The effectiveness and safety of treatments used for polycystic ovarian syndrome management in adolescents: a systematic review and network meta-analysis protocol

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125 DOI 10.1186/s13643-015-0105-4

The effectiveness and safety of treatmentsused for polycystic ovarian syndromemanagement in adolescents: a systematicreview and network meta-analysis protocol

Reem A. Al Khalifah1,2,3, Iván D. Flórez1,4* Brittany Dennis1, Binod Neupane1, Lehana Thabane1,5,6and Ereny Bassilious2

Background: Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common reproductive endocrine disease that is seen amongadolescent women. Currently, there is limited evidence to support treatment options leading to considerable variationin practice among healthcare specialists. The objective of this study is to review and synthesize all the available evidenceon treatment options for PCOS among adolescent women.

Methods/design: We will conduct a systematic review of all randomized controlled trials evaluating the use ofmetformin, oral contraceptive pills as monotherapy, or as combination with pioglitazone, spironolactone, flutamide,and lifestyle interventions in the treatment of PCOS in adolescent women ages 11 to 19 years. The primary outcomemeasures are menstrual regulation and change hirsutism scores. The secondary outcome measures include acnescores, prevalence of dysglycaemia, BMI, lipid profile, total testosterone level, and adverse events. We will performliterature searches through Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL),and gray literature resources. Two reviewers will independently screen titles and abstracts of identified citations, reviewthe full texts of potentially eligible trials, extract information from eligible trials, and assess the risk of bias and quality ofthe evidence independently. Results of this review will be summarized narratively and quantitatively as appropriate. Wewill perform a multiple treatment comparison using network meta-analysis to estimate the pooled direct and indirecteffects for all PCOS interventions on outcomes if adequate data is available.

Discussion: PCOS treatment poses a clinical challenge to the patients and physicians. This is the first systematic reviewand network meta-analysis for PCOS treatment in adolescents. We expect that our results will help improve patient care,unify the treatment approaches among specialists, and encourage research for other therapeutic options.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO

Keywords: Adolescents, Polycystic ovarian syndrome, Hirsutism, Menstrual irregularity, Acne, Body mass index,Dysglycaemia

* Correspondence: 1Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics, McMaster University,Juravinski Site, G Wing, 2nd Floor, 711 Concession Street, Hamilton, ON L8V1C3, Canada4Department of Pediatrics, University of Antioquia, Medellín, ColombiaFull list of author information is available at the end of the article

2015 Al Khalifah et al. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0International License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, andreproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link tothe Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiverapplies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

pills (OCP) to control symptoms of hyperandrogenism

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common repro-

or metformin therapy in patients with impaired glucose

ductive endocrine disease encountered among adolescents

tolerance or features of metabolic syndrome [. How-

and young women [. Its prevalence varies between 1.8

ever, there is significant variability in clinical practice,

and 15 % depending on the diagnostic criteria used and

depending on whether the physician and patient's primary

ethnicity . Patients with PCOS can present with a

goal of treatment is to treat the symptoms of hyperandro-

constellation of symptoms including chronic anovulation

genism or the features of metabolic syndrome

(amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, irregular menstrual cycles),

Additionally, in clinical practice anti-androgenic medica-

clinical features of hyperandrogenism (acne and hirsut-

tions such as spironolactone, flutamide, and insulin sensi-

ism), biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, polycys-

tizing agents such as pioglitazone are used as add-on

tic ovaries on ultrasound, and features of metabolic

therapy when OCP or metformin fail to produce the

syndrome. Oligomenorrhea is the presenting feature in

clinically desired outcomes yet the Endocrine

about 75 % of cases [, while hirsutism and acne are

Society guidelines do not comment on their use in

present in 60–70 % of cases and contribute to psycho-

the adolescent population.

logical distress in adolescent patients .

To date, there is one systematic review and meta-

Three different diagnostic criteria have been used for

analyses in adolescents (in press) that identified low num-

the diagnosis of PCOS: the National Institutes of Health

ber of low quality evidence from head-to head trials and

(NIH), the Rotterdam, and the Androgen Excess Society

identified large number of trials that compared metformin

Criteria All of them require the presence of men-

to placebo, OCP to placebo, and other PCOS combination

strual cycle disturbance and presence of clinical and/or

therapy ]. A traditional meta-analysis can only evaluate

biochemical hyperandrogenism, while the last two re-

the direct treatment efficacy of two treatment approaches

quire the presence of polycystic ovarian morphology on

at a time while a network meta-analysis can provide effect

ultrasound To date, the preferred diagnostic cri-

estimates for all direct and indirect treatment comparisons

teria in adolescents are the NIH criteria [

[]. Therefore, we aim to conduct a network meta-

The etiology of PCOS is complex and not well under-

analysis to address the following objectives: (1) assess the

stood. Primary intrinsic ovarian pathology in combination

effectiveness and safety of using metformin and OCP as

with hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis abnormalities

monotherapy in adolescents with PCOS; (2) assess the ef-

may lead to increased ovarian androgen secretion [,

fectiveness and safety of using metformin and/or OCP in

Insulin resistance with compensatory hyperinsulinemia

combination with pioglitazone, spironolactone, flutamide,

may also play a role as it can lead to direct stimulation of

and lifestyle interventions, as evaluated across multiple

ovarian and adrenal androgen secretion, which leads to

outcomes such as menstrual cycle regulation, improve-

decreased hepatic sex hormone binding globulin synthesis

ment in clinical and or biochemical evidence of hyperan-

and therefore, to an increased bioavailability of free testos-

drogenism, and metabolic profile in adolescents with

terone level ]. Insulin resistance is involved in the

PCOS; (3) evaluate the effectiveness of different formula-

development of cardiometabolic disturbances such as dys-

tions of OCPs on hirsutism and acne scores.

glycaemia, hyperlipidemia, and obesity and it hasbeen described that between 18 and 24 % of adolescents

with PCOS have some degree of abnormal glucose me-

This systematic review and network meta-analysis proto-

tabolism [–These patients are at increased risk

col is registered on PROSPERO International prospective

of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction,

register of systematic reviews (CRD42015016148). The re-

angina, and psychiatric diseases in addition to

port will comply with the Preferred Reporting Items for

gynecological and obstetrical complications, such as in-

Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis Protocols

fertility, higher rate for pregnancy loss, gestational dia-

(PRISMA-P) [].

betes, premature delivery, as well as gynecological andnon-gynecological cancers . In addition to the

Eligibility criteria

aforementioned co-morbidities, patients with PCOS ex-

The search for studies will be limited to randomized

perience a low perceived health quality over lack of

clinical trials (RCT) (including all designs such as cross-

symptom improvement, primarily with weight control,

over, cluster, and patient-randomized clinical trials) asses-

hirsutism, acne, menstrual irregularity, and infertility as

sing the efficacy, effectiveness, or safety of different

inferred from qualitative studies

regimen for the treatment of PCOS that enrolled adoles-

Optimal first line treatment of PCOS in adolescents

cent girls ages 11–19 years. The definition of adolescent

remains controversial. Current Endocrine Society treatment

age group is based on the widely accepted World Health

guidelines first recommend lifestyle changes (dietary and

Organization definition for adolescent Studies that

exercise modification) followed by either oral contraceptive

include both adolescents and adults participants will be

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

included in the review, and upon contact, we will ask au-

search of bibliographies of identified randomized controlled

thors to provide separate data for the adolescent partici-

trials and guidelines; (2) trials registries (Clinicaltrials.gov,

pants. If we are unable to obtain this information, we will

World Health Organization WHO International Clinical

include the study and we will conduct subgroup analyses

Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, controlled-trials.com

in order to assess the difference between studies which in-

and the National Institutes of Health database of funded

cluded only adolescents and studies which included both

studies for ongoing or unpublished trials); and (3) confer-

adolescents and adults. Sub-studies or secondary ana-

ences preceding and abstracts of the North American and

lysis of reported eligible studies will be excluded to

European Endocrine Society and The Society of Adolescent

avoid duplication.

Medicine and Health. Search alerts are set up for monthly

The diagnosis of PCOS will be based on the known

notification, and the search will be repeated before the final

PCOS diagnostic criteria: Endocrine Society Guidelines,

manuscript submission to identify any new literature. We

NIH criteria, Rotterdam criteria, and the Androgen Excess

will contact the authors of unpublished work to establish

Society criteria We will exclude studies that in-

eligibility and methodological quality of the study.

cluded normal control participants or patients with othercauses of oligomenorrhea or hyperandrogenism, such as

hyperprolactinemia, thyroid dysfunction, androgen secret-

Two reviewers (RA and IF) will independently and in

ing tumors, or late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

duplicate screen the title and abstract available of identi-

We will include studies that evaluated single and/or

fiable articles to assess its eligibility. In case of disagree-

combined interventions, at any dose, such as metformin,

ment, the full text will be retrieved and reviewed

OCP, pioglitazone, spironolactone, flutamide, and life-

independently by one of the authors (EB), to resolve dis-

style interventions. In order to be included, the study

crepancy. We will refer to inclusion and exclusion cri-

will have had to report the effectiveness of one of these

teria during the screening process. Records of ineligible

interventions and the intervention effect on one or more

articles along with the reason for ineligibility will be

of the outcomes of interest.

saved for future reference. Eligible articles citations will

Our primary outcomes are menstrual cycle regulation

be saved in EndnoteX6 library. We will include the

and hirsutism scores. The secondary outcomes include

PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating the search and

acne scores, prevalence of dysglycaemia, BMI, total tes-

screening process (Fig. We will contact authors of

tosterone level, lipid profile (triglyceride, total choles-

primary studies during data extraction to provide any

terol, LDL, HDL), and adverse events; Table shows the

definitions of outcome measures. We chose not to re-port on pregnancy outcomes because it necessities chan-

ging the scope of the review to involve fertility induction

The study data will be collected in standardized online

medications. Hence, we will exclude studies that only

data extraction forms (Google forms) according to pre-

used fertility induction medications and which primary

specified instructions. The data extraction form will

outcome of interest was pregnancy.

include information pertaining to study background, lan-guage of publication, country, funding sources, confirm

Data sources and search strategy

study eligibility, participant ages, PCOS diagnostic cri-

We performed literature search through Ovid MEDLINE,

teria, the study design, number of intervention groups,

Ovid EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Con-

intervention details, number of participants allocated to

trolled Trials (CENTRAL) from the database inception to

each intervention group, randomization, concealment of

January 2015 using combination of controlled terms, i.e.,

allocation, blinding, length of follow up, analysis type,

Medical Subject Heading (MeSH), Emtree terms, and

outcome definition, unit of measurement, ascertainment

free-text terms with various synonyms for polycystic

of the outcome, estimate of intervention effect with con-

ovarian syndrome (PCOS), adolescent, metformin, pio-

fidence interval, and missing follow up data. When stud-

glitazone, oral contraceptive pills, flutamide, and life-

ies measure outcomes at more than one time point, we

style interventions ).

will collect results for the last measurement point in the

We used the randomized controlled trial filter created

study. The data extraction form will be pilot tested by all

from McMaster University for Ovid Embase platform

reviewers independently before its use. Four reviewers

and the Cochrane library filter for Ovid Medline platform

will perform data extraction (RA, IF, EB, BD), working

These filters provide a good balance between sensi-

in pairs independently and in duplicate. In case of dis-

tivity and specificity. Our search strategy was developed in

agreement in assessing the methodological quality of the

liaison with an experienced librarian. No language, publica-

study, we will try to resolve it by consensus. If consensus

tion status, or date limit was used. Additionally, we per-

cannot be reached, a third designated reviewer from the

formed a gray literature search through (1) manual hand

team will be involved.

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

Table 1 Outcome measures

Measurement of variable (units)

Statistical estimates andmeasurement of associationof this outcome

Menstrual regulation

Number of girls achieved regular menses

Number of cycles per year

Mean difference ± SD

Ferriman Gallawey score

Mean difference ± SD

Lesion counting or grading

Standardized mean difference ± SD

The rate of occurrence of T2DM, impaired glucose tolerance,

and impaired fasting glucose assessed by oral glucose tolerancetest and/or fasting blood glucose, and/or HBA1c

Mean difference ± SD

Total testosterone level

Mean difference ± SD

Total cholesterol

Mean difference ± SD

Mean difference ± SD

Mean difference ± SD

Mean difference ± SD

Number of girls developed:

1- GI: all GI related adverse events:

• Nausea• Vomiting• Diarrhea• Constipation• Abdominal pain• Flatulence• Gastritis• GI bleeding

2- thrombosis: all vascular events related to thrombusformation such as:

• Deep venous thrombosis• Stroke• Myocardial infarction• Pulmonary embolism

3- serious: adverse events that are of majormorbidity such as:

• Any bleeding not including GI bleed• Lactic acidosis• Liver failure• Renal failure• Vasculitis• Electrolyte imbalance• Agranulocytosis• Photosensitivity• Hypertension• Pancreatitis• Anaphylaxis• Chorea• Depression

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

Table 1 Outcome measures (Continued)

4- minor: adverse events that are of minormorbidity such as:

• Headache• Fatigue• Beast tenderness• Vaginal bleeding (spotting)• Edema• Weight gain• Metallic taste• Muscle cramp• Rash• Fever• Hot flashes• Glucose intolerance• Infection

OR odds ratio, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI body mass index, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HDL high-density lipoprotein, GI gastrointestinal

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

risk," or "unclear risk." We will further categorize the "un-

Two independent reviewers will assess each included study

clear risk" to "probably low risk" or "probably high risk" in

for risk of bias using the modified Cochrane handbook for

order to give a better understanding of the unclear risk of

systematic reviews of interventions tool [, which as-

bias score. We will rate the overall risk of bias score for

sesses six elements: (1) sequence generation, (2) allocation

each study as "high risk" if the study meets more than two

concealment, (3) blinding of participants, personnel and

criteria for high risk of bias, "moderate risk of bias" if the

outcome assessors, (4) completeness of follow up, (5) se-

study meets one to two criteria for high risk of bias, and

lective outcome reporting, and 6) presence of other biases.

"low risk of bias" if the study does not meet any high risk

Each domain will be assigned a score of "low risk," "high

of bias criteria [].

Standard direct comparisonsWe will perform a pairwise meta-analysis using R soft-ware. Effect estimates and their 95th confidence interval(CI) will be calculated using risk ratio (RR) for binaryoutcomes and mean difference for continuous outcomesif they are reported using the same metrics; otherwise,estimates reported using different metrics will be con-verted into standardized mean difference (SMD). Wewill pool all direct evidence using random-effect meta-analysis with the maximal likelihood (ML) estimatorWe will assess for heterogeneity by estimating thevariance between studies using the chi-square test andquantify it using the I2 test statistic. We will interpretthe I2 using the thresholds set forth by the CochraneCollaboration

The network meta-analysisGiven that many of the treatment combinations availableto treat PCOS were not compared in head-to-head stud-ies, a network meta-analysis (NMA) will be necessary toprovide effect estimates for all indirect comparisonsWe will perform a multiple treatment comparison

Fig. 1 The primary selection process

to estimate the pooled direct, indirect, and the network

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

estimates (mixed evidence from direct and indirect esti-

hierarchical regression model but considers multiple com-

mates) for all PCOS interventions on outcomes if the as-

ponents of an intervention as dummy variables in the same

sumptions of homogeneity and similarity are judged to

model. Hence, the analysis allows the estimation of the ef-

be reasonable. Effect estimates will be presented along

fects and ranking of a combination of all possible and ap-

with their corresponding 95 % credibility intervals (CrIs);

propriate components. Thus, it is possible to explore such

these are the Bayesian analog of 95 % CIs. However,

a combination that could have been the best for the treat-

mixed evidence will only be used if the consistency as-

ment of PCOS but has never been tested before in any

sumption is met.

trial. Further, such an analysis allows the assessment of

We will fit a Bayesian random-effect hierarchical

additive or multiplicative (interaction) effects between two

model with non-informative priors using vague normal

or more components if sufficient data are available. We

distribution (mean 0, variance 10,000) and adjusting for

will re-analyze the data under complex intervention ap-

correlation between effects in multi-arm trials. We will

proach as well [to assess if there exists a potentially bet-

ter combination of components which have been ever or

Monte-Carlo (MCMC) simulation technique running

never assessed.

the analysis in four parallel chains. We will use a series

We will perform the Bayesian network meta-analysis

of 100,000 burn-in simulations to allow convergence

in JAGS (version 3.4.0) or WinBUGS software (version

and then a further 20,000 simulations (succeeding

1.4.3, MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) inter-

50,000 simulations saved at an interval of 10 in each

facing through R software.

chain) to produce the outputs. We will assess modelconvergence using Gelman and Rubin diagnostic test ].

The Bayesian model provides flexibility for moderate

In case there is significant heterogeneity and inconsistency,

levels of treatment heterogeneity, sampling variability,

we will use meta-regression to explain the heterogeneity,

and incoherence This model introduces a ran-

provided we have enough data to do so; otherwise, we will

dom effect representing any changes in the observed

perform subgroup analyses. We will perform meta-

treatment effect that may be due to the comparison

regression using study level covariates: methodological

being made We will interpret variability in this

quality (high risk of bias versus low risk of bias), partici-

random effect as incoherence [We will use the

pant's average age, BMI status (obese and/or overweight

node-splitting method to detect incoherence between

BMI ≥25 kg/m2 versus normal <25 kg/m2), homeostatic

direct and indirect evidence within a closed loop as

model assessment (HOMA-IR) (high and moderate ≥3

well as identify loops with large inconsistency [

versus low <3), medication dose, length of treatment

We will measure the goodness-of-fit of the model using

(≥3 months versus <3 months), use of ultrasound to docu-

the deviance information criterion (DIC)

ment polycystic ovaries (used versus not used), and studies

To ensure interpretability of the NMA results, we will

that included young adults versus adolescents only to

present the network geometry, the results with probabil-

examine the improvement or change in model fit after co-

istic statements, and also the estimates of interventions

variates are included into the model. We will also perform

effects and corresponding 95 % CrIs, as well as forest

a subgroup analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of differ-

plots. We will first rank the intervention and report each

ent oral formulations of contraceptive pill on changes of

interventions' probability of ranking first (being the best

hirsutism and acne scores.

treatment) as well as the surface under the cumulativeranking curve (SUCRA) values High SUCRA values

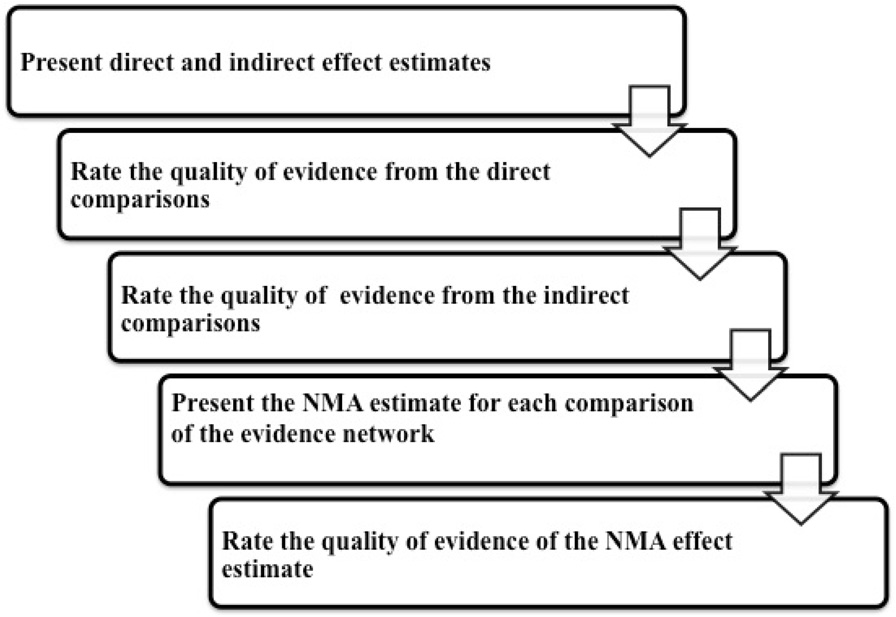

Rating the confidence in estimates of the effect in NMA

are expected for the best treatments, and low SUCRA

The confidence in the estimates (quality of evidence) for

values are expected for the worst treatments.

each reported outcome will be assessed independently

The above analysis assumes that the interventions are

by two reviewers (RA, IF) using the Grading of Recom-

competing (suitable when most components forming an

mendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

intervention are pharmaceutical and hence cannot go to-

Working Group (GRADE Working Group) approach;

gether), so that each combination is considered to be a

see Fig. for the flow of quality assessment The

separate treatment. For example, a combination of com-

quality of evidence is categorized by GRADE into four

ponents of metformin, flutamide, and exercise forming an

levels: high quality, moderate quality, low quality, and

intervention and another combination of metformin and

very low quality. For the direct comparisons, we will as-

exercise forming another intervention are treated as com-

sess and rate each outcome based on the five GRADE

peting interventions and assesses whether one combination

categories: risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indir-

is better than another. However, it is possible to perform

ectness, and publication bias

the network meta-analysis treating these combinations as

For the assessment of confidence in the estimates ob-

complex intervention [Such an analysis fits a similar

tained in the NMA, we will use the recent approach

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

Table 2 Search strategy: Ovid MEDLINE(R) in-process and othernon-indexed citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and OvidMEDLINE(R) 1946 to January 29, 2015

Fig. 2 The quality assessment flow diagram

young adult*.mp.

recommended by the GRADE working group We

will assess and rate the confidence in all the indirect com-

parisons, if available, obtained from first order loops fol-

lowing the five GRADE categories used for assessing the

direct comparisons in addition to the intransitivity assess-

exp Polycystic Ovary Syndrome/

ment. Then, we will rate the confidence in each NMA ef-fect estimate using the higher quality rating when both

direct and indirect evidence are present. However, the es-

timate can be rated down for incoherence

exp Hyperandrogenism/

PCOS treatment in adolescents poses clinical chal-

lenges to patients and physicians. To our best know-

ledge, our study will be the first NMA in adolescents

(polycystic ovar* adj3 (syndrome or disorder or disease)).tw.

to investigate the effectiveness and safety of using

metformin and OCP as monotherapy as well as in

combination with pioglitazone, spironolactone, fluta-mide, or lifestyle interventions.

Our planned approach for this review has many

strengths. We will implement a wide search strategy that

included published and unpublished work. As adolescent

women share some similar physiology with adult women

and in an effort to overcome publication bias, we also

exp Contraceptives, Oral/

plan to include studies that included adolescents andyoung adults. Additionally, we aim to report on many

patient important outcomes as inferred from previous

qualitative research. Similar to previous systematic re-

views in adults with PCOS, we anticipate that we will

identify studies which use different definitions of PCOS,

various definitions for outcome measures of interest,

and small sample sizes These factors may pose po-tential limitations to our study.

We hope that this review will provide hierarchical evi-

dence to improve patient care, help unify the treatment

approaches among specialists, and encourage research

exp spironolactone/

for new therapeutic options.

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

Table 2 Search strategy: Ovid MEDLINE(R) in-process and other

Table 2 Search strategy: Ovid MEDLINE(R) in-process and other

non-indexed citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid

non-indexed citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid

MEDLINE(R) 1946 to January 29, 2015 (Continued)

MEDLINE(R) 1946 to January 29, 2015 (Continued)

exp hyperandrogenism/

exp Health Promotion/

exp oral contraceptive agent/

randomized controlled trial.pt.

Controlled clinical trial.pt.

clinical trials as topic.sh.

14 and 24 and 52 and 60

exp spironolactone/

exp pioglitazone/

Embase 1974 to 2015 January 27

exp health promotion/

exp diet therapy/

young adult*.mp.

Double blind.tw.

Single blind.tw.

exp ovary polycystic disease/

14 and 49 and 54 and 57

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

Table 2 Search strategy: Ovid MEDLINE(R) in-process and other

Author details1Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics, McMaster University,

non-indexed citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid

Juravinski Site, G Wing, 2nd Floor, 711 Concession Street, Hamilton, ON L8V

MEDLINE(R) 1946 to January 29, 2015 (Continued)

1C3, Canada. 2Department of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology andMetabolism, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. 3Department of

Cochrane central: search up to 30/01/2015 20

Pediatrics, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 4Department of

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Adolescent] explode all trees

Pediatrics, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. 5Department ofPediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. 6Department of

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Child] explode all trees

Pediatrics and Anesthesia, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

#3 MeSH descriptor: [Young Adult] explode all trees

Received: 15 July 2015 Accepted: 25 August 2015

#4 young adult.tw

Li R, Zhang Q, Yang D, Li S, Lu S, Wu X, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Polycystic Ovary Syndrome] explode all trees

syndrome in women in China: a large community-based study. Hum

#8 Stein Leventhal Syndrome or Polycystic Ovar* or PCOS. tw

Christensen SB, Black MH, Smith N, Martinez MM, Jacobsen SJ, Porter AH, et

#9 MeSH descriptor: [Hirsutism] explode all trees

al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Fertil Steril.

#10 MeSH descriptor: [Hyperandrogenism] explode all trees

Yildiz BO, Bozdag G, Yapici Z, Esinler I, Yarali H. Prevalence, phenotype and

#11 hyperandrogen*. tw

cardiometabolic risk of polycystic ovary syndrome under differentdiagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(10):3067

#12 Hirsutism. tw

Roe AH, Dokras A. The diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in

#13 #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12

adolescents. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4(2):45–51.

Kumarapeli V, Seneviratne Rde A, Wijeyaratne C. Health-related quality of life

#14 metformin or glucophage or pioglitazone or oral contraceptive pill

and psychological distress in polycystic ovary syndrome: a hidden facet in

or OCP or Ortho Tri-Cyclen or Ortho-CyclenCyclessa or Mircette or

South Asian women. BJOG. 2011;118(3):319–28.

Yasmin or diane or Desogen or Flutamide or spironolactone or

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group.

Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks

#15 MeSH descriptor: [Metformin] explode all trees

related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19–25.

Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS

#16 MeSH descriptor: [Contraceptives, Oral, Hormonal] explode all trees

Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force

#17 MeSH descriptor: [Spironolactone] explode all trees

report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):456–88.

Zawadski J, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome:

#18 MeSH descriptor: [Flutamide] explode all trees

towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens J, Haseltine F, Merriam G,

#19 MeSH descriptor: [Life Style] explode all trees

editors. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. 1st ed. Boston: Blackwell ScientificPublications; 1992. p. 377–84.

#20 #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19

Hardy TS, Norman RJ. Diagnosis of adolescent polycystic ovary syndrome.

Steroids. 2013;78(8):751

#21 #7 and #13 and #20 in Trials

Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, Hoeger KM, Murad MH, Pasquali R, etal. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society

clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):4565–92.

BMI: body mass index; DIC: deviance information criterion; GRADE: Grading of

Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(12):1223–36.

Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NIH: National

Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA, Chazenbalk G, Azziz R. Polycystic ovary syndrome:

Institutes of Health; NMA: network meta-analysis; OCP: oral contraceptive pill;

etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(4):219–31.

PCOS: polycystic ovarian syndrome; RCT: randomized controlled trials;

Pauli JM, Raja-Khan N, Wu X, Legro RS. Current perspectives of insulin

T2DM: type two diabetes mellitus.

resistance and polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabet Med. 2011;28(12):1445–54.

Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanismand implications for pathogenesis. Endocr Rev. 1997;18(6):774–800.

Competing interests

Rehme MF, Pontes AG, Goldberg TB, Corrente JE, Pontes A. Clinical

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

manifestations, biochemical, ultrasonographic and metabolic of polycysticovary syndrome in adolescents. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2013;35(6):249–54.

Li L, Chen X, He Z, Zhao X, Huang L, Yang D. Clinical and metabolic features

Authors' contributions

of polycystic ovary syndrome among Chinese adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc

RA conceptualized and designed the study, drafted and critically reviewed

the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. IF

Bekx MT, Connor EC, Allen DB. Characteristics of adolescents presenting to a

conceptualized and designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript,

multidisciplinary clinic for polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc

and approved the final manuscript as submitted. BD designed the study,

drafted and critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final

Gooding HC, Milliren C, St Paul M, Mansfield MJ, DiVasta A. Diagnosing

manuscript as submitted. EB conceptualized the study, designed the study,

dysglycemia in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Adolesc Health.

critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as

submitted. LT designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and

Flannery CA, Rackow B, Cong X, Duran E, Selen DJ, Burgert TS. Polycystic

approved the final manuscript as submitted. BN drafted and critically

ovary syndrome in adolescence: impaired glucose tolerance occurs across

reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

the spectrum of BMI. Pediatr Diabetes. 2013;14(1):42–9.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Palmert MR, Gordon CM, Kartashov AI, Legro RS, Emans SJ, Dunaif A.

Screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in adolescents with polycysticovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):1017–23.

Mani H, Levy MJ, Davies MJ, Morris DH, Gray LJ, Bankart J, et al. Diabetes

We would like to thank Mrs. Neera Bhatnagar, McMaster Health Sciences

and cardiovascular events in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a

Librarian for her invaluable assistance in refining the search strategy.

20-year retrospective cohort study. Clin Endocrinol. 2013;78(6):926–34.

Al Khalifah et al. Systematic Reviews (2015) 4:125

Hart R, Doherty DA. The potential implications of a PCOS diagnosis on a

Puhan MA, Schunemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. A GRADE working Group

woman's long-term health using data linkage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network

meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g5630.

Boomsma CM, Eijkemans MJ, Hughes EG, Visser GH, Fauser BC, Macklon NS.

Costello M, Shrestha B, Eden J, Sjoblom P, Johnson N. Insulin-sensitising

A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary

drugs versus the combined oral contraceptive pill for hirsutism, acne and

syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):673–83.

risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer in polycystic

Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ. Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast

ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;1:CD005552.

cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):748–58.

Shen CC, Yang AC, Hung JH, Hu LY, Tsai SJ. A nationwide population-basedretrospective cohort study of the risk of uterine, ovarian and breast cancerin women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Oncologist. 2015;20(1):45–9.

Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer amongwomen with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. GynecolOncol. 2015;136(1):99–103.

Jones GL, Hall JM, Lashen HL, Balen AH, Ledger WL. Health-related qualityof life among adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet GynecolNeonatal Nurs. 2011;40(5):577–88.

Crete J, Adamshick P. Managing polycystic ovary syndrome: what ourpatients are telling us. J Holist Nurs. 2011;29(4):256–66.

Nasiri Amiri F, Ramezani Tehrani F, Simbar M, Montazeri A, MohammadpourThamtan RA. The experience of women affected by polycystic ovary syndrome: aqualitative study from Iran. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12(2):e13612.

Conway G, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, et al. European survey ofdiagnosis and management of the polycystic ovary syndrome: results of theESE PCOS Special Interest Group's Questionnaire. Eur J Endocrinol.

2014;171(4):489–98.

Auble B, Elder D, Gross A, Hillman JB. Differences in the management ofadolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome across pediatric specialties.

J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26(4):234–8. Date of Publication: August2013.; 2013.

AlKhalifah R, Florez ID, Thabane L, Dennis B, Bassilious E. Metformin versusoral contraceptive pills for the management of polycystic ovarian syndromein adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPEROInternational prospective register of systematic reviews2015.

Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP. Demystifying trial networks and networkmeta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346:f2914.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols(PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj. 2015;349:g7647.

Sacks D; Canadian Paediatric Society. Age limits and adolescents. Paediatrics& Child Health. Nov 2003;8(9):577.

Search Filters for MEDLINE in Ovid Syntax and the PubMed translation.

2015.

Collaboration TC. The Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews ofinterventions version 5.1.0. 2011.

Guyatt G, Busse J. Commentary on tool to assess risk o f bias in cohortstudies.

Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis ofinconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):267–70.

Gelman A, Rubin DB. Inference from iterative simulation using multiplesequences. Stat Sci. 1992;7:457–72.

Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. StatMed. 2002;21(16):2313–24.

Higgins J. Identifying and addressing inconsistency in network meta-analysis.

Paper presented at: Cochrane comparing multiple interventions methodsgroup Oxford training event 2013.

Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Ades AE. Checking consistency in mixed

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2010;29(7–8):932–44.

and take full advantage of:

Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numericalsummaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an

• Convenient online submission

overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):163–71.

Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Adamopoulos E, Vedhara K. Mixed treatment

• Thorough peer review

comparison meta-analysis of complex interventions: psychological

• No space constraints or color figure charges

interventions in coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(9):1158–65.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE

• Immediate publication on acceptance

guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94.

• Research which is freely available for redistribution

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al.

GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence—indirectness. J ClinEpidemiol. 2011;64(12):1303–10.

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Source: http://old.systematicreviewsjournal.com/content/pdf/s13643-015-0105-4.pdf

Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease See separate articlesand The revised Joint British Societies' (JBS 3) guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in clinicalpractice recommend that CVD prevention should focus equally on the following three groups of patients who areat high risk of CVD: [1] Apparently healthy individuals with 20% or greater risk over 10 years of developing symptomaticatherosclerotic disease.People with diabetes mellitus (type 1 or 2).People with established atherosclerotic CVD.

CASE REPORT Intracerebral haemorrhage and We report on a 65-year-old woman who presented with acute right-sided weakness because of an intracerebral (thalamic) haemorrhage.As a Qigong enthusiast with a long-standing history of hypertension,she developed a stroke syndrome soon after practising Qigong onemorning. Following neurological recovery, the patient exhibited erraticblood pressure responses while practising Qigong, despite the factthat resting blood pressure was normal. The haemodynamic responsesto exercise are discussed and a review of the therapeutic implicationsof practising Qigong is presented.