the interventions used in the experimental and control arms are ethically justifiable.

Guidance Point 7: Recruitment of Participants.

In order to conduct biomedical HIV prevention trials in an ethically acceptable manner, participation of individuals should be voluntary and the selection of participating communities and individuals must be fair and justified in terms of the scientific goals of the research.

Guidance Point 8: Vulnerable Populations

The research protocol should describe the social contexts of a proposed research population (country or community) that create conditions for possible exploitation or increased vulnerability among potential trial participants, as well as the steps that will be taken to overcome these and protect the rights, the dignity, the safety, and the welfare of the participants.

Guidance Point 9: Women

Researchers and trial sponsors should recruit women into clinical trials in order to verify safety and efficacy from their standpoint, including immunogenicity in the case of vaccine trials, since women throughout the life span, including those who may become pregnant, be pregnant or be breastfeeding, should be recipients of future safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention interventions. During such research, women should receive adequate information to make informed choices about risks to themselves, as well as to their foetus or breastfed infant, where applicable.

Guidance Point 10: Children and Adolescents

Children and adolescents should be included in clinical trials in order to verify safety and efficacy from their standpoint, in addition to immunogenicity in the case of vaccines, since they should be recipients of future biomedical HIV preventive interventions. Researchers, trial sponsors, and countries should make efforts to design and implement biomedical HIV prevention product development programmes that address the particular safety, ethical, and legal

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

considerations relevant for children and adolescents, and safeguard their rights and welfare during participation.

Guidance Point 11: Potential Harms

Research protocols should specify, as fully as reasonably possible, the nature, magnitude, and probability of all potential harms resulting from participation in a biomedical HIV prevention trial, as well as the modalities by which to minimise the harms and mitigate or remedy them.

Guidance Point 12: Benefits

The research protocol should provide an accurate statement of the anticipated benefit of the procedures and interventions required for the scientific conduct of the trial. In addition, the protocol should outline any services, products, and other ancillary interventions provided in the course of the research that are likely to be beneficial to persons participating in the trials.

Guidance Point 13: Standard of Prevention

Researchers, research staff, and trial sponsors should ensure, as an integral component of the research protocol, that appropriate counselling and access to all state of the art HIV risk reduction methods are provided to participants throughout the duration of the biomedical HIV prevention trial. New HIV-risk-reduction methods should be added, based on consultation among all research stakeholders including the community, as they are scientifically validated or as they are approved by relevant authorities.

Guidance Point 14: Care and Treatment

Participants who acquire HIV infection during the conduct of a biomedical HIV prevention trial should be provided access to treatment regimens from among those internationally recognised as optimal. Prior to initiation of a trial, all research stakeholders should come to agreement through participatory processes on mechanisms to provide and sustain such HIV-related care and treatment.

Guidance Point 15: Control Groups

Participants in both the control arm and the intervention arm should receive all established effective HIV risk reduction measures. The use of a placebo control arm is ethically acceptable in a biomedical HIV prevention trial only

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

when there is no HIV prevention modality of the type being studied that has been shown to be effective in comparable populations.

Guidance Point 16: Informed Consent

Each volunteer being screened for eligibility for participation in a biomedical HIV prevention trial should provide voluntary informed consent based on complete, accurate, and appropriately conveyed and understood information before s/he is actually enrolled in the trial. Researchers and research staff should take efforts to ensure throughout the trial that participants continue to understand and to participate freely as the trial progresses. Informed consent, with pre- and post-test counselling, should also be obtained for any testing for HIV status conducted before, during, and after the trial.

Guidance Point 17: Monitoring Informed Consent and Interventions

Before a trial commences, researchers, trial sponsors, countries, and communities should agree on a plan for monitoring the initial and continuing adequacy of the informed consent process and risk-reduction interventions, including counselling and access to proven HIV risk-reduction methods.

Guidance Point 18: Confidentiality

Researchers and research staff must ensure full respect for the entitlement of potential and enrolled participants to confidentiality of information disclosed or discovered in the recruitment and informed consent processes, and during conduct of the trial. Researchers have an ongoing obligation to participants to develop and implement procedures to maintain the confidentiality and security of information collected.

Guidance Point 19: Availability of Outcomes

During the initial stages of development of a biomedical HIV prevention trial, trial sponsors and countries should agree on responsibilities and plans to make available as soon as possible any biomedical HIV preventive intervention demonstrated to be safe and effective, along with other knowledge and benefits helping to strengthen HIV prevention, to all participants in the trials in which it was tested, as well as to other populations at higher risk of HIV exposure in the country, potentially by transfer of technology.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Well into the third decade of the HIV pandemic, there remains no effective HIV preventive vaccine, microbicide, product or drug to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition. As the numbers of those infected by HIV and dying from AIDS continue to increase, the need for such biomedical HIV preventive interventions becomes ever more urgent. Several such products are at various stages of development, including some currently in phase III efficacy trials. The successful development of effective HIV preventive interven-tions requires that many different candidates be studied simultane-ously in different populations around the world. This in turn will require a large international cooperative effort drawing on partners from various health sectors, inter-governmental organisations, government, research institutions, industry, and affected populations. It will also require that these partners be able and willing to address the difficult ethical concerns that arise during the development of biomedical HIV prevention products.

Following deliberations during 1997-99 involving lawyers, activists, social scientists, ethicists, vaccine scientists, epidemiologists, non-governmental organisation (NGO) representatives, people living with HIV, and people working in health policy from a total of 33 countries, UNAIDS published a guidance document on ethical considerations in HIV preventive vaccine research in 2000. Since then there have been numerous developments related to the conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials, including vaccine trials. Consultations have been held to explore key issues such as:

Creating effective partnerships, collaboration and community

participation in HIV prevention trials (International AIDS Society

(IAS) 2005; UNAIDS 2006; UNAIDS/AIDS Vaccine Advocacy

Coalition (AVAC) 2007);

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

The inclusion of adolescents in HIV vaccine trials (WHO/IVR

2002; WHO/UNAIDS 2004; WHO/UNAIDS/African AIDS

Vaccine Program 2006);

Gender considerations related to enrolment and informed consent

(WHO/UNAIDS 2004);

Provision of support, care and treatment to participants and the

community engaged in HIV prevention trials (WHO/UNAIDS

2003; IAS 2005; UNAIDS 2006; Forum for Collaborative

Research 2006; International AIDS Society Industry Liaison

Post-trial responsibilities of sponsors, researchers and local

providers (AVAC and the International Council of AIDS Service

In light of these consultations, and evolution in the level of prevention, treatment and care available in the era of ‘Towards Universal Access', the 2000 guidance document was revised and updated. The revision incorporates developments which have taken place since the original publication, including lessons learned in the field of biomedical HIV prevention research. Many different strategies for HIV prevention are now being explored, including microbicides, vaccines, female-initiated barrier methods, herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) treatment/suppres-sion, index partner treatment, antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis, prevention of mother-to-child transmission and drug substitution/maintenance for injecting drug users. Of note, following the compel-ling evidence of a 50 to 60 per cent reduction in HIV acquisition for men who became circumcised in three randomised controlled trials in South Africa, Kenya and Uganda, WHO/UNAIDS produced recommendations in 2007 judging adult male circumcision to be an accepted risk reduction measure in men, particularly in high preva-lence generalised HIV epidemics in which heterosexual transmis-sion predominates. Finally, the guidelines in this document specifi-cally address trials of biomedical HIV preventive interventions but are relevant to those engaged in trials of various behavioural HIV prevention methods.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

This document does not purport to capture the extensive discussion, debate, consensus, and disagreement which have taken place among stakeholders in HIV prevention research. Rather it highlights, from the perspective of UNAIDS and WHO, some of the critical ethical elements that must be considered during the development of safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention interventions. Where these are adequately addressed, in the view of UNAIDS/WHO, by other existing texts, there is no attempt to duplicate or replace these texts, which should be consulted extensively throughout biomedical HIV prevention product development activities. Such texts include: the Nuremberg Code (1947); the Declaration of Helsinki, first adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964 and most recently amended in 2000 ; the revised International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, issued in 2002 by the Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) (and developed in close cooperation with WHO); the World Health Organization's Handbook for Good Clinical Research Practice (2005); the International Conference on Harmonisation's Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP) Guideline (1996); and the UNAIDS Interim Guidelines on Protecting the Confidentiality and Security of HIV Information (2007).

Systematic guidance on the role and responsibilities of entities funding and conducting biomedical HIV prevention trials towards participants, and their communities can be found in the UNAIDS/AVAC Good Participatory Practice Guidelines for Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials (2007).

It is hoped that this document will be of use to potential research volunteers and trial participants, investigators, research staff, community members, government representatives, pharmaceutical companies and other industry partners and trial sponsors, and ethical and scientific review committees involved in the development of biomedical HIV prevention products and interventions. It suggests standards, as well as processes for arriving at standards which can be used as a frame of reference from which to conduct further discussion at the local, national, and international levels and can inform the development of national guidelines for the conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

The HIV pandemic is characterised by unique biological, social and geographical factors that, among other things, affect the balance of risks and benefits for individuals and communities who participate in biomedical HIV prevention trials. These factors may require that additional efforts be taken to address the needs of participating indi-viduals and communities. They have an urgent need for additional HIV prevention choices for use at various stages of the life-cycle, a need to have their rights protected and their welfare promoted in the context of the development and testing of novel HIV prevention modalities, and a need to be able to participate fully as equal partici-pants in the research process. These factors include the following:

The global burden of disease and death related to HIV continues

to increase at a rate unmatched by any other pathogen. For many countries, AIDS is the leading cause of death. Currently available treatments do not lead to cure, but do slow the progression of disease. The most effective treatment for slowing HIV-related disease progression, antiretroviral medication, is a life-long treatment which requires close medical monitoring, is still very costly, especially for 2nd line regimens, and can cause significant adverse effects. Because of this, antiretroviral medi-cation is not readily available to the vast majority of people living with HIV who need it. More than 2 million people had access to antiretroviral treatments in low- and middle-income countries in 2006, five times more people than in 2003. But despite this tremendous progress in the roll-out of antiretroviral treatment, global coverage of needs is below 30%.

For every person placed on antiretroviral treatment in 2006,

another six people became newly infected with HIV. There is therefore an ethical imperative to seek, as urgently as possible, effective and accessible biomedical HIV prevention technolo-gies, to complement existing prevention strategies. This ethical

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

imperative demands that these technologies be developed to address the situation of those people and populations most vulnerable to exposure to HIV infection.

Genetically distinct subtypes of HIV have been described, and

different HIV subtypes are predominant in different regions and countries. The relevance of these sub-types to probabilities of HIV transmission and acquisition, speed of disease progression and potential protection is not clearly understood.

For the conduct of efficacy trials of any biomedical HIV

prevention product, the populations with the highest incidence of HIV will be those most likely to be considered for participa-tion and would be those most likely to benefit from an effective intervention. However, for a variety of reasons, these popula-tions may be relatively vulnerable to exploitation and harm in the context of biomedical HIV prevention trials. Trial sponsors, countries, researchers, research staff and community leaders must make additional efforts to overcome this vulnerability.

In some biomedical HIV prevention trials, individuals other than

the trial participants may experience risks if they are exposed to the experimental product and may experience benefits if the product is effective. For example in trials of prophylaxis of mother-to-child transmission, the foetus is exposed to the prophylactic antiretroviral regimen in addition to the mother. If the mother develops antiretroviral resistance, she may transmit resistant virus to the infant. When the intervention is effective, the newborn baby is protected. In trials of vaginal microbicides, male sexual partners may be exposed to the product even when condoms are used. In trials of successful vaccine candidates, not only sexual partners benefit but communities may benefit from population level effects.

Some biomedical HIV prevention modalities may be conceived

and manufactured in laboratories of one country (sponsor country or countries), usually in high-income countries, and tested in human populations in another country, often low- and middle-income countries. The potential imbalance of such a

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

situation demands particular attention to ways to address the differing perspectives, interests and capacities of trial sponsors, countries, and communities engaged in trials with the goal of encouraging the urgent development of additional safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention tools, in ethically accept-able manners, and their early distribution to populations most in need. Countries and communities considering participa-tion in biomedical HIV prevention trials should be encour-aged and given the capacity to make decisions for themselves regarding their participation, based on their own health and human development priorities, in a context of equal collabora-tion with sponsors.

HIV infection is both highly feared and stigmatised. This is in

large part because it is associated with blood, death, sex, and activities which may not be legally sanctioned, such as commer-cial sex, men having sex with men, and illicit substance use. These are issues which are often difficult to address openly - at a societal and individual level. As a result, people living with HIV and those affected by AIDS may experience stigma, discrimination, and even violence; some communities continue to deny the existence and prevalence of HIV infection. Furthermore, vulnerability to HIV exposure and to the impact of AIDS is greater where people are marginalized due to their social, economic, and legal status. These factors increase the risk of social and psychological harm for people participating in biomedical HIV prevention trials. Additional efforts must be made to address these increased risks and to ensure that the risks participants take are justified by the anticipated benefits of the preventive intervention to the participants themselves or to others in the future.

A key means by which to protect participants and the commu-

nities from which they come is to ensure that the community in which the research is carried out is meaningfully involved in the design, implementation, monitoring, and dissemination of results of HIV prevention trials, including the involvement of representatives from marginalized communities from which participants are drawn.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Site selection for moving forward into empirical efficacy

trials of biomedical HIV prevention technologies is a major challenge. Part of this challenge is the need to integrate biomedical HIV prevention tool development with other HIV prevention modalities, all of which need to be integrated with HIV treatment and care as provided by the local health care system. It is imperative that appropriate financial arrangements are in place to implement agreements made between partners at the time a study is initiated. These agreements should cover the period of the trial but also address what will be provided to study participants once the study is completed. Advance planning and collaboration between partners is also needed to facilitate timely product licensure and distribution once a method has been proven safe and effective.

It has been the experience to date that HIV incidence in both

the experimental and control arms of biomedical HIV preven-

tion trials tends to fall below the pre-trial incidence, presumably

as a result of sustained risk-reduction counselling and provision

of effective HIV prevention tools. The discovery of additional

safe and effective biomedical HIV preventive interventions will

necessitate discussions among all research stakeholders involved in

planned or active trials of other biomedical HIV prevention tools.

A decision to introduce the new method in a trial that is already

underway has to be made collectively as it may have implications

for resource requirements, sample sizes, and potential futility of

continuing the trial. The possibility that such a decision could be

required should be anticipated during initial discussions among

the research stakeholders.

No single biomedical HIV prevention product or intervention is

now or will be 100 per cent effective. This is in part because none

are expected to achieve 100 per cent efficacy in the controlled

circumstances of a trial and in part because behaviour will

influence both consistency and correctness of uptake for many

of the interventions being investigated, with the result that the

efficacy seen in the trial will not lead to effectiveness at the same

level in the real world. Furthermore, the manner in which an

effective biomedical HIV prevention product is introduced into

comprehensive HIV prevention programming will affect the

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

extent to which risk compensation1 will occur. Therefore, social

change communication strategies which emphasize combination

prevention will be crucial to ensure that a new biomedical HIV

prevention product truly does add to the existing tools when it is

Selected circumstances in which biomedical

HIV prevention trials should not be conducted

when the product to be tested would not be appropriate for

use, should it be proven safe and effective, in the community

that would participate in the trial (see Guidance Point 1);

when capacity to conduct independent and competent scien-

tific and ethical review does not exist (see Guidance Point 4);

where truly voluntary participation and ongoing free informed

consent cannot be obtained (see Guidance Point 7);

when conditions affecting potential vulnerability or exploita-

tion may be so severe that the risk outweighs the benefit of

conducting the trial in that population (see Guidance Point 8);

when a survey of protective local laws and regulations applicable

at the trial site has not been conducted or when such a survey

indicates insurmountable legal barriers (see Guidance Point 10);

when agreements have not been reached among all research

stakeholders on standard of prevention (see Guidance Point 13)

and access to care and treatment (see Guidance Point 14);

when agreements have not been arrived at on responsibili-

ties and plans to make a trial product which proves safe and

effective affordably available to communities and countries

where it has been tested (see Guidance Point 19).

� Risk compensation: an increase in risk-taking as a result of a decrease in perception

� The term "combination prevention" refers to the combination of various strategies

that individuals can choose at different times in their lives to reduce their risks of

sexual exposure to the virus.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

SUGGESTED GUIDANCE

Guidance Point 1:

Development of Biomedical HIV Prevention Interventions

Given the human, public health, social, and economic severity of the HIV epidemic, countries, development partners, and relevant international organisations should promote the establishment and strengthening of sufficient capacity and incentives to foster the early and ethical development of additional safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention methods, both from the point of view of countries and communities in which biomedical HIV prevention trials take place, and from the point of view of trial sponsors and researchers.

Given the global nature of the epidemic, the devastation being wrought in some countries by it, the fact that biomedical HIV preventive interventions may be the best long term solution by which to control the epidemic, especially in low- and middle-income countries, and the potentially universal benefits of effective biomedical HIV prevention tools, there is an ethical imperative for global support to develop these modalities. This effort requires intense international collaboration and coordination over time among countries with scientific expertise and resources, and countries in which candidate products could be tested but whose infrastructure, resource base, and scientific and ethical capacities may need strengthening. Though potential HIV prevention tools such as microbicides, vaccines, herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) suppression/treatment, female-initiated barrier methods, index partner treatment, antiretroviral drugs for prophylaxis, and biomedical interventions for injecting drug users should benefit all those in need, it is imperative that they benefit the populations at greatest risk of exposure to HIV. Thus, HIV prevention

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

product development should ensure that products are appropriate for use among such populations, among which it will be necessary to conduct trials; and, when developed, they should be made available and affordable to such populations.

Because HIV prevention product development activities take time, are complex, and require infrastructure, resources, and international collaboration,

countries who may sponsor trials and countries who may

participate in trials should include biomedical HIV prevention

product development in their national HIV prevention and

control plans.

countries who may participate in trials should assess how they

can and should take part in biomedical HIV prevention product

development activities either nationally or on a regional basis,

including identifying resources, establishing partnerships,

conducting national information and research literacy campaigns,

strengthening their scientific and ethical sectors, and including

biomedical HIV prevention product research to complement

current comprehensive HIV prevention programming.

development partners, international agencies, and governments

should make early and sustained commitments to allocate sufficient

funds to make biomedical HIV preventive interventions a reality.

This includes funds to strengthen ethical and scientific capacity

in countries where multiple trials will have to be conducted, to

enhance South-South as well as North-South capacity building

and technology transfer, and to purchase and distribute future

biomedical HIV prevention tools.

potential trial sponsors and countries who may participate in

trials should establish partnerships with each other, initiate

community consultations, support the strengthening of

necessary scientific and ethical components, and make plans

with all stakeholders for equitable distribution of the benefits of

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Guidance Point 2:

Community Participation2

To ensure the ethical and scientific quality and outcome of proposed research, its relevance to the affected community, and its acceptance by the affected community, researchers and trial sponsors should consult communities through a transparent and meaningful participatory process which involves them in an early and sustained manner in the design, development, implementation, and distribution of results of biomedical HIV prevention trials.

It is highly important to engage in consultations with communities who will participate in the trial from the beginning of the research concept, in an open, iterative, collaborative process that involves a wide variety of participants and takes place under public scrutiny. Participatory management benefits all parties; helps ensure smooth trial functioning; and builds community capacity to understand and inform the research process, raise concerns, and help find solutions to unexpected issues that may emerge once the trial is underway. Failure to properly and genuinely engage communities early in the stages of research planning may result in an inability to properly conduct and complete important trials. Furthermore, active community participation should strengthen not only local ownership of the research, but also the negotiating power of communities, the research skills of local investigators, and the social leverage that can be useful in areas of the society beyond the research trial site. Communities of people affected by research should conversely play an active, informed role in all aspects of its planning and conduct, as well as the dissemination of results. Achieving meaningful participation requires

� Consider further the UNAIDS/AVAC Good Participatory Practice Guidelines for

Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials (�007).

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

the acknowledgement of structural power imbalances between certain communities and researchers and/or research sponsors, and striving to overcome them. In practical terms, this means putting in place outreach and engagement measures to support participation. Special attention should be paid to the inclusion and empowerment of women for active involvement throughout the research process, as well as to the representation of populations at higher risk of HIV exposure, including adolescents.

The nature of community involvement should be one of continuous

mutual education and respect, partnership, and consensus-building

regarding all aspects of the testing of potential biomedical HIV

prevention products. A continuing forum should be established for

communication and problem-solving on all aspects of the HIV

prevention product development programme from phase I through

phase III and beyond (see Guidance Point 6), to the distribution of a safe

and effective HIV prevention tool. All participating parties should define

the nature of this ongoing relationship. It should include appropriate

representation from the community on committees charged with the

review, approval, and monitoring of a biomedical HIV prevention trial.

As with investigators and sponsors, communities should also assume

appropriate responsibility to assure the successful completion of the

trial and the product development programme.

Defining the relevant community for consultation and partnership is a complex and evolving process that should be discussed with relevant local authorities. As more groups and people define themselves as part of the interested community, the concept needs to be broadened to civil society so as to include advocates, media, human rights organizations, national institutions and governments, as wel as researchers and community representatives from the trial site. Partnership agreements should include a clear delineation of roles for al stakeholders and should specify the responsibilities of sponsors, governments, community, advocacy organiza-tions, and media, as wel as researchers and research staff.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Appropriate community representatives should be determined through a process of broad consultation. An agreement should be reached among stakeholders about the definition of a "community" and ways that it can be effectively represented in decision-making early in the design of the study protocol. The process for determining who will be credible and legitimate community representatives should be addressed through a preliminary consultative process between researchers and key members of the community in which the research is proposed to take place. Members of the community who may contribute to development of a safe and effective HIV prevention product include representatives of the research population eligible to serve as research participants, other members of the community who would be among the intended beneficiaries of the developed product, relevant non-government organisations, persons living with HIV, community leaders, public health officials, and those who provide health care and other services to people living with and affected by HIV.

Formal community meetings need to be organised in a way that facili-tates the active participation of those most affected by the research being proposed. The principal investigator and site research staff should work with representatives of affected communities to identify needs related to their participation, including logistical requirements such as trans-portation to the meeting site. Educational materials should be designed in an accessible format, using easy to understand language. Adequate consultation and full participation in the planning process will require more than formal community meetings, as such meetings may alienate some people or be inaccessible to others due to the timing or the format. The principal investigator and site research staff should make efforts to reach out to affected communities, meeting at community centres, workplaces, and other frequented locations. In both formal and informal consultations, the timing and length of the meetings should be convenient for community members, using approaches that facilitate two-way communication with two goals in mind: (1) to identify and

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

understand community concerns and needs, as well as their knowledge and experience, and (2) to clearly describe the research being proposed, related benefits and risks, and other practical implications.

Participation of the community in the planning and implementation of a biomedical HIV prevention product development strategy can provide at least these favourable consequences:

information regarding the health beliefs and understanding of the

information regarding the cultural norms and practices of the

input into the design of the protocol input into the design of an effective recruitment and informed

insight into the design of risk reduction interventions effective methods for disseminating information about the trial

information to the community-at-large on the proposed research trust between the community and researchers equity in eligibility criteria for participation equity in decisions regarding level of care and treatment and its

equity in plans for releasing results and distributing safe and effi-

cacious HIV prevention products.

Researchers may lack the requisite language, communication skills, and experience to respond to community concerns, while communi-ties may be unfamiliar with research concepts, such as "double blind" and "cause and effect", and may not define HIV prevention research as a priority. This underscores the need for "joint literacy", whereby researchers and community groups become sufficiently fluent in the requisite concepts and language to work productively together. Research literacy programs that include ethics training for study staff can facilitate and enhance cooperation with civil society groups.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Guidance Point 3:

Capacity Building

Development partners and relevant international organisations should collaborate with and support countries in strategies to enhance capacity so that countries and communities in which trials are being considered can practice meaningful self-determination in decisions about the scientific and ethical conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials and can function as equal partners with trial sponsors, local and external researchers, and others in a collaborative process.

Countries and communities who choose to participate in biomedical HIV prevention trials have the right, and the responsibility, to make decisions regarding the nature of their participation. Yet disparities in economic wealth, scientific experience, and technical capacity among countries and communities have raised concern about possible exploitation of participant countries and communities. The develop-ment and testing of biomedical HIV preventive interventions requires international cooperative research, which should transcend, in an ethical manner, such disparities. Real or perceived disparities should be resolved in a way that ensures equality in decision-making and action. The desired relationship is one of equals, whose common aim is to develop a long-term partnership through South-South as well as North-South collaboration that sustains site research capacity.

Factors that affect perceptions of disparity in power between sponsors and the countries and communities in which research takes place may include, but are not limited to, the following:

level of the proposed community's economic capacity and social

community/cultural experience with and/or understanding of

scientific research and of their responsibilities;

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

research staff experience with and/or understanding of the

local political awareness of the importance and process of biomed-

ical HIV prevention trials;

local infrastructure, personnel, and technical capacity for providing

comprehensive HIV health care and treatment options;

ability of individuals in the community to freely provide informed

consent, in light of cultural norms, socio-economic status, gender,

and other social factors (see Guidance Points 16 and 17);

level of experience and capacity for conducting ethical and scien-

tific review (see Guidance Point 4); and

local infrastructure, personnel, and laboratory and technical

capacity for conducting the proposed research.

Strategies to overcome these disparities and empower communities

characterisation of the local epidemic through prevalence/

incidence studies and behavioural assessments

scientific exchange, and knowledge and skills transfer, between

sponsors, researchers, communities and their counterparts, and

the countries in which the research takes place, including in the

field of social science;

capacity-building programmes in the science and ethics of

biomedical HIV prevention research by relevant scientific insti-

tutions and local and international organisations;

support to develop national and local ethical review capacity

(see Guidance Point 4);

support to communities from which participants are drawn

regarding information, education, and consensus-building in

biomedical HIV prevention trials;

early involvement of communities in the design and implementa-

tion of HIV prevention product development plans and protocols

(see Guidance Point 2); and

development of laboratory capacity that can support health care

provision as well as research.

In the coming years, there will be increasing demands on clinical sites so that national governments, sponsors, and researchers should think

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

about how to sustain site capacity and retain research staff expertise. Site development may build capacity for a specific trial or enhance the ability of a site to compete more broadly for a range of trials. Given the long time frames of biomedical HIV prevention research, special attention to communication and transparency is needed in order to build and maintain trust with participating communities, and to sustain site capacity even after the end of a trial.

Guidance Point 4:

Scientific and Ethical Review

Researchers and trial sponsors should carry out biomedical HIV prevention trials only in countries and communities that have appropriate capacity to conduct independent and competent scientific and ethical review.

Proposed biomedical HIV prevention trial protocols should be reviewed by scientific and ethical review committees that are located in, and include membership from, the country in which researchers wish to operate. Trials should register with an international trial registry prior to committee review as a condition of approval. Community repre-sentatives should also be involved in review of the trial protocol to insure that the research is informed by the concerns and priorities of the community in which the study is to take place. This process ensures that the proposed research is analysed in scientific and ethical terms by individuals who are familiar with the conditions prevailing in the potential research population. Reviewers should not allow research to begin unless the potential benefits of the experimental intervention outweigh the risks to participating individuals and groups. Independent ethical review of research protocols ensures public accountability and also minimizes concerns with regard to researchers' conflicts of interest because of relationships with the sponsors or pressures from those promoting the research. The scientific and ethical review should involve individuals with training in science, statistics, ethics, and law.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Some countries do not currently have the capacity to conduct inde-pendent, competent, and meaningful scientific and ethical review. If the country's capacity for scientific and ethical review is judged to be inadequate, the sponsor should be responsible for ensuring that adequate structures for scientific and ethical review prior to the start of the research are developed in the country in which the trial will take place — or the research should not take place. Care should be taken to minimise the potential for conflicts of interest, while providing assistance in capacity-building for scientific and ethical review. Capacity-building in scientific and ethical review may also be developed in collaboration with international agencies, organisations within the host country, and other relevant parties.

Scientific and ethical review prior to approval of a trial protocol should take into consideration these issues:

the value and validity of the research protocol community participation and involvement risk-benefit ratio recruitment strategies and methods inclusion and exclusion criteria and screening of participants informed consent procedures and written information sheets provision of support, care, and treatment to participants, and in

respect for potential recruits and enrolled trial participants and

protection of participants' rights

confidentiality, privacy, and data protection measures prevention of stigma and discrimination sensitivity to gender procedures for monitoring enrolled participants quality assurance and safety control plans for post-trial distribution and benefit sharing.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Guidance Point 5:

Clinical Trial Phases

As phases I, II, and III in the clinical development of a biomedical HIV preventive intervention al have their own particular scientific requirements and specific ethical chal enges, researchers and trial sponsors should justify in advance the choice of study populations for each trial phase, in scientific and ethical terms in al cases, regardless of where the study population is found. General y, early clinical phases of biomedical HIV prevention research should be conducted in communities that are less vulnerable to harm or exploitation, usual y within the sponsor country. However, countries may choose, for valid scientific and public health reasons, to conduct any trial phase within their populations, if they are able to ensure sufficient scientific infrastructure and sufficient ethical safeguards.

The initial pre-clinical phase in the development of a biomedical HIV prevention product entails research in laboratories and among animals. The transition to a phase I clinical trial in which testing involves the administration of the product to human subjects to assess safety, and in the case of vaccines to assess immunogenicity, is a time when risks may not yet be well-defined. Hence, specific infrastructures are often required in order to ensure the safety and care of the research participants at these stages. For these reasons, the first administration of a candidate biomedical HIV prevention product in humans should generally be conducted in populations which are not at risk of HIV acquisition, usually in the country of the trial sponsor.

Clinical trial researchers have been designing trials that fall somewhere between phase II (expanded safety and immunogenicity) and phase III (large scale trials to assess efficacy) – called phase IIB trials, or proof of concept trials. Phase IIB trials may provide an indication of

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

an experimental candidate's efficacy but are less costly in terms of money, time, and number of trial participants. However, such phase IIB trials are not designed to provide enough information for regula-tory approval at the end of the trial for an HIV prevention product subject to regulation; instead, these trials test the general concept of the candidate product and efficiently filter out products that lack efficacy. Eventually, a phase III trial would have to be conducted to develop a useable and licensable HIV product.

There may be situations where low- and middle-income countries choose to conduct phases I/II and/or IIB and III among their populations that are relatively vulnerable to risk and exploitation. For instance, this could occur where an experimental HIV vaccine is directed primarily toward a viral strain that does not exist in the trial sponsor's country but does exist in the country in which it is proposed the trial be conducted. Conducting phase I/II trials in the country where the strain exists may be the only way to determine whether safety and immunogenicity are acceptable in that particular population, prior to conducting a phase III trial. Another example might be a country that decides that, due to the high level of HIV risk to its population and the gravity of HIV prevalence in the country, it is willing to test a biomedical HIV prevention product concept that has not or is not being tested in another country. Such a decision may result in obvious benefits to the country in question if an effective product is eventually found. If phase I or phase II trials are conducted in the country intending to participate in an eventual phase III trial, if phases I and II are satisfactory, this may assist in building capacity for phase III trial conduct, including increasing levels of research literacy in the population.

Establishing a biomedical HIV prevention product development programme that entails the conduct of some, most, or all of its clinical trial components in a country or community that is rela-tively vulnerable to harm or exploitation is ethically justified if:

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

the product is a vaccine anticipated to be effective against a

strain of HIV that is an important public health problem in the country;

the country and the community either have, or with assistance

can develop or be provided with, adequate scientific and ethical capability and administrative and health infrastructure for the successful conduct of the proposed research;

community members, policy makers, ethicists, and investiga-

tors in the country have determined that their residents will be adequately protected from harm and exploitation, and that the biomedical HIV prevention product development programme is necessary for and responsive to the health needs and priorities in their country; and

all other conditions for ethical justification as set forth in this

document are satisfied.

In cases in which it is decided to carry out phase I or phase II trials first in a country other than the trial sponsor's country, due consideration should be given to conducting them simultaneously in the country of the trial sponsor, where this is practical and ethical. Also, as a general rule, phase I/II trials that have been performed in the country of the trial sponsor should ordinarily be repeated in the community in which the phase III trials are to be conducted, although this may not be needed, particularly in situations in which a product has demonstrated unexpectedly high efficacy.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Guidance Point 6:

Research Protocols and Study Populations

In order to conduct biomedical HIV prevention trials in an ethical y acceptable manner, researchers and relevant oversight entities should ensure that the research protocol is scientifical y appropriate and that the interventions used in the experimental and control arms are ethical y justifiable.

In order to be ethical, clinical trials of novel biomedical HIV preven-tion tools should be based on scientifically valid research protocols, and the scientific questions posed should be rigorously formulated in a research protocol that is capable of providing reliable responses. Valid scientific questions relevant to biomedical HIV prevention product development are those that seek:

to gain scientific information on the safety and efficacy (degree

of protection) of candidate biomedical HIV prevention products,

and, in the case of vaccine candidates, immunogenicity (ability to

induce immune responses against HIV);

to determine correlates or surrogates of safety and protection in

order to better characterise and elicit protective mechanisms;

to compare different candidate products; and

to test whether biomedical HIV prevention products effective in

one population are effective in other populations.

Furthermore, the selection of the research population should be based on the fact that its characteristics are relevant to the scientific issues raised; and the results of the research will potentially benefit the selected population. In this sense, the research protocol should:

justify the selection and size of the research population from a

scientific point of view;

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

demonstrate how the candidate biomedical HIV prevention

intervention being tested is expected to be beneficial to the

population in which testing occurs;

establish safeguards for the protection of research participants

from potential harm arising from the research (see Guidance

Point 11); and

be sensitive to issues of privacy and confidentiality in recruitment

procedures (see Guidance Point 17).

Guidance Point 7:

Recruitment of Participants

In order to conduct biomedical HIV prevention trials in an ethical y acceptable manner, participation of individuals should be voluntary and the selection of participating communities and individuals must be fair and justified in terms of the scientific goals of the research.

Selection and recruitment of communities and individuals for partici-pation in a trial must be fair and should create a research climate which shows respect for all persons. This encompasses decisions about who will be included through the formulation of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and through the strategy adopted for recruiting participants. The scientific goals of the study should be the primary basis for determining the individuals who will be recruited and enrolled. Individuals should not be excluded from the opportunity to participate without a good scientific reason or a susceptibility to risk that justifies their exclusion. Social and cultural factors should be considered to determine the vulnerability within the community of individuals who are either included or excluded. In particular, gender-sensitive approaches are key when designing recruitment procedures and special attention needs to be paid to the inclusion or exclusion of pregnant women.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

In some situations, voluntariness of participation may be

compromised by factors such as social marginalization, political

powerlessness, and economic dependence. Voluntariness of

participation may also be compromised where there is a cultural

tradition of men holding decision making authority in marital

relationships, parental control of women, and other forms of

social subjugation and coercion (see Guidance Point 9). In some

communities, it is customary to require the authorization of a third

party, such as a community elder or head of a family, in order for

investigators to enter the community or to approach individuals.

However, the third party only gives permission to invite individuals

to participate and such authorisation or influence must not be used

as a substitute for individual informed consent. Trials should not be

conducted where truly voluntary participation and ongoing free

informed consent cannot be obtained. Authorisation by a third

party in place of individual informed consent is permissible only

in the case of some minors who have not attained the legal age of

consent to participate in a trial. In cases where it is proposed that

minors will be enrolled as research participants, specific and full

justification for their enrolment must be given, and their own assent

or consent must be obtained in light of their evolving capacities

(see Guidance Point 10).

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Guidance Point 8:

Vulnerable Populations

The research protocol should describe the social contexts of a proposed research population (country or community) that create conditions for possible exploitation or increased vulnerability among potential trial participants, as wel as the steps that wil be taken to overcome these and protect the rights, the dignity, the safety, and the welfare of the participants.

By definition, HIV prevention research must follow the epidemic. In order to test if a biomedical HIV prevention intervention works, large numbers of individuals at high risk for HIV infection must be recruited for clinical trials. Sites based in communities with mature HIV epidemics have lower incidence rates and may be most appropriate for safety studies. Sites in communities with younger epidemics may be better suited for efficacy trials. However, partici-pating communities and populations, particularly for large-scale efficacy trials, will generally be characterized by multiple vulnera-bilities. The same factors that put these individuals at higher risk for exposure to HIV also make them vulnerable to cultural exclusion, social inequality, economic exploitation, and political oppression. Examples of populations that may have an increased vulnerability include women, children and adolescents, men who have sex with men, injecting drug users, sex workers, transgender persons, indig-enous populations, the poor, the homeless, and communities from resource-poor settings in high-income and low- and middle-income countries. At the same time, it is precisely these populations who stand to benefit most from the successful development of a new biomedical HIV prevention product or method. For these reasons, it is imperative to ensure protection of the rights of participants in biomedical HIV prevention trials, and respect for their dignity, safety, and welfare.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Decision-making around conducting a biomedical HIV prevention

trial needs to consider in what ways the trial might increase or decrease

vulnerabilities. On the one hand, a trial might increase a participant's

risk of exposure to stigmatisation and discrimination if it highlights a

population's increased vulnerability to HIV exposure. On the other

hand, a trial might decrease vulnerability, if it empowers the community

or provides tangible assistance to participants, for example by improving

the accessibility, affordability, and quality of appropriate healthcare

services in the community. A social and political analysis should be

carried out early on in planning the research process, to assess determi-

nants of vulnerability, such as poverty, gender, age, ethnicity, sexuality,

health, employment, education, and legal conditions in potential partic-

ipating communities. Findings from this analysis should inform the

design of research protocols, which should be sensitive to emerging

information on incidental risks of social harm throughout the course

of a trial. Research protocols might also include ongoing independent

monitoring of a trial in relation to its impact on the vulnerabilities of

communities participating in the study (see Guidance Point 17).

The particular aspects of a social context that create conditions for exploi-tation or increased vulnerability should be described in the research protocol, as should the safeguards and measures that will be taken to prevent and overcome them. In some potential research populations (countries or communities), conditions affecting potential vulnerability or exploitation may be so severe that the risk outweighs the benefit of conducting the study in that population. In such populations, biomed-ical HIV prevention trials should not be conducted.

Sensitivity to factors of potential vulnerability, including language and cultural barriers, should inform procedures for recruiting and screening potential participants, informed consent processes, and the support, care, and treatment that participants receive in relation to the trial. If a scien-tifically appropriate population is identified as vulnerable to social harm, specific safeguards should be implemented to protect individual partici-pants, such as ensuring confidentiality, the freedom to decline joining the study and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Guidance Point 9:

Women

Researchers and trial sponsors should include women in clinical trials in order to verify safety and efficacy from their standpoint, including immunogenicity in the case of vaccine trials, since women throughout the life span, including those who are sexual y active and may become pregnant, be pregnant or be breastfeeding, should be recipients of future safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention interventions. During such research, women's autonomy should be respected and they should receive adequate information to make informed choices about risks to themselves, as wel as to their foetus or breastfed infant, where applicable.

Women throughout the life span, including those who are sexually active and may become pregnant, be pregnant or be breastfeeding, should be recipients of future safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention products and therefore should be eligible for enrolment in biomedical HIV prevention trials, both as a matter of equity and because in many communities throughout the world women, particularly young women, are at higher risk of HIV exposure. Therefore, the efficacy of candidate biomedical HIV prevention products, and their immunogenicity in the case of vaccines, should be established for women. Clinical trials should also be designed with the intent of establishing the safety of candidate biomedical prevention products for the health of the woman and, where appli-cable, her foetus, breastfed infant and, in the case of vaginal or rectal microbicides, her sexual partners.

If the safety of the biomedical HIV prevention product for a pregnant women and her foetus has not been established prior to commence-ment of the trial, women who become pregnant in the course of the trial might be discontinued from using the product, which would

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

result in loss to follow-up of the participating women. Therefore the question of whether a safety study for pregnant women should be conducted early on in the research, at the stage when a candidate has sufficient promise to advance into a Phase IIB or Phase III efficacy trial in adults or only after the trial product has been shown to be effective should be discussed and resolved on a case-by-case basis early on in the planning of the research design. In any event, researchers should monitor adverse events among pregnant women and women who become pregnant in the course of the trial, notably in the case of a miscarriage, to determine their relatedness to the biomedical HIV preventive intervention.

The most notable data gap in the evaluation of some prevention

methods, particularly in phase I and II trials, is adequate evaluation

of safety and efficacy among women. Barriers for women partici-

pating in trials include contraceptive requirements, issues related

to current or future fertility, concerns about safety for the foetus,

and fear of being labelled as being at higher risk for HIV exposure.

Also, women present issues of particular complexity with regard to

recruitment and informed consent. In some cultures, women and

girl adolescents may not be able to exercise true autonomy in light

of the influence of their parents or sexual partners (see Guidance

Point 7). In others, young people may be more informed than their

parents, and their view and their parents' or partners' views on

their participation may differ. Further, the need for HIV testing or

pregnancy testing to assess eligibility for inclusion in a trial may

raise difficult issues regarding the maintenance of appropriate confi-

dentiality. Researchers and research staff should improve recruit-

ment strategies by anticipating and finding solutions to address

and overcome these barriers (see Guidance Point 7). Appropriate

reproductive and sexual health counselling and ancillary services,

including family planning, should be provided to trial participants.

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

Although the enrolment of pregnant or breastfeeding women complicates the analysis of risks and benefits, because both the woman and the foetus or infant could be benefited or harmed, such women should be viewed as autonomous decision-makers, capable of making an informed choice for themselves and for their foetus or child. In order for pregnant women to be able to make an informed choice for their foetus/breastfed infant, they should be duly informed about any potential for teratogenesis and other known or unknown risks to the foetus and/or the breastfed infant. If there are risks related to breastfeeding, women should be informed of the availability of nutritional substitutes and other supportive services. Researchers should observe and study the positive and adverse effects on the children of these women. They should maintain pregnancy registries to collect data on outcomes of pregnancies that inadvertently occur during the trial, follow-up babies born to women participants, and take due measures for protection of privacy and personal data. In the particular case of trials of prevention of mother-to-child transmis-sion, both women and their infants who became infected should also be assessed for the development of antiretroviral resistance and its potential for effects on subsequent therapeutic options.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

Guidance Point 10:

Children and Adolescents

Children and adolescents should be included in clinical trials in order to verify safety and efficacy from their standpoint, in addition to immunogenicity in the case of vaccines, since they should be recipients of future biomedical HIV preventive interventions. Researchers, trial sponsors, and countries should make efforts to design and implement biomedical HIV prevention product development programmes that address the particular safety, ethical, and legal considerations relevant for children and adolescents, and safeguard their rights and welfare during participation.

Children3, including infants and adolescents, should be eligible for enrolment in biomedical HIV preventive intervention trials, both as a matter of equity and because in many communities throughout the world children are at a higher risk of HIV exposure. Infants born to HIV-infected mothers are at risk of becoming infected during birth and during the postpartum period through breastfeeding. Many adolescents are also at higher risk of HIV infection due to sexual activity, lack of access to HIV prevention education and means, and through injecting drugs with non-sterile equipment.

Therefore, biomedical HIV prevention product development programmes should consider the needs of children for a safe and effective preventive intervention; should research the legal, ethical, and health considerations relevant to their participation in biomedical trials; and should enrol children in clinical trials designed to establish safety and efficacy for their age groups, including establishing immunogenicity in the case of vaccines, if their health needs and the ethical considerations relevant to their

3 As defined by the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 1: "… a child means

every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier."

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

situation can be met. Those designing biomedical HIV prevention product development programmes that might include children should do so in consultation with groups dedicated to the protec-tion and promotion of the rights and welfare of children, both at international and national levels.

It is generally understood that adolescents, prior to initiation of

sexual activity and exposure to any risk of HIV infection, will be

the primary target for any public health intervention involving

a successful biomedical intervention. In the case of HIV vaccine

candidates and other products requiring licensure that would have

an indication for use in both adolescents and adults, it is impera-

tive that there be no delays in achieving simultaneous licensure/

registration for both populations. It is therefore recommended in

such cases, that adolescents be included in trials as soon as possible

when a candidate has sufficient promise to advance into a Phase

IIB or Phase III efficacy trial in adults (see Guidance Point 5).

The use of bridging studies designed for safety (and, in the case of

an HIV vaccine, immunogenicity testing), but not including HIV

infection as a primary endpoint could be considered as an alterna-

tive for younger adolescents, to be carried out in parallel to Phase

III trials in adults.

There may be legal barriers to enrolment of younger adolescents into a clinical trial in which sexual activity is directly linked to achieving primary endpoints. It is imperative that trials are conducted in compliance with the protective laws and regulations applicable at the trial sites, including those related to legal age of consent, the age of majority, the legal age for consensual sex, legal obligations to report abuse or neglect, and other aspects which may have an impact on the conduct of biomedical HIV preventive intervention trials. Thus, undertaking a survey of applicable local laws is an essential requirement to ensure required compliance prior to making plans for such trials in a particular country.

UNAIDS / WHO guidance document

As with all other trials involving children, the permission of a parent or legal guardian is required along with the assent of the child. Unless exceptions are authorised by national legislation, consent to participate in a biomedical HIV preventive intervention trial must be secured from the parent or guardian of a child who is a minor, before the enrolment of the child as a participant in a vaccine trial. The consent of one parent is generally sufficient, unless national law requires the consent of both. Every effort should be made to obtain assent to participate in the trial also from the child according to the evolving capacities of the child, and his or her refusal to participate should be respected.

In some jurisdictions, individuals who are below the age of consent are authorised to receive, with their active consent and without the consent or awareness of their parents or guardians, such medical services as therapeutic abortion, contraception, treatment for illicit drug use or alcohol abuse, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections. In some of these jurisdictions, such minors are also authorised to consent to serve as participants in research in the same categories without the agreement or the awareness of their parents or guardians, provided the research presents no more than "minimal risk". However, such authorisation does not justify the enrolment of minors as participants in biomedical HIV prevention trials without the consent of their parents or guardians.