Cs.rpi.edu

This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted

PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon.

Proteomics reveals multiple routes to the osteogenic phenotype in

mesenchymal stem cells

BMC Genomics 2007,

8:380

Kristin P Bennett ()

Charles Bergeron

Scott L Vandenberg ()

George E Plopper

Article type

Article URL

Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article was published immediately upon

acceptance. It can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright

notice below).

Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central.

For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to

2007 Bennett

et al., licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Proteomics reveals multiple routes to the osteogenic phenotype in mesenchymal

stem cells

Kristin P. Bennett1, Charles Bergeron1, Evrim Acar2, Robert F. Klees3, Scott L.

Vandenberg4, Bülent Yener2, and George E. Plopper3

1Department of Mathematical Sciences, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 110 8th Street,

Troy, NY 12180, USA

2Department of Computer Science, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 110 8th Street, Troy,

3Department of Biology, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 110 8th Street, Troy, NY

4Department of Computer Science, Siena College, 515 Loudon Road, Loudonville, NY

Email addresses:

[email protected] (K. Bennett),

[email protected] (C. Bergeron),

[email protected] (E. Acar),

[email protected] (R. Klees),

[email protected] (S.

Vandenberg),

[email protected] (B. Yener), and

[email protected] (G. Plopper)

Corresponding author:

Prof. Kristin P. Bennett, Ph.D.

Abstract

Recently, we demonstrated that human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC)

stimulated with dexamethazone undergo gene focusing during osteogenic differentiation

(

Stem Cells Dev 14(6): 1608-20, 2005). Here, we examine the protein expression profiles

of three additional populations of hMSC stimulated to undergo osteogenic differentiation

via either contact with pro-osteogenic extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (collagen I,

vitronectin, or laminin-5) or osteogenic media supplements (OS media). Specifically, we

annotate these four protein expression profiles, as well as profiles from naïve hMSC and

differentiated human osteoblasts (hOST), with known gene ontologies and analyze them

as a tensor with modes for the expressed proteins, gene ontologies, and stimulants.

Direct component analysis in the gene ontology space identifies three components

that account for 90% of the variance between hMSC, osteoblasts, and the four stimulated

hMSC populations. The directed component maps the differentiation stages of the

stimulated stem cell populations along the differentiation axis created by the difference in

the expression profiles of hMSC and hOST. Surprisingly, hMSC treated with ECM

proteins lie closer to osteoblasts than do hMSC treated with OS media. Additionally, the

second component demonstrates that proteomic profiles of collagen I- and vitronectin-

stimulated hMSC are distinct from those of OS-stimulated cells. A three-mode tensor

analysis reveals additional focus proteins critical for characterizing the phenotypic

variations between naïve hMSC, partially differentiated hMSC, and hOST.

The differences between the proteomic profiles of OS-stimulated hMSC and

ECM-hMSC characterize different transitional phenotypes en route to becoming

osteoblasts. This conclusion is arrived at via a three-mode tensor analysis validated using

hMSC plated on laminin-5.

Background

Interest in human stem cells continues to grow amongst those interested in

understanding fundamental mechanisms of development and disease progression and

those interested in harnessing the differentiation potential of these cells to generate living

replacements for damaged or diseased tissues. In both cases, the promise is the same:

stem cells offer the potential to define and manipulate fundamental principles of cell and

tissue behavior, which in turn will uncover a new set of therapeutic targets for correcting

errors in cell and tissue function [1]. Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) are a

population of multipotent adult cells found within the bone marrow and periosteum [2]

and capable of differentiating into as many as seven different cell types [3].

One bottleneck in the development of hMSC-derived therapies is our incomplete

understanding of the mechanisms governing hMSC differentiation. For example,

osteoblast differentiation from bone marrow progenitor cells (such as hMSC) has been

described as a series of up to seven overlapping stages, each defined by a change in gene

expression patterns [4]. Other studies suggest that these stages are a continuum, rather

than distinct events [5-7]. Further complicating matters, hMSC committed to an

osteogenic phenotype via treatment with dexamethazone retain the ability to

transdifferentiate into other lineages [8]. Distinct patterns defining osteogenic

differentiation of these cells have yet to emerge [9], though we and others have identified

significant signaling and gene expression changes during osteogenic differentiation of

To gain a better understanding of hMSC osteogenic differentiation, we previously

used gene ontology analysis of protein expression profiles from hMSC, human

osteoblasts (hOST), and hMSC stimulated to undergo osteogenic differentiation with

osteogenic stimulant (OS) media containing ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, β-

glycerophosphate, and the synthetic glucocorticoid, dexamethazone [15]. Our analysis

revealed that OS-induced differentiation results in a decrease

in the number of

mesenchymal cell markers and calcium-mediated signaling molecules with a concomitant

increase in expression of specific extracellular matrix molecules and their receptors, a

process we call "gene focusing." [15, 16] Second, we found that the protein expression

profile of OS-induced hMSC partially overlapped with the profiles of both naïve hMSC

and hOST, suggesting that OS-stimulated hMSC represent an "intermediate state" during

osteogenic differentiation of hMSC. These results strongly imply that changes in the

extracellular matrix (ECM) in the hMSC microenvironment have a direct impact on stem

cell differentiation.

It is well known that ECM proteins, along with growth factors and hormones,

play key roles during bone development. For example, during endochondral bone

development, collagen II expression peaks during the chondrogenesis period while

collagen I deposition is maximal during the ossification phase [17]. For decades it has

been known that single point mutations in collagen I yield a lethal form of osteogenesis

imperfecta (e.g., [18]). Genetic knockout of collagen II results in embryonic lethality

associated with severe skeletal defects [19]. In vitro, hMSC undergo osteogenic

differentiation when cultured on collagen I, fibronectin, vitronectin, or laminin-5 matrices

[11, 13, 20], and this requires ECM interaction with specific integrin receptors [11, 13,

21, 22]. A recent study demonstrates that osteogenic commitment of hMSC is irreversible

after three weeks in culture on collagen I [10] but osteogenic differentiation induced by

dexamethazone gradually diminishes in the absence of collagen I over the same time

course [9]. These results suggest that stimulation of hMSC with dexamethazone and

collagen I (or other ECM proteins) could induce osteogenic differentiation through

different mechanisms and that these differences could be detected in the protein profiles

of these different populations.

To test this idea, we used tensor analysis of protein expression profiles, annotated

with gene ontologies, to uncover protein expression changes during the progression of

stimulated hMSC towards fully differentiated hOST that distinguish distinct intermediary

states of OS-hMSC and ECM-hMSC. Our results support the conclusion that OS- and

ECM-induced hMSC are distinct intermediate states during osteogenic differentiation,

and demonstrate that stimulation with the ECM proteins collagen I, vitronectin, and

laminin-5 results in a more osteoblast-like phenotype than does stimulation with OS

To identify the proteins expressed by osteogenic differentiation of hMSC arising

from stimulation with OS media and two ECM proteins (collagen I and vitronectin) and

compare them to the protein expression profiles of undifferentiated hMSC; hMSC

stimulated by OS media; and physiologically differentiated hOST, we performed 2D LC-

MS/MS on whole-cell lysates of these cell populations. 758 distinct proteins indicated by

an Entrez gene ID (GeneID) were identified by 2D LC-MS/MS in all five cell

populations (≥200 pmol). To validate the approach, we also examined the expression of

these 758 distinct proteins in hMSC stimulated by laminim-5 (Ln-5). To evaluate the

functional significance of these differences, we accessed the GO (Gene Ontology) Chart

featured by DAVID to identify significant GO Biological Process and Molecular

Function categories for each of the 5 original samples and unioned them to form a set of

69 GO categories (provided in additional data file 1). Thus the data form a tensor or

datacube with three modes: the first being 6 experiments, the second being the 758

GeneIDs, and the third being the 69 GOs. Each entry of the tensor contains a 0 if no

proteins were found, 1 if exactly one protein was found, or 2 if multiple proteins were

found corresponding to a given (sample, GeneID, GO) triplet. We developed two-way

and three-way approaches for analyzing the (sample, geneID, GO) tensor. We begin with

discussion of the results of the two-way approach.

Two-way analysis

The two-way approach first reduces the three-mode tensor to a two-dimensional

matrix in the (sample, GO) space and then uses a variation of the widely-used Principal

Component Analysis (PCA) method in this space. Typically one would see PCA used

for genomics in the equivalent of the (sample, geneID) space. Traditional PCA centers

the data about the mean and then finds the series of orthogonal components that best

explain the variance of the data [23]. Our novel approach reduces the data to a

(sample,GO) matrix, transforms the data to make undifferentiated hMSC the origin, and

then directs or forces the first component to be the difference between hOST and hMSC

in the GO space. The remaining components are selected to maximize the explanation of

the remaining variability subject to the constraint that they be uncorrelated (orthogonal)

with each other and with the directed component. We call this approach to modeling

Directed Component Analysis (DCA), differing from

Principal Component Analysis in

that the offset and directed vectors are chosen based on biological process intuition as

opposed to the mean vector and leading principal component, respectively.

The GO proteomic profiles of each of the samples are projected onto the DCA

component space spanned by the first three components to provide clear insight into the

distinct states of the three types of sample. To validate the hypotheses that ECM

stimulated hMSC (ECM-hMSC) evoke similar intermediate differentiation states, we

reserve one of the ECM samples – hMSC stimulated with laminin-5 (ln5-hMSC) – as a

test sample. The components of DCA are constructed using only five samples: hMSC,

vintronectin stimulated hMSC (vn-hMSC), collagen 1 stimulated hMSC (col1-hMSC),

OS-hMSC, and hOST. The directed component accounts for 26% of the variability while

the second, third, and fourth components account for 41%, 22%, and 10% of the

variability, respectively, in the first five samples. The fourth component is largely noise

and thus is discarded. Thus each sample is transformed to a three dimensional

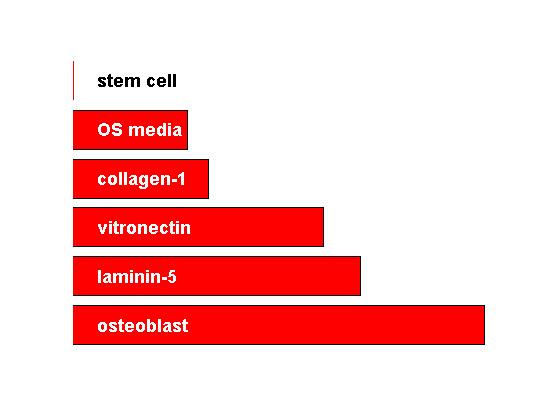

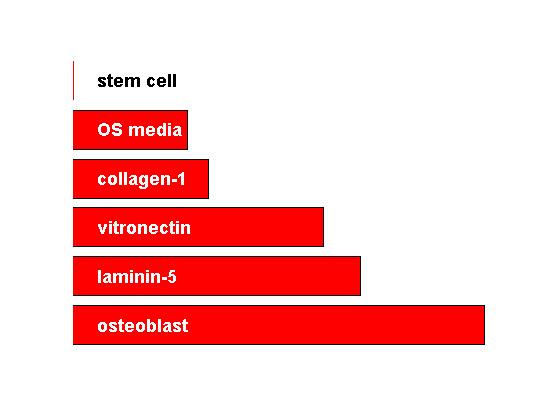

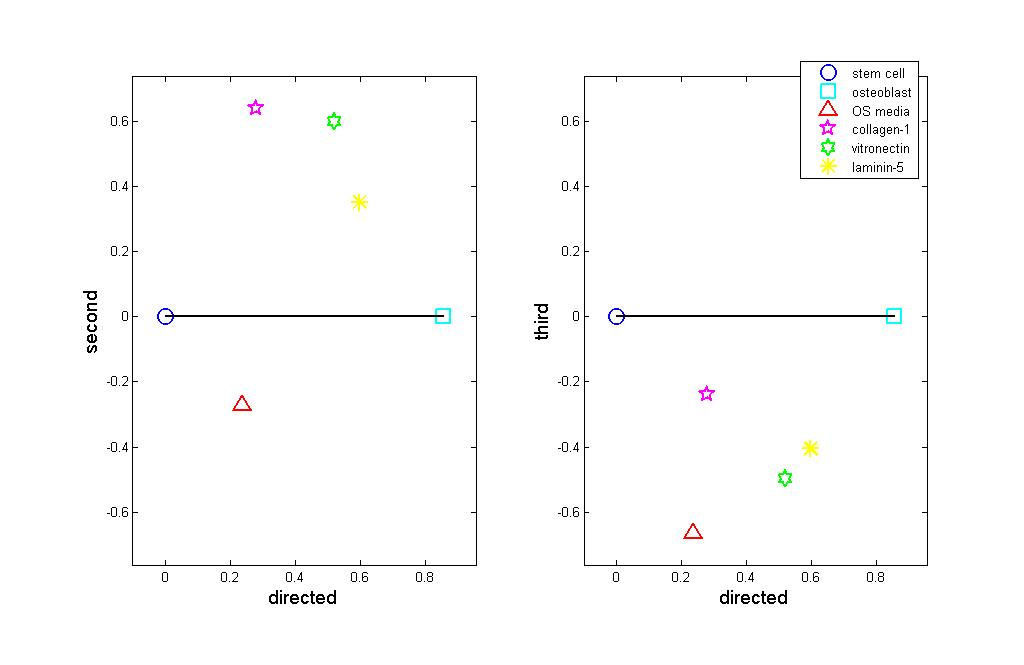

The first directed component is the direction that connects hMSC to hOST. For

each experiment,

c

is the extent to which the experiment is similar to osteoblast

along this route. These constants are plotted in Figure 1, providing an implicit ranking of

experiments. We can see that stimulated hMSC fall on a spectrum from hMSC to hOST.

We also see that the three ECM-stimulated samples cluster together including the

validation sample, ln5-hMSC, which was not used to construct the components. In

general the ECM-stimulated hMSC tend to more closely resemble osteoblasts than do the

OS media-stimulated hMSC. Thus, the first directed component provides a

characterization of how "osteoblast-like" the samples are. The two remaining

components capture how the samples vary from the directed path between hMSC and

hOST. The coefficients for each experiment may be plotted against each other, as in

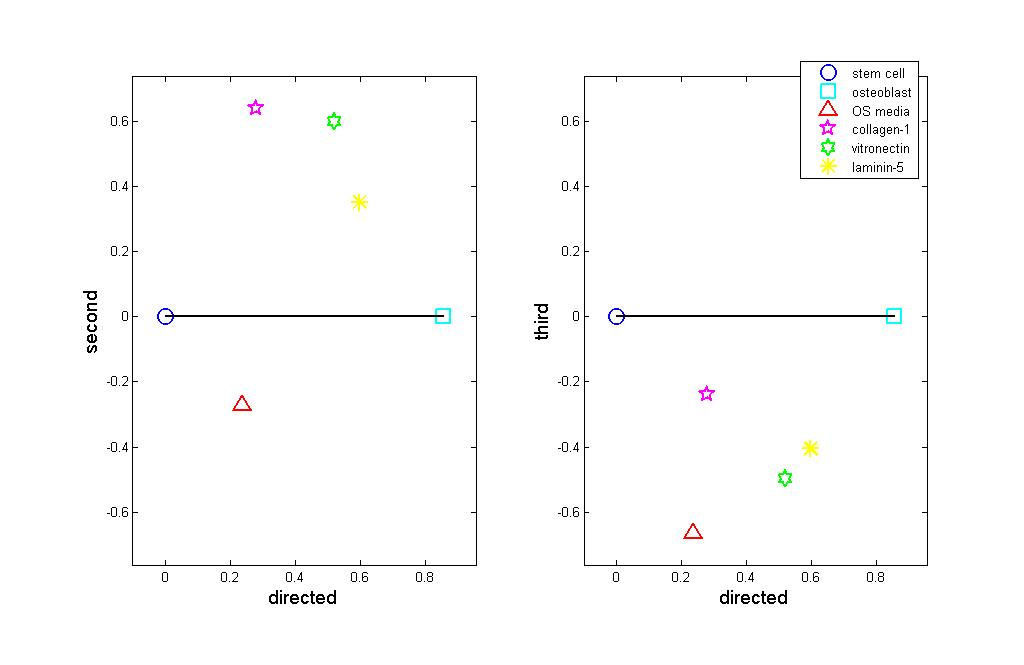

Figure 2. By construction of the directed component, the further right a population falls

the closer it is to hOST. The second component plotted as the vertical axis in Figure 2

(left) shows that ECM-hMSC and hOST-hMSC form two distinct intermediate states.

The ECM-hMSC cluster together at the top of the graph, meaning that they are fairly

similar in many respects. OS-hMSC appears at the bottom of the plot, far from the ECM-

hMSC samples.

The plot shows that the ECM-hMSC and OS-hMSC achieve distinct

intermediate states along the lineage from stem cells to Osteoblasts. Figure 2 (right)

plots the third component versus the directed component. Here we see that the stimulated

hMSC samples fall together and third component characterizes the variability within the

intermediate states. Together the plots suggest that the stimulated hMSC represent two

distinct lineages along the path from hMSC to hOST.

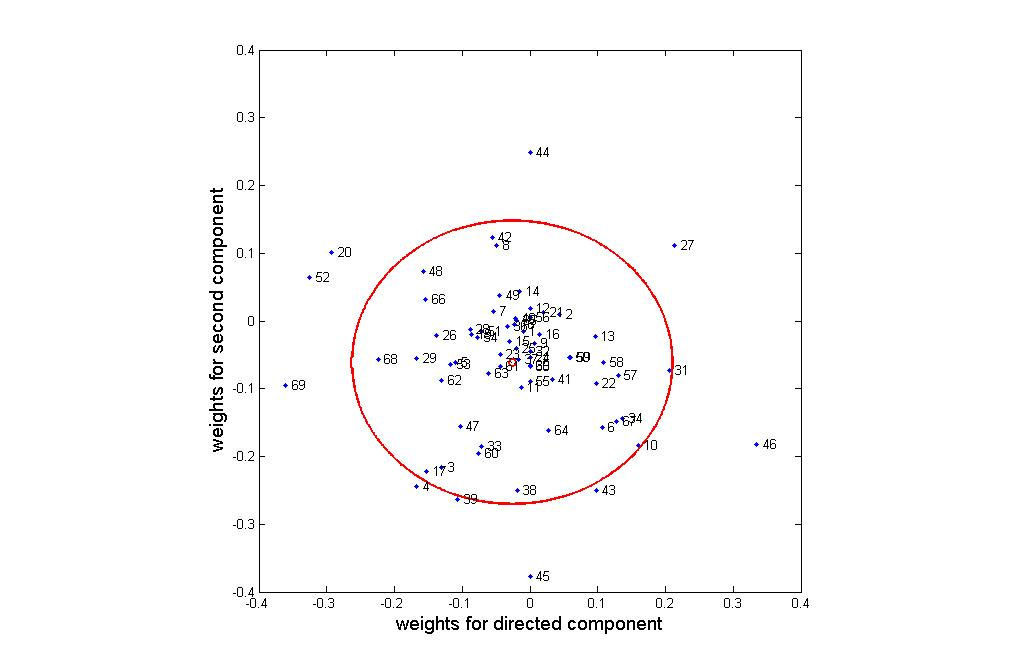

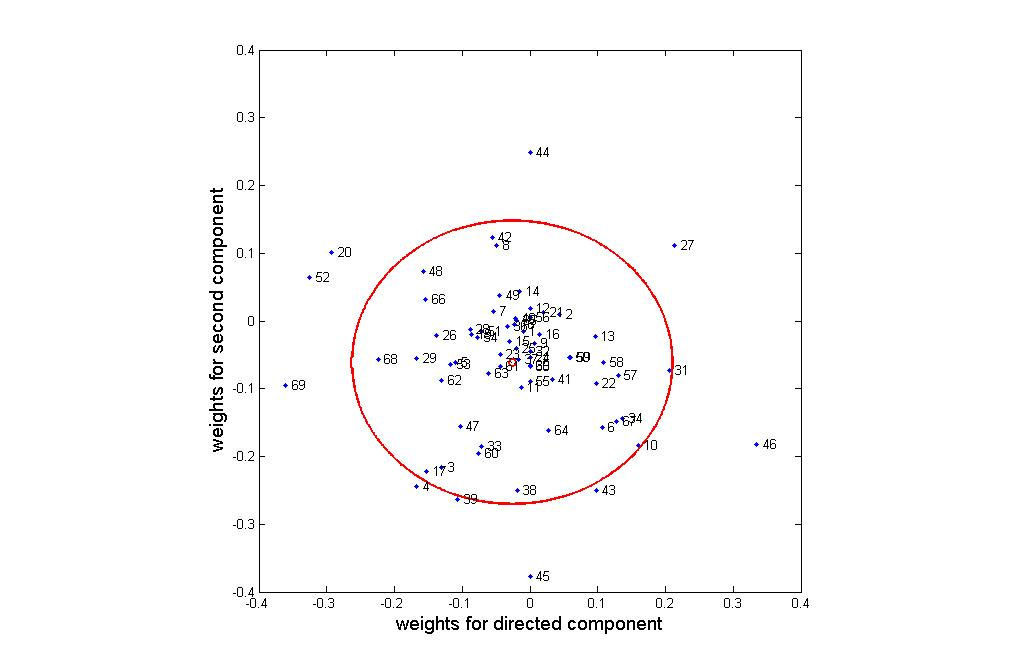

An interesting question is what categories have the greatest impact on the cell

differentiation process. Figure 3 plots weights for these categories in the directed and

second components plane. Categories near the center of the cluster (indicated by a small

red circle) have little impact on the experiments, while those far from the center (and in

particular outside of the circle of double standard deviation) are critical for osteogenesis.

From Figure 3, we can see that the following categories primarily characterize the

route from hMSC to hOST: 20 (cytokine activity), 27 (heparin binding), 46 (oxygen and

reactive oxygen species metabolism), 52 (protein kinase activity), and 69 (translation

initiation factor activity). The following categories primarily distinguish between the

OS- and ECM-stimulated intermediary states: 43 (oxidoreductase activity, acting on

peroxide as acceptor), 44 (oxidoreductase activity, acting on single donors with

incorporation of molecular oxygen), 45 (oxidoreductase activity, acting on the ch-ch

group of donors), categories 39 (organismal movement) and 4 ( amino acid and derivative

metabolism). Categories 52 (protein kinase activity) and 27 (heparin binding) are

important for characterizing both the transition from hMSC to hOST and the differences

between the two intermediate states. Repeating this analysis with the second and third

components identifies two additional GOs: 12 (cation transporter activity) and 42

(oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of

molecular oxygen). The proteins in this set of 12 GOs (given in additional data file 2,

Directed Component Analysis Spreadsheet) provide a set of potential biomarkers of

interest. Analysis of this set of proteins is provided in the discussion section.

Three-way analysis

In this section, our goal is to identify a set of significant GeneIDs and to capture

the structure within that set, taking into consideration in which categories and samples

they are present. While insightful for visualization and general trends, the two-way

analysis of the (Samples, GO) data involves a loss of information that limits the

information revealed regarding relevant GeneIds. The DCA analysis will miss critical

proteins that fall outside of the 13 categories identified. Multiway analysis fully

preserves the three-way nature of the data (GeneIDs, Categories, and Samples).

The Tucker3 [24] analysis was used to determine components for each of the

three modes: Sample, GeneID, and GO. The tensor was preprocessed in the same way as

in the two-way analysis: by truncating the number of proteins in each entry to at most

two and by transforming the data to make hMSC the origin. We make use of the results

provided by two-way analysis to determine the number of components to be extracted

from each mode in the Tucker3 model. Component numbers are chosen such that the

relationship observed in the sample mode coincides with the results of two-way analysis

of the Samples x Categories matrix. We select components in the Category mode that

best model the categories considered significant in capturing the structure in Samples

mode (those having high-loading coefficients). Then core elements are inspected in order

to identify the components in GeneID mode whose interaction with selected components

in other modes is represented with high core values. Finally, we examine the scatter plot

of the selected components (the first and third components have highest core value) in

GeneID mode to understand the structure among GeneIDs. Figure 4 illustrates GeneIDs

projected onto the space spanned by the first and third components of the GeneID mode.

We are particularly interested in the outliers detected through loading coefficients. A set

of 23 outlier GeneIDs, detected through both thresholding and statistical confidence

testing, is marked in Figure 4. A table containing these proteins can be found in

additional data file 3, Tensor Analysis Spreadsheet.

When we study the selected GeneIDs closely, we observe that two underlying

principles govern how they spread around the plot: Samples and Categories. For instance,

some outlier GeneIDs, e.g. {815, 816, 817, 818, 7170, 10342, 23043}, cluster together in

the first quadrant. That is because they not only exist in the same samples (mostly Sample

1 – hMSC) but also share significant categories, i.e. Protein Kinase Activity, Transferase

Activity, Transferring Phosphorus–containing Groups, etc. On the other hand, some

GeneIDs are farther apart from each other if they differ in either categories or samples

mode. For example, GeneIDs 529 and 539 are available in exactly the same categories

but they differ in the samples in which they are present. Therefore, one of them is in the

second quadrant while the other is in the fourth in Figure 4.

Discussion

Undifferentiated hMSC, ECM-hMSC, OS-hMSC, and fully differentiated hOST

express many proteins in common, yet each population also expresses distinct sets of

proteins. We believe these differences allow us to discriminate between different degrees

of osteogenic differentiation in hMSC, and suggest possible mechanisms for how

osteogenic differentiation occurs in these cells. To provide additional information to

offset the low sample size, we performed the analysis in the GO space. Our DCA

established a "differentiation axis" that allows us to rank and compare intermediate states

of osteogenic differentiation. This axis represents the vector accounting for the greatest

variance between hMSC and hOST and gives us a new tool to uncover protein/gene

expression differences that may be related to stem cell and osteoblast function. Tensor

analysis in the (sample, GO, GeneID) space was used to further elucidate proteins critical

for differentiation. Our approach is entirely different from, and complimentary to, more

traditional comparative methods such a DNA microarray, SAGE, and EST sequence

analysis [25-28]. The addition of gene ontology to the data tensor provides a critical

difference between our approach and the now standard Principal Component Analysis

(PCA) and more recent tensor analysis [29] for gene expression data.

Our differentiation axis begins with undifferentiated stem cells. The DCA and

tensor analyses identified at least 20 proteins expressed in undifferentiated hMSC, but not

in hOST, that may help define the activities of undifferentiated or partially differentiated

stem cells. Some of these, such as the eukaryotic translation factors (EIF2, EIF4, EIF5),

histone H4i, the lysosomal proteon pump ATP6V1E1, the peroxisomal biogenesis factor

6, asparagine synthetase, ER/Golgi transport (Rab1B), and chromobox homolog 3

participate in basic cellular activities and reflect the relatively generalized state of naïve

stem cells. Perhaps of greater interest are those proteins known to play a role in directing

activity of non-osteogenic cell types. For example, we identified several proteins that

have been linked with immune cell activation (e.g., carboxypeptidase N, SET

translocation, STAT1, CamK2G). And most interestingly, we see a number of signal

transduction proteins that help define undifferentiated stem cells in our data set. For

example, only unstimulated hMSC express TRAF2 and NCK interacting kinase, which

regulates actin cytoskeletal organization [30], and TRK-fused gene, which mediates

signaling through NF-κB in numerous cell types [31]. The most striking trend we see is

the presence of four calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 isoforms in hMSC but none

in hOST, consistent with our previous suggestion that calmodulin-based signaling is a

potential hallmark of undifferentiated hMSC [32]. Collectively, this expression profile

supports the notion that hMSC are more like "generic" cells than their differentiated

counterparts, though a functional definition of what constitutes a stem cell has yet to be

established [33].

At the opposite end of our axis are fully differentiated osteoblasts. We identified

13 proteins that are expressed in osteoblasts but not in stem cells and which our analyses

suggest contribute to the osteoblast phenotype. For some of these proteins, the connection

to osteoblast function is fairly clear: fibronectin is expressed in the matrix of developing

and mature bone and promotes the early stages of bone formation (e.g., [34]), and

vitronectin promotes osteogenic differentiation of hMSC [13]. Several isoforms of

dihydrodiol dehydrogenase, which metabolizes progesterone, are also found in hOST,

reflecting the importance of steroid hormones in skeletal growth and maintenance [35].

Others are less obvious – e.g., superoxide dismutase 1 and glutathione peroxidase 1,

which provide protection against oxidative stress, may serve an important maintenance

role during osteoblast differentiation. Also, peroxiredoxin 5 protects cartilage cells from

oxidative stress and maintains collagen synthesis [36] – perhaps these proteins perform a

similar function during collagen deposition by osteoblasts.

Along the middle of our axis lie the treated hMSC, and we think that these

represent intermediate states of osteogenic differentiation. Our analyses identified five

proteins that may distinguish these states from naïve stem cells or osteoblasts and may

uncover clues as to how osteogenic differentiation takes place in hMSC. Interestingly, the

heavy chain of smooth muscle myosin is in this group: recently, Discher's group

demonstrated that non-muscle myosin II mediates cell lineage specification in these cells

[10], suggesting that other myosins may play a role in determining cell lineage specificity

in response to ECM binding. Consistent with this hypothesis, filamin A is also found in

this group. Filamin A crosslinks cortical actin filaments, serves a mechanoprotective

function in response to tensile strain [37], and is controlled by calcium/calmodulin

signaling [38]. Because calcium/calmodulin signaling appears to decline during

osteogenesis in hMSC, filamin A activity may represent an early step towards lineage

commitment in these cells. Two other proteins that appear in all of our cell populations

(except hOST) may also serve as markers of an intermediate state: glucose phosphate

isomerase (also known as Autocrine Motility Factor) regulates cell growth and migration

of numerous cell types [39], and activin A receptor (type IIB) supports growth of germ

cells in the developing human embryo [40]. As stem cells are a continually self-renewing

population, whereas osteoblasts are much less proliferative, control of growth may be a

crucial step in moving away from the stem cell phenotype.

What is especially striking is that two different protein expression patterns occur

in these intermediates: that induced by contact with ECM proteins and that induced by

OS media. Our DCA identified three proteins that distinguish the ECM-directed route

from the OS-directed route, and all of these (two subunits of proline-4 hydroxylase and

lysine hydroxylase 2) are involved in collagen synthesis and processing. These proteins

are found in hOST and all ECM-treated populations, but not in OS, suggesting that

collagen synthesis in hMSC is preferentially driven by ECM contact. Consistent with

this, we and others have found that plating hMSC on collagen I stimulates additional

collagen synthesis [13, e.g., 41, 20]. Conversely, OS-treated hMSC express four proteins

involved in steroid metabolism (dihydrodiol dehydrogenase 1 and 2; 3-alpha

hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, type II; peroxisomal trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase) that

are not found in ECM-treated populations. Only two of these proteins appear in hOST.

Perhaps this is not surprising, since OS media contains the steroid analog dexamethazone,

but it illustrates an important point: hMSC can be stimulated to undergo osteogenic

differentiation by two seemingly independent routes – one driven by ECM signaling and

one by steroid hormone signaling.

Conclusions

Our three-mode tensor-based proteomic analysis, based on gene ontologies and

validated using hMSC plated on laminin-5, has revealed two independent mechanisms by

which human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) undergo osteogenic differentiation. The

differences between the proteomic profiles of OS-stimulated hMSC and ECM-hMSC

characterize different transitional phenotypes en route to becoming osteoblasts. One of

these is driven by ECM signaling and the other by steroid hormone signaling. In

addition, stimulation with ECM proteins results in a more osteoblast-like phenotype than

that resulting from stimulation with OS media. These results, arrived at through

interdisciplinary means, contribute to a better understanding of osteogenesis and thus, we

hope, eventually to improved treatment for relevant diseases and tissue damage.

Bovine collagen I and vitronectin were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula,

CA). All other reagents and cell culture supplies were obtained as previously described

[15, 16]. Protein profiles from hMSC, hMSC cultured in OS medium, and hOST were

accessed from our online database described in [11].

Culture of hMSC

Cryopreserved hMSC were routinely passaged as previously described [11]. To

collect protein expression profiles from hMSC stimulated with ECM proteins, cells were

grown in hMSC growth media in tissue culture dishes coated with 20 µg/ml collagen I or

20 µg/ml vitronectin, or grown on tissue culture dishes containing laminin-5 deposited by

804G rat bladder carcinoma cells as previously described [16].

2D LC-MS/MS

Preparation of whole cell lysates (collected after 16 days in culture) from hMSC

cultured on ECM proteins for 2D LC-MS/MS was performed as previously described

[11]. Briefly, protein pellets were dissolved in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 5 mM tributyl

phosphine, and 6.4 M urea. The protein mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C

followed by the alkylation in 15 mM iodoacetamide. Reactants were then diluted six-fold

and subjected to tryptic digestion overnight at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with the

addition of 90% formic acid, and the resultant peptides were then concentrated with C18

cartridges and exchanged into 5% acetonitrile, 0.4% formic acid, and 0.005%

heptafluorobutylic acid (HFBA). Samples (120 µg protein) were analyzed in duplicate

using an analytical system consisting of a CapLC autosampler, CapLC pumps, stream

selector, Z-spray probe, and a quadruple time-of-flight mass (TOF) spectrometer. The

setup was configured with a polysulfoethyl strong cation exchange (SCX) column (320

µm ID X 80 mm, packed with 20 µm POROS 20 HS from Applied Biosystems) in series

with a desalting column (300 µm ID X 5 mm, packed with a C18 stationary phase from

Thermo Quest Inc.) and a reverse-phase C18 column (75 µm ID X 110 mm, packed with

BetaBasic C18 resin from ThermoHypersil Keystone) for two-dimensional separations.

For elution, solvent A9 consisted of 3% CH3CN, 0.4% acetic acid, and 0.005% HFBA;

solvent B was 90% CH3CN, 0.4% acetic acid, and 0.005% HFBA. Tryptic digests were

loaded onto the 2D LC-MS/MS system under pressure. Peptides in 10 mM NaCl solution

were first absorbed onto the SCX column; the peptides in the flow through were washed

onto the reverse-phase peptide-trapping column where they were concentrated and

desalted. First-stage separation was achieved by eluting the SCX column with 20 µl each

of 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 120, 140, 150, 160, 200, 250, 300, 500, and

830 mM KCl. For second-stage separation, each of the eluates was separated on a

reverse-phase column by the application of a series of mobile phase-B gradients (1–10%

B in 5 min, 10–15% B in 25 min, 15–20% B in 15 min, 20–45% B in 10 min, 45–80% B

in 5 min). The separated peptides were characterized by their mass and sequence data

(MS/MS). To load samples, a picofrit column was connected directly to a Q-TOF 2

Zsprayer. Approximately 2,100 volts were applied to the spray tip. Approximately 5 psi

of nebulizing gas was introduced around the spray tip to aid the electrospray process. A

splitter gave a resultant flow through the analytical column of 200 nl/min with the pump

programmed to deliver a flow of 6.5 µl/min. The mass spectrometer was operated in a

data-dependent acquisition mode whereby, following the interrogation of MS data, ions

were selected for MS/MS analysis based on their intensity and charge state. The detection

threshold for this instrument is 200 pmol per protein. Collision energies were chosen

automatically based on the m/a and charge-state of the selected precursor ions. Ion data

were compared to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

nonredundant homo sapiens database using the Proteinlynx 1.1 Global Server program.

Data Preparation

945 different proteins were identified by 2D LC MS/MS; 765 different proteins

were identified with accession numbers (in Ensemble, Refseq, or Trembl format) and a

protein name.

Each protein was also matched to its GeneID at NCBI [42], if available,

by accessing the European Bioinformatics Institute [43], downloading the

ipi.HUMAN.xrefs.gz IPI dataset [44], and matching each accession number to its

corresponding gene ID number. Proteins that were not assigned a GeneID using this

method were searched by hand using the online search function (IPI Quick Search) and

the search feature located at Entrez Gene by entering available accession numbers and the

protein name.

A given protein as identified by the GeneID may have multiple accession

numbers. The number of accession numbers per protein was truncated to 2. Since

laminin-5 hMSC proteomic analysis was used as validation, only GeneIDs found in the

first five samples were considered. There are 555 such GeneIDs, corresponding to 758

To determine protein functional relationships within and between each data set,

we used the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID)

[45] to annotate proteins identified by GeneID with their gene ontologies. The GeneIDs

of proteins in the six samples were categorized in Biological Process and Molecular

Function gene ontology categories using the GO Chart feature offered by DAVID 1.0

with settings of intermediate coverage and specificity (Level 3) with a minimum of 4

GeneIDs as done in [15,16]. The GO categories were determined for each data set and

then unioned to form a complete list. DAVID was set at intermediate coverage and

specificity (Level 3) with a minimum of 4 GeneIDs. The 69 GO categories used in this

study are given in additional data file 1.

A relational database management system (DBMS) was used to develop both the

gene ontology analysis and the further protein classifications. Reports and queries were

written and generated, using the DBMS facilities and additional programming, to help

produce the statistics reported in this paper and to help produce the 3-dimensional

Proteomics Array described next.

Each entry in the three-way Proteomics Array, Xijk, represents the number of

accession identifiers observed for the ith protein available in the jth category for the kth

sample. We apply several preprocessing steps compatible with those of two-way analysis.

First, proteins that are available in all samples and the ones that do not exist in any of the

samples are removed. The dimension of X is 361 x 69 x 5 after the elimination of these

proteins. Second, each entry is truncated to 0, 1, or 2. For the two-way model, we first

add the data across the GeneID mode to form a Sample x Category matrix, then divide

each GO vector by its sum, and finally center the data by subtracting the hMSC vector.

For the multi-way model, we center the data with respect to hMSC, which means that the

slice or matrix corresponding to hMSC is subtracted from the slices corresponding to

other samples. Note that as validation, the two-way and multi-way analyses are

performed using only the first five samples and then the results for laminim-5 hMSC are

projected onto the components defined by the first five cell populations.

Two-way analysis: Directed Component Model

Consider matrix X consisting of 69 categories as rows and 5 features

(experiments) as columns. Call each column xj so that X=[x1 x2 x3 x4 x5]. Each entry Xij

represents the active proteins in category i found in experiment j. We seek a linear model

for the xj as follows:

x =

d

The vectors

d are directions that make up the columns of X and the scalars

c are distances

in these directions. Each direction is now discussed in turn.

To begin, the first direction is the starting point for osteogenesis, that is, stem

cells. Hence

d

=

x , which is hMSC. Next, we are interested in the direction that

connects stem cells to osteoblasts. Hence

d

=

x −

x , which hOST less hMSC. For

each experiment,

c

is the extent to which that experiment is similar to osteoblasts

along this route. These constants were plotted in Figure 1, providing an implicit ranking

of experiments. We see that the three ECM-stimulated populations are closer to

osteoblasts than are the OS media-stimulated populations.

The remaining directions {

d

are chosen such as to maximize the

remaining variability subject to being uncorrelated (perpendicular) with the previous

directions. That is, these directions are the principal components of the remaining space.

The constants thereof {

c

indicate how far away from the direct path

linking stem cell to osteoblast an experiment is. The directed component accounts for

26% of the variability while the second, third, and fourth components account for

41%, 22%, and 10% of the variability respectively in the first five experiments.

Multi-way analysis: Tucker3 Model

We model the three-way Proteomics Array, X ∈

R IxJxK, as in Equation 1, using a

Tucker3 [24] model, which is one of the most common analysis techniques in the multi-

= ∑ ∑ ∑

G A B C +

E (Eq. 1)

Here P, Q, and R indicate the number of components extracted from the sample, geneID,

and GO modes, respectively. A ∈

R IxP, B ∈

R JxQ, and C ∈

R KxR are orthogonal

component matrices. G ∈

R PxQxR is the core array and E ∈

R IxJxK represents the error

term. A Tucker3 model with orthogonality constraints on component matrices is also

called Higher-Order Singular Value Decomposition (HOSVD) [46]. Figure 5 illustrates

the three-way Proteomics Array and how it is modeled using a Tucker3 model. In our

analysis, we make use of the PLS Toolbox [47] and for detailed information on the

Tucker3 model and other multiway analysis techniques, the reader is referred to [48].

List of Abbreviations

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC)

osteogenic stimulant (OS)

human osteoblasts (hOST)

Entrez gene ID (GeneID)

GO (Gene Ontology)

ECM stimulated hMSC (ECM-hMSC)

Directed Component Analysis

(DCA)

Authors' Contributions

KB, BY, and GP conceived the study and drafted portions of the manuscript. CB

prepared and analyzed data. EA and BY carried out the tensor analysis. RK and GP

created the cultures and carried out the 2D LC-MS/MS. KB and SV acquired, prepared,

and analyzed data. SV also drafted part of the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

This work was supported by Grant #1R01EB002197 from the National Institutes of Health (GP).

References

1. Le Blanc K, Pittenger M:

Mesenchymal stem cells: progress toward promise.

Cytotherapy 2005,

7:36-45.

2. Barry FP, Murphy JM:

Mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications and

biological characterization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004,

36:568-584.

3. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman

MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR:

Multilineage potential of adult

human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999,

284:143-147.

4. Aubin JE:

Advances in the osteoblast lineage. Biochem Cell Biol 1998,

76:899-

5. Smith E, Redman RA, Logg CR, Coetzee GA, Kasahara N, Frenkel B:

Glucocorticoids inhibit developmental stage-specific osteoblast cell cycle.

Dissociation of cyclin A-cyclin-dependent kinase 2 from E2F4-p130 complexes. J Biol Chem 2000,

275:19992-20001.

6. Hou Z, Nguyen Q, Frenkel B, Nilsson SK, Milne M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL,

Quesenberry P, Lian JB, Stein GS:

Osteoblast-specific gene expression after

transplantation of marrow cells: implications for skeletal gene therapy. Proc

Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999,

96:7294-7299.

7. Ryoo HM, Hoffmann HM, Beumer T, Frenkel B, Towler DA, Stein GS, Stein JL,

van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB:

Stage-specific expression of Dlx-5 during osteoblast

differentiation: involvement in regulation of osteocalcin gene expression. Mol

Endocrinol 1997,

11:1681-1694.

8. Song L, Tuan RS:

Transdifferentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem

cells derived from bone marrow. FASEB J 2004,

18:980-982.

9. Song L, Webb NE, Song Y, Tuan RS:

Identification and functional analysis of

candidate genes regulating mesenchymal stem cell self-renewal and

multipotency. Stem Cells 2006,

24:1707-1718.

10. Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE:

Matrix elasticity directs stem cell

lineage specification. Cell 2006,

126:677-689.

11. Klees RF, Salasznyk RM, Kingsley K, Williams WA, Boskey A, Plopper GE:

Laminin-5 induces osteogenic gene expression in human mesenchymal stem

cells through an ERK dependent pathway. Mol Biol Cell 2005,

16:881-890.

12. Salasznyk RM, Klees RF, Hughlock MK, Plopper GE:

ERK signaling pathways

regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on

collagen I and vitronectin. Cell Commun Adhes 2004,

11:137-153.

13. Salasznyk RM, Williams WA, Boskey A, Batorsky A, Plopper GE:

Adhesion to

Vitronectin and Collagen I Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Human

Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J Biomed Biotechnol 2004,

2004:24-34.

14. Xiao G, Gopalakrishnan R, Jiang D, Reith E, Benson MD, Franceschi RT:

Bone

morphogenetic proteins, extracellular matrix, and mitogen-activated protein

kinase signaling pathways are required for osteoblast-specific gene expression

and differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 2002,

17:101-110.

15. Salasznyk RM, Klees RF, Vandenberg S, Bennett K, Plopper GE:

Gene focusing

as a basis for controlling stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells Dev 2005,

14:608-

620.

16. Klees RF, Salasznyk RM, Vandenberg S, Bennett K, Plopper GE:

Laminin-5

activates extracellular matrix production and osteogenic gene focusing in

human mesenchymal stem cells. Matrix Biol 2007,

26:106-114.

17. Bortell R, Barone LM, Tassinari MS, Lian JB, Stein GS:

Gene expression during

endochondral bone development: evidence for coordinate expression of

transforming growth factor beta 1 and collagen type I. J Cell Biochem 1990,

44:81-91.

18. Pace JM, Chitayat D, Atkinson M, Wilcox WR, Schwarze U, Byers PH:

A single

amino acid substitution (D1441Y) in the carboxyl-terminal propeptide of the

proalpha1(I) chain of type I collagen results in a lethal variant of osteogenesis

imperfecta with features of dense bone diseases. J Med Genet 2002,

39:23-29.

19. Aszodi A, Bateman JF, Gustafsson E, Boot-Handford R, Fassler R:

Mammalian

skeletogenesis and extracellular matrix: what can we learn from knockout

mice? Cell Struct Funct 2000,

25:73-84.

20. Cool SM, Nurcombe V:

Substrate induction of osteogenesis from marrow-

derived mesenchymal precursors. Stem Cells Dev 2005,

14:632-642.

21. Mizuno M, Kuboki Y:

Osteoblast-related gene expression of bone marrow cells

during the osteoblastic differentiation induced by type I collagen. J Biochem

(Tokyo) 2001,

129:133-138.

22. Xiao G, Wang D, Benson MD, Karsenty G, Franceschi, RT:

Role of the alpha2-

integrin in osteoblast-specific gene expression and activation of the Osf2

transcription factor. J Biol Chem 1998,

273:32988-32994.

23. Wall ME, Rechtsteiner A, Rocha LM:

Singular Value Decomposition and

Principal Component Analysis. In

A Practical Approach to Microarray Data

Analysis. Edited by Berrar DP, Dubitzky W, Granzow M. Norwell MA: Kluwer;

2003:91-109.

24. Tucker LR:

Some mathematical notes on three-mode factor analysis.

Psychometrika 1966,

31:279-311.

25. Hayman MW, Christie VB, Keating TS, Przyborski SA:

Following the

differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells by proteomic identification of

biomarkers. Stem Cells Dev 2006,

15:221-231.

26. Shi S, Robey PG, Gronthos S:

Comparison of human dental pulp and bone

marrow stromal stem cells by cDNA microarray analysis. Bone 2001,

29:532-

539.

27. Tremain N, Korkko J, Ibberson D, Kopen GC, DiGirolamo C, Phinney DG:

MicroSAGE analysis of 2,353 expressed genes in a single cell-derived colony of

undifferentiated human mesenchymal stem cells reveals mRNAs of multiple

cell lineages. Stem Cells 2001,

19:408-418.

28. Jia L, Young MF, Powell J, Yang L, Ho NC, Hotchkiss R, Robey PG, Francomano,

CA:

Gene expression profile of human bone marrow stromal cells: high-

throughput expressed sequence tag sequencing analysis. Genomics 2002,

79:7-

17.

29. Alter O, Golub GH:

Reconstructing the pathways of a cellular system from

genome-scale signals by using matrix and tensor computations. Proc Natl Acad

Sci U S A 2005,

102:17559-17564.

30. Fu CA, Shen M, Huang BC, Lasaga J, Payan DG, Luo Y:

TNIK, a novel member

of the germinal center kinase family that activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase

pathway and regulates the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 1999,

274:30729-30737.

31. Matsuda A, Suzuki Y, Honda G, Muramatsu S, Matsuzaki O, Nagano Y, Doi T,

Shimotohno K, Harada T, Nishida E, Hayashi H, Sugano S:

Large-scale

identification and characterization of human genes that activate NF-kappaB

and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene 2003,

22:3307-3318.

32. Salasznyk RM, Westcott AM, Klees RF, Ward DF, Xiang Z, Vandenberg S,

Bennett K, Plopper GE:

Comparing the protein expression profiles of human

mesenchymal stem cells and human osteoblasts using gene ontologies. Stem

Cells Dev 2005,

14:354-366.

33. Parker GC, Anastassova-Kristeva M, Eisenberg LM, Rao MS, Williams MA,

Sanberg PR, English D:

Stem cells: shibboleths of development, part II:

Toward a functional definition. Stem Cells Dev 2005,

14:463-469.

34. Tang CH, Yang RS, Huang TH, Liu SH, Fu WM :

Enhancement of fibronectin

fibrillogenesis and bone formation by basic fibroblast growth factor via

protein kinase C-dependent pathway in rat osteoblasts. Mol Pharmacol 2004,

66:440-449.

35. Liang M, Liao EY, Xu X, Luo XH, Xiao XH:

Effects of progesterone and 18-

methyl levonorgestrel on osteoblastic cells. Endocr Res 2003,

29:483-501.

36. Yuan J, Murrell GA, Trickett A, Landtmeters M, Knoops B, Wang MX:

Overexpression of antioxidant enzyme peroxiredoxin 5 protects human tendon

cells against apoptosis and loss of cellular function during oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004,

1693:37-45.

37. Kainulainen T, Pender A, D'Addario M, Feng Y, Lekic P, McCulloch CA:

Cell

death and mechanoprotection by filamin a in connective tissues after challenge

by applied tensile forces. J Biol Chem 2002,

277:21998-22009.

38. Nakamura F, Hartwig JH, Stossel TP, Szymanski PT:

Ca2+ and calmodulin

regulate the binding of filamin A to actin filaments. J Biol Chem 2005,

280:32426-32433.

39. Tsutsumi S, Yanagawa T, Shimura T, Fukumori T, Hogan V, Kuwano H, Raz A:

Regulation of cell proliferation by autocrine motility factor/phosphoglucose

isomerase signaling. J Biol Chem 2003,

278:32165-32172.

40. Martins da Silva SJ, Bayne RA, Cambray N, Hartley PS, McNeilly AS, Anderson,

RA:

Expression of activin subunits and receptors in the developing human

ovary: activin A promotes germ cell survival and proliferation before

primordial follicle formation. Dev Biol 2004,

266:334-345.

41. Williams WA, Schapiro NE, Christy SR, Weber GL, Salasznyk RM, Plopper GE:

Diminished Gene Expression in human Mesenchymal Stem Cells by Mutation

of Focal Adhesion Kinase Signaling. J Stem Cells 2006,

1:173-182.

42.

Entrez Gene [http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene]

43.

International Protein Index [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/IPI/IPIhelp.html]

44.

International Protein Index Current Datasets

45.

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

46. De Lathauwer L, De Moor B, Vandewall JA:

A multilinear Singular Value

Decomposition. SIAM J Matrix Anal Appl 2000,

21:1253-1278.

47.

Eigenvector Research, PLS Toolbox [http://software.eigenvector.com/#pls]

48. Smilde AK, Bro R, Geladi P:

Multi-way Analysis with Applications in the

Chemical Sciences. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2004.

Figure Legends

Figure 1. Directed Component scores. The directed component score ranks the

samples (experiments) from stem cells to osteoblasts.

Figure 2. Directed Component plots of hMSC, hOST, and stimulated stem cells.

Directed Component plots of hMSC, hOST, and stimulated stem cells demonstrate

distinct lineages of ECM-hMSC vs. OS-hMSC.

Figure 3. Weights on the GOs for the directed and second components. Weights on

the GOs are plotted for the directed and second components. GOs falling outside the

circle of standard deviation are critical for the components.

Figure 4. Scatter plot of GeneIDs. 361 GeneIDs are projected onto the space spanned

by the first and third components in GeneID mode. Red color and diamond shape are

used to indicate the GeneIDs considered significant and examined closely. The rest of the

GeneIDs have comparatively low loading coefficients and areconsidered insignificant.

Figure 5. Three-way Proteomics Array and Tucker3 Model. Proteomics Array with

GeneID, Category, and Sample modes is modeled with [P Q R] – Tucker3 model. A, B,

and C are component matrices corresponding to GeneID, Category, and Sample modes,

respectively. G is the core array and E contains the residuals for each entry in X.

Description of additional data files

Additional file 1:

File name: Supp1

File format: Word

Title: The 69 GO (Gene Ontology) categories used in this study, listed alphabetically

Additional file 2:

File name: Supp2

File format: Excel

Title: Directed Component Analysis Data

Description: Gene ontologies, GeneIDs, symbols, names, and distinct protein counts for

the six samples (hMSC, OS-hMSC, col-hMSC, FN-hMSC, hOST, and LN5-hMSC).

Additional file 3:

File name: Supp3

File format: Excel

Title: Tensor Analysis Data

Description: Contains outliers detected by choosing the GeneIDs outside the 95%

confidence ellipse. Each GeneID is accompanied by its symbol, name, and the counts of

distinct proteins found in the six samples (hMSC, OS-hMSC, col-hMSC, FN-hMSC,

hOST, and LN5-hMSC).

B

Additional files provided with this submission:

Additional file 1: supp1.doc, 22KAdditional file 2: supp2.xls, 30KAdditional file 3: supp3.xls, 19K

Source: http://www.cs.rpi.edu/~yener/PAPERS/BIO/BMCGenomics2007.pdf

Bundestierärztekammer e. V. Französische Straße 53, 10117 Berlin, Tel. 030/2014338‐0, [email protected], www.bundestieraerztekammer.de Die Betäubung muss in tierärztlicher Hand bleiben Im Rahmen der begrüßenswerten Diskussion um die Abschaffung von betäubungslosen Eingriffen an Tieren ist beabsichtigt, dass Landwirte nicht nur den Eingriff, sondern auch die Betäubung aus Kostengründen selbst durchführen dürfen. Bisher ist nach § 5 Abs. 1 Satz 2 des Tierschutzgesetzes die Betäubung von schmerzhaften Eingriffen von einem Tierarzt durchzuführen. Die Änderung des Tierschutzgesetzes sieht nun vor, dass Tierhalter eine ab dem Jahr 2019 vorgeschriebene Betäubung für den Schenkelbrand und die Kastration von Ferkeln selbst durchführen dürfen. Der am 13. Dezember im Bundestag zur Abstimmung stehende Wortlaut des Gesetzes ist aus Sicht der Tierärzteschaft nicht geeignet, eine Verbesserung des Tierschutzes herbeizuführen. Im Gegenteil, der Tierschutz wird gefährdet. Außerdem sind die Vorschriften widersprüchlich und aus fachlicher Sicht unrealistisch. Wir fordern, auf diese schmerzhaften und chirurgischen Eingriffe ganz zu verzichten und die Betäubung in tierärztlicher Hand zu belassen. Andernfalls soll zumindest im § 5 Abs. 1 nach Satz 4 der Satz ergänzt werden: „Dies gilt nicht für Lokalanästhetika". Damit würde verhindert, dass Mittel mit Missbrauchspotenzial und Nebenwirkungen in die Hände von Laien gelangen. Wir fordern, dass im Rahmen der Verordnung nach § 6 Abs. 6 (Ferkelkastration) darauf hingewirkt wird, dass noch zu entwickelnde Mittel, die für die Schmerzausschaltung bei der Ferkelkastration dem Landwirt ausgehändigt werden dürfen, praktikabel angewendet werden können und innerhalb von weniger als einer Minute wirken. Andernfalls würde die „Betäubung" eine Verbrauchertäuschung darstellen. Da die Wirkung nur kurzzeitig anhält, muss zusätzlich die Anwendung von Mitteln, die den postoperativen Schmerz lindern, vorgeschrieben werden. Das gilt auch für den Schenkelbrand. Die Abgabe von Mitteln zum Zweck der Schmerzausschaltung an den Landwirt ist auf Anwendungsgebiete zu beschränken, die aus zwingenden organisatorischen und wirtschaftlichen Gründen vom Tierhalter durchgeführt werden müssen. Begründung: 1. Verfügbare Arzneimittel Nach dem Wortlaut von § 5 Abs. 1 soll es sich um für diesen Zweck zugelassene Tierarzneimittel handeln. Diese sind derzeit nicht vorhanden. Zum Schenkelbrand: Ein Mittel, das äußerlich angewendet wird und den Schmerz bei einer Verbrennung dritten Grades ausschaltet, ist derzeit nicht vorhanden. Zur Ferkelkastration: NSAID wie Meloxicam, das schon jetzt zur Linderung postoperativer Schmerzen beim Schwein zugelassen ist, können den Operationsschmerz nicht ausschalten, wie es das Gesetz verlangt. Lokalanästhetika, die bisher verfügbar sind, wirken erst nach einigen Minuten, sodass der Kastrationsvorgang bei der üblichen Vorgehensweise (ohne Wartezeit) ohne Betäubung erfolgen würde. Außerdem lindern diese Mittel den postoperativen Schmerz nicht.

[ RESIDENT'S CASE PROBLEM ] MICHAEL S. CROWELL, PT, DPT¹����DEHC7D�M$�=?BB" PT, DSC, OCS, FAAOMPT² Medical Screening and Evacuation: Cauda Equina Syndrome in a Combat Zone Low back pain (LBP) is a prevalent condition, particularly in cific LBP, nerve root syndrome (radicu- primary care clinics, with billions of dollars spent each year