Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Gastroentérologie Clinique et Biologique (2009) xxx, xxx—xxx

Vous êtes

autorisé à consulter ce document mais vous ne devez en aucun cas le télécharger ou l'imprimer.

Operative risks of digestive surgery in

cirrhotic patients

Risque opératoire du patient cirrhotique en chirurgie digestive

R. Douard , C. Lentschener , Y. Ozier , B. Dousset

a Service de chirurgie digestive et endocrinienne, hôpital Cochin, Assistance publique—Hôpitaux de Paris,faculté de médecine Paris Descartes, 27, rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques, 75014 Paris, Franceb Service d'anesthésie—réanimation, hôpital Cochin, Assistance publique—Hôpitaux de Paris,faculté de médecine Paris-Descartes, 27, rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques, 75014 Paris, France

Digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients has long been limited to the treatment of dis-

orders related to the liver disease (portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma and umbilicalhernia). The improvement in cirrhotic patient management has allowed an increase in surgicalprocedures for extrahepatic indications. The aim of this study was to evaluate the operativerisks of such surgical procedures. Extrahepatic surgery in cirrhotic patients is associated withhigh mortality and morbidity. Emergency surgery, gastrointestinal tract opening (esophagus,stomach and colon), < 30 g/L serum albumin, transaminase levels more than three times theupper limit of normal, ascites, and intraoperative transfusions are the main risk factors forpostoperative death. In Child A patients, the operative risk of elective surgery is moderate andsurgical indications are not altered by the presence of cirrhosis. The laparoscopic approachshould be recommended because of the potentially lower morbidity. In Child C patients, oper-ative mortality is often higher than 40%; surgical indications must remain exceptional and nonoperative management has to be preferred. In Child B patients, preoperative improvement ofliver function is mandatory for lower risk surgery.

2009 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

La chirurgie digestive chez le cirrhotique a longtemps été limitée au traitement

des conséquences de la maladie hépatique (hypertension portale, carcinome hépatocellulaire,hernie ombilicale). L'amélioration de la prise en charge des cirrhotiques a permis une aug-mentation du nombre d'interventions réalisées pour des indications extrahépatiques. Le butde ce travail a été de faire le point sur le risque opératoire du cirrhotique dans ces indica-tions chirurgicales. La chirurgie extrahépatique chez le patient cirrhotique est associée à destaux élevés de mortalité et de morbidité élevés. Une intervention en urgence, une interven-tion portant sur le tube digestif (œsophage, estomac, côlon), une hypoalbuminémie inférieure à30 g/L, des transaminases supérieures à trois fois la limite supérieure de la normale, la présence

∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: (B. Dousset).

0399-8320/$ – see front matter 2009 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009), doi:

ARTICLE IN PRESS

R. Douard et al.

d'une ascite et l'existence de transfusions peropératoires sont les principaux facteurs de risquede mortalité postopératoire. Chez les malades Child A, le risque opératoire en chirurgie élec-tive est modéré et les indications chirurgicales ne sont pas modifiées par la cirrhose. La voied'abord laparoscopique doit être privilégiée car elle pourrait diminuer la morbidité. Chez lesmalades Child C, la mortalité opératoire dépasse souvent 40 % ; les indications chirurgicalesdoivent rester exceptionnelles et il faut privilégier les traitements non opératoires. Pour lesmalades Child B, il faut différer l'intervention et améliorer la fonction hépatique pour diminuerle risque opératoire.

2009 Elsevier Masson SAS. Tous droits réservés.

Digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients has long been limitedto the treatment of disorders related to the liver disease;portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma and umbili-cal hernia. Improvement in cirrhotic patient managementhas improved patient survival and so more and more cir-rhotic patients are proposed for surgery. In this population,the number of surgical procedures for extrahepatic diseasehas consequently increased in a similar proportion. Althoughpostoperative morbidity and mortality are higher than gen-erally observed, few studies have examined the specific risksof digestive surgery in the cirrhotic patient. The purposeof this study was to review our knowledge of the opera-tive risk of digestive surgery in the cirrhotic patient. Theoperative risk related to hepatic surgery and portal hyper-tension will not be discussed in this review because they aredirectly related to the liver disease and its consequences.

We will first discuss the overall operative risk in the cir-rhotic patient and then examine the specific consequencesof surgery in this population before analyzing the different

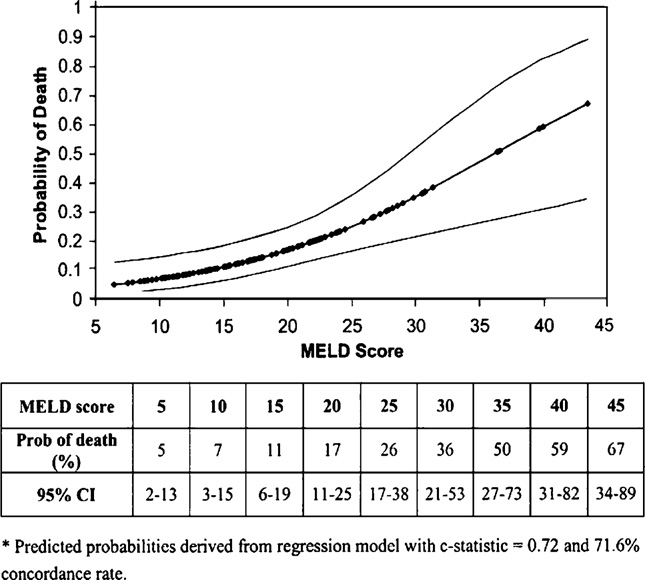

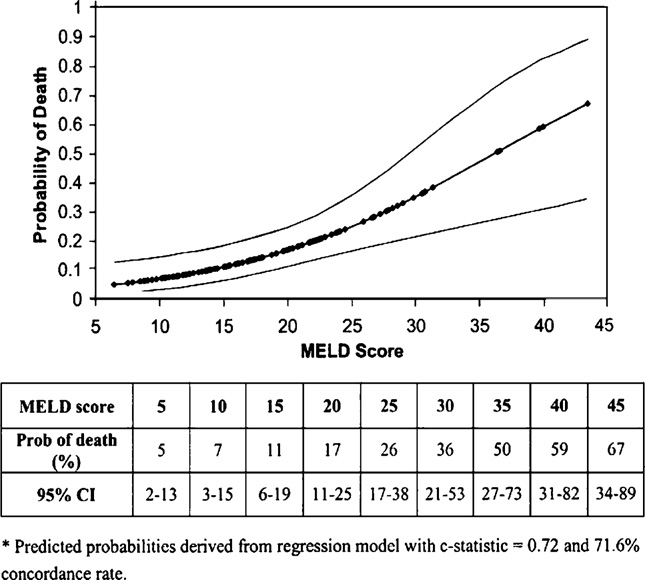

From Northup et al. mortality rate in the

types of surgery individually.

140 study cirrhotic patients at 30-day follow-up after generalsurgery according to the model for end-stage liver disease(MELD) score. The MELD score takes into account the inter-

Surgical risk in the cirrhotic patient

national normalized ratio, total bilirubin and serum creatininelevel.

Operative mortality in the cirrhotic patient is correlatedwith the severity of liver failure, irrespective of the scoreused to assess surgical risk The Child-Pugh (

cirrhotic patient undergoing general surgery procedures

and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores

Operative risk is higher in patients with sev-

initially correlated with operative mortality for portal caval

eral factors The risk of postoperative death, even for a

anastomosis, can be transposed to general operative risk

major operation, in cirrhotic patients free of ascites, liver

for cirrhotic patients. More recently, Ziser et al. confirmed

failure and acute alcoholic hepatitis, and who have a normal

these data and identified eight factors significantly corre-

prothrombin level, is the same as observed in noncirrhotic

lated with postoperative morbidity and mortality in the

patients with the same pathological condition

Organ failure in the operated cirrhotic patient

Child-Pugh classification

Hemodynamics

Irrespective of the etiology, cirrhotic patients present a

hyperkinetic hemodynamic situation associating elevated

heart flow rate, low systemic blood pressure and low left

Serum bilirubin (mol/L)

ventricle afterload associated with splanchnic vasodilata-

Serum albumin (g/L)

tion This splanchnic vasodilation ‘‘steals'' vascular flow

from other vital territories such as the renal circulation

The Child-Pugh score is the sum of points (5—15). The Child-Pugh

Perioperative infusion of vasopressive amines may be

stage is established from the Child-Pugh score: A: 5 or 6 points;

necessary to counterbalance the loss of volumetric con-

B: 7—9 points; C: 10—15 points. For primary biliary cirrhosis, the

trol triggered by the surgery. Perioperative hemodynamic

points for serum bilirubin are as follows: 1 point for <70 mol/L,

variations may disclose an alcohol-related dilated cardiomy-

2 points for 70 to 170 mol/L and 3 points for >170 mol/L.

opathy (low cardiac output and/or rythm disorders) or

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009),

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Digestive surgery and cirrhosis

Factors associated with postoperative complication in cirrhotic patients

Mortality at 30 days (%)

Mortality at 6 months (%)

Child-Pugh score: 7—10

Elevated serum creatinine

Chronic respiratory disease

Preoperative infection

Upper digestive bleeding

Low interoperative blood pressure

Cryptogenetic cirrhosis

cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (left ventricular dysfunction)

effective A deficit in factors I, II, V, VII, IX, X due to

Pulmonary artery hypertension, defined as a mean pul-

defective hepatic synthesis is correlated with the severity

monary arterial pressure ≥ 25 mmHg, associated with a

of liver failure. Apparently primary fibrinolysis is usually

normal wedge pressure can coexist with cirrhosis. The risk

a complication, especially of infection. Hypercoagulation

is severe intra- and postoperative heart failure due to right

markers are common in patients with cirrhosis, who are

ventricle failure. The prevalence of coronary artery disease

susceptible to thromboembolic complications

is high in the cirrhotic population, where diabetes, alcoholabuse and smoking are common

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is a common finding in cirrhotic patients

and is correlated with the severity of liver failure. Dex-

Hypoxemia has been noted in 15 to 45% of cirrhotic patients

trose infusions may reveal deficiency in trace elements and

generally related to pleural effusion associated with

vitamins Today, clinicians consider that cirrhosis does

ascites The hepatopulmonary syndrome is defined by

not preclude renutrition but have been unable to formally

hypoxemia associated with an oxygen alveolar-arterial gra-

demonstrate an advantage in terms of postoperative mor-

dient without cardiac anomalies. The causal mechanism is

the shunt provoked by the dilation of the pulmonary precap-illary arterioles. A spontaneous ventilation hyperoxemia test

Infections in the operated cirrhotic patient

can be used to assess the correction of the hypoxemia and

Preexisting infection is an independent variable associated

quantify the shunt, predictive of postventilatory weaning

with postoperative morbidity (74%) and mortality at 30 days

and postoperative respiratory tolerance

(49%) and 6 months (60%) in the operated cirrhotic patientSystematic search for infection and preoperative treat-

Renal function and ascites

ment are thus mandatory in the cirrhotic patient. Cirrhosis is

Renal blood flow declines proportionally with the sever-

not an independent factor for operative site infection, irre-

ity of the cirrhosis-related hyperkinetic syndrome In

spective of the type of surgery (contaminated or not)

patients with liver failure, lean body mass is often dimin-

It is, however, a risk factor for infections distant from the

ished and glomerular filtation can be greatly reduced despite

operative site Consequently, the same antibiotic pro-

a normal serum creatinine level Serum levels must be

phylaxis must be scheduled for the cirrhotic patient as for

assayed repeatedly in cirrhotic patients receiving nephro-

the noncirrhotic patient with the same surgical risk

toxic drugs In a surgery context, blood or digestive

steady rise in medicalization of cirrhotic patients has led

fluid losses, constitution of a third sector, evacuation of

to a high prevalence of multiresistant germs, irrespective

abundant ascites, aggressive diuretic treatment and inap-

of the site of infection Nasal and rectal swabs might

propriate fluid and electrolyte restriction may aggravate the

be helpful in detecting carriers of multiresistant bacteria

impact of the hyperkinetic syndrome on the kidneys inducing

among previously medicalized cirrhotic patients In the

functional renal failure Ascites is a frequent compli-

cirrhotic patient, the frequency of postoperative infections

cation of abdominal surgery in the cirrhotic patient

is associated with translocation of gastrointestinal tract

The ascitic fluid arises via a diminution of the circulating

bacteria into the general blood stream, blood transfusion,

volume There is no evidence supporting the hypothesis

duration of surgery, severity of liver failure and insufficient

that postoperative restriction of fluid intake prevents post-

antibiotic therapy Preoperative decontamination

operative ascites There is no evidence that exsudative

of the digestive tract has not been found to decrease the

effusion associated with digestive resection and postopera-

rate of postoperative infections

tive chylous ascites are specific for this population

Quantitative changes in the synthesis of binding proteins cir-

Splenic sequestration of platelets leads to various degrees

culating in the blood stream leads to an increase in the

of thrombopenia. Circulating platelets are functionally

concentration of pharmacologically active free fraction of

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009), doi:

ARTICLE IN PRESS

R. Douard et al.

certain drugs, including antibiotics The distribution vol-

fat-free diet supplemented with medium chain triglycerides

ume of certain drugs can be increased as a result of fluid

may be insufficient. Drainage (or iterative puncture) may

and electrolyte retention Drug administration must be

be needed, combined with exclusive parenteral nutrition to

halt the production of this chylous ascites in 4 to 6 weeks.

Anesthesia and postoperative analgesia

No anesthesia protocol has been proven superior in the

Renal failure is observed in nearly 10% of operated cir-

operated cirrhotic patient Locoregional and peridural

rhotic patients may present functional renal failure

anesthesia and analgesia should be discussed for patients

a hepatorenal syndrome associated with severe liver

with normal coagulation factors and a platelet count above

failure renal failure subsequent to acute tubular

100,000/mm3 who would not be expected to develop

necrosis related to severe infection or multiorgan failure. It

major fibrinolysis postoperatively. Acetaminophen should be

is associated with ascites in 60% of patients and an infectious

used prudently Nefopam is not submitted to hepatic

syndrome in 50%. These associations show that the renal

metabolism; its efficacy in relieving postoperative pain has

failure is generally the consequence of other complications

been demonstrated for major digestive surgery Care-

(dehydration, infection, multiorgan failure).

ful titration of analgesic and secondary effects is requiredfor morphine prescription Inhibition of prostaglandin

synthesis in the kidneys by administration of nonsteroidal

Postoperative infection affects 13 to 40% of operated

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) is a cause of renal ischemia

cirrhotic patients The rate is higher if the gas-

by reduced blood flow NSAID should be proscribed for

trointestinal tract has been opened In the cirrhotic

cirrhotic patients with ascites

patient, infections occur more readily late after surgery andgenerally do not involve the operative site. The most com-

Chronic viral hepatitis B and C

mon localizations include the lung (8%) and the urinary tract

Viral disease can be associated with renal failure,

or infected ascites, sometimes associated with septicemia

systemic hypertension, pulmonary vasculitis, cryoglobu-

The risk of spontaneous bacteriemia is higher

linemia, peripheral neuropathy, thyroid dysfunction and

in cirrhotic patients and increases further in the event of

thrombopenic purpura. The secondary effects of certain

postoperative liver failure

antiviral agents should be taken into account, e.g. epilep-sia, depression, leukothrombopenia with infection and risk

Complications involving the abdominal wall

of hemolysis with ribavirin

Ascites leakage through the abdominal wall is observedin 2% of operated patients, even if abdominal drainage is

Specific postoperative complications

installed. This leakage favors infections and evisceration.

Abdominal drainage may be insufficient to avoid this leakage

but significantly increases the risk of ascites infection

Postoperative ascites is one of the main complications

Abdominal drainage can, however, avoid excessive accu-

observed in cirrhotic patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

mulation of ascites which would exaggerate the leakage

The prevalence is greater than 20% The risk of post-

favoring the constitution of pseudocellulitis due to infiltra-

operative ascites is significantly increased by the presence

tion of the subcutaneous tissues and evisceration.

of intraoperative ascites and installation of drainage. The

An expert consensus recommends a solid suture of the

risk differs depending on the type of abdominal surgery;

abdominal wall using a slow resorbing thread and tight clo-

it is lower after parietal and biliary surgery. Postoperative

sure of the teguments using a cutaneous overcast stitch.

ascites in a cirrhotic patient can be divided into three cat-

Depending on the procedure performed and the anticipated

egories. Type I is correlated with liver failure. It is favored

risk of postoperative ascites, it is recommended either to

by postoperative fluid and electrolyte retention and readily

avoid drainage or to drain with a sterile aspiration system.

responds to treatment. Type II ascites is defined as unremit-ting and difficult to treat. More commonly observed after

supramesocolonic surgery (gastrectomy), this type of ascites

This complication is observed in 10% of operated cirrhotic

would be related to section of the lymphatic vessels drain-

patients but in only 5% of those undergoing abdominal

ing the liver and overloaded with interstitial fluid because of

surgery Because of this high rate special pre- and

the portal hypertension This is a lymphatic ascites of

postoperative measures are warranted to prevent digestive

hepatic origin producing a clear effusion with high protein

bleeding related to portal hypertension, i.e. betablockers

content, high lymphocyte count and a normal triglyceride

and/or endoscopic treatment, depending on the size of

level, similar to the ascites observed after liver transplanta-

the varices and the past history of rupture of esophageal

tion Type III postoperative ascites is a chylous effusion

varices In the cirrhotic patient, there is a higher risk of

related to the extravasation of lymphatic fluid rich in

bleeding from gastroduodenal stress ulcers; favoring factors

triglycerides arising from the interruption of the mesenteric

are severe sepsis, prolonged mechanical ventilation, liver

lymphatic flow because of the surgical section of the mesen-

failure and abdominal surgery Several studies have

teric or periaortic lymphatic vessels It can be observed

demonstrated an increased risk of nosocomial pneumopathy

after pancreatic, colonic or small bowel surgery. There is no

related to the use of antisecretory agents (compared with

relationship between the severity of the liver failure and

sucralfate) by alkalinization and colonization of the gastric

the development of chylous ascites. Treatment is difficult;

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009),

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Digestive surgery and cirrhosis

Severe liver failure

umbilical hernia and 2% after elective surgery Mortality

Severe liver failure is the most common complication, the

was zero in the two most recent studies reported by expert

cause of nearly 50% of postoperative deaths

centers and including 39 and 40 patients undergoing surgery

For the majority of patients, severe liver failure develops in

for umbilical hernia

a context of preoperative liver failure after an emergencyintervention opening the gastrointestinal tract. Prothrombin

below 50% and total serum bilirubin > 50 mol/L on the 5th

Surgery should be proposed solely for

postoperative day would be the best sign of postoperative

inguinal hernias and incisional hernia which become symp-

liver failure This 50-50 rule was defined for patients

tomatic or complicated. For patients with a moderately

undergoing liver resection of healthy or pathological liv-

altered liver function (Child A or B), cure for inguinal her-

ers but not for patients undergoing extrahepatic surgery.

nia can be achieved with acceptable morbidity In

It is difficult to differentiate liver failure from multiorgan

the presence of ascites, the same precautions must be taken

failure, common in this context.

as for umbilical hernias. The French Association of Surgeryreported a series of 38 inguinal hernias (one case of prosthe-

Surgery of the abdominal wall

sis interposition) and 23 incisional hernias (nine prosthesisinterpositions and two peritoneojugular shunts) Mor-

Hernias and incisional hernias are more common in the cir-

tality was 5.7% (91% elective surgery). The recurrence rate

rhotic patient than in the general population. Abdominal

was 8 to 10% recurrence being favored by weak wall

distention caused by the ascites and the loss of muscle mass

structure and ascites.

secondary to the poor nutritional status are the main risk

Irrespective of the type of parietal hernia or evisceration,

factors In the cirrhotic patient, the rate of abdominal

an extraperitoneal interposition prosthesis should be used in

wall hernia is 16% and reaches 24% in the presence of ascites

cirrhotic patients because of the higher risk of recurrence.

More than half of all hernias are umbilical; the

Furthermore, prostheses with a very low infectious risk are

rate is 4-fold higher in patients with ascites. Umbilical her-

available. This approach is however debatable if the patient

nias are also favored by Cruveilhier-Baumgarten syndrome

presents a complication (strangulation, rupture), cutaneous

(renewed patency of the umbilical vein). Treatments for

lesions or an infected ascites. If the ascites proves to be

inguinal hernia and incisional hernia must be distinguished

unresponsive to treatment, a TIPS would probably be the

from the treatment of umbilical hernia more specific to the

best solution since indications for peritoneojugular shunt

cirrhotic patient.

have disappeared. Should a cirrhotic patient on the livertransplantation list present a hernia or incisional hernia freeof complications, treatment may be delayed until the trans-

plantation procedure, although a TIPS while on the waiting

Indications retained for treating an umbilical hernia are

list might be useful to prevent the development of parietal

functional impairment and presence of a complication:

voluminous herniation, strangulation, rupture, cutaneous

The operative technique should prefer oblique or

lesions. Strangulation, rare in patients with ascites, is

transversal approaches, using a multilayer wall closure with

favored by a sudden drop in the volume of the effusion due to

slow resorption thread and overcast stitches to limit the risk

an umbilical rupture, evacuating puncture, vigorous medical

of ascites leakage and evisceration. If possible, drainage

treatment or installation of a peritoneojugular shunt

should be avoided, but when necessary, using a minimally

The goal is to treat the ascites before undertaking surgery.

traumatic technique with sterile aspiration. There is no con-

Specific complications after surgical treatment of an umbil-

traindication for laparoscopy in a cirrhotic patient

ical hernia are ascites, renal failure, wall infection, liverfailure and recurrent hernia. Ascitis is the main cause ofrecurrent parietal deficiency; 71% versus 4% without ascites

The predominant role of ascites in the developmentof postoperative complications explains why a simultane-

ous peritoneojugular shunt has been proposed in the event

Biliary surgery in cirrhotic patients is mainly represented

of refractory ascites or when an emergency treatment is

by gallstone. Incidence is increased because of the hyper-

required, despite the estimated 14% risk of infection

splenism and the subsequent hemolysis. Prevalence of

More recently, a small series of three cirrhotic patients who

gallstones in the cirrhotic patient is higher than in the gen-

underwent emergency surgery for a ruptured or strangu-

eral population, reaching 17 to 28% Cirrhosis, with

lated umbilical hernia reported treatment by parietal repair

cardiovascular disease, is the main risk factor for postchole-

and installation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

cystectomy mortality. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated

shunt (TIPS) on days 2, 0 and 2 of the herniorrhaphy

that, on average, cholecystectomy is performed in cirrhotic

These data, based on the efficacy of TIPS for the treat-

patients in more urgent situations and with higher morbidity

ment of refractory ascites suggest that TIPS should be

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is currently the pre-

preferred over peritoneojugular shunt for the treatment of

ferred technique for cirrhotic patients Complications

umbilical hernia in patients with refractory ascites.

include ascites, liver failure, infection, kidney failure, diges-

In the series reported by the French Association of

tive bleeding and operative site bleeding. Morbidity is

Surgery, which included 81 patients who underwent surgical

related to the indication, the severity of the liver fail-

treatment of an umbilical hernia, overall mortality was 5%:

ure, blood transfusion and surgical approach. There were

11% after emergency surgery for ruptured or strangulated

no deaths in a study comparing the results of laparoscopic

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009), doi:

ARTICLE IN PRESS

R. Douard et al.

cholecystectomy (n = 26) with open cholecystectomy (n = 24)

of 52 cirrhotic patients who underwent endoscopic sphinc-

in Child A or B patients The conversion rate for

terotomy for common bile duct stones Considering this

the laparoscopic procedures was 12%, with significantly

evidence, several teams have proposed balloon endoscopic

decreased morbidity (19% versus 67%, p = 0.001) and lower

sphincteroclasia to avoid the risk of bleeding in cirrhotic

risk of transfusion (0% versus 33%, p = 0.008) Laparo-

patients, particularly Child C patients

scopic cholecystectomy in Child A or B patients is feasible

For the Child A or B patient, stones in the common

with a conversion rate of 5 to 9%, 5 to 10% morbidity

bile duct should be treated by endoscopic sphinctero-

and 0 to 1% mortality In the cirrhotic patient,

tomy followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Endoscopic

laparoscopy is associated, as in the noncirrhotic patient,

sphincteroclasia would appear to be the best alternative for

with less blood loss, shorter operative time and shorter hos-

Child C patients, without secondary cholecystectomy.

pital stay Some authors suggested that in thecirrhotic patient preoperative coagulation disorders would

be more predictive of difficult operation and complicationsfor laparoscopic cholecystectomy than the Child score. Oth-

Excepting the survey published by the French Association of

ers have proposed subtotal cholecystectomy in this

Surgery data are lacking on the specificity of pancre-

context of increased risk of hemorrhage, especially for acute

atic surgery in the cirrhotic patient. In the published series,

or chronic cholecystitis. On the contrary, for the Child C

35 patients underwent surgery for chronic (n = 17) or acute

patient, cholecystectomy is associated with a prohibitive

(n = 3) pancreatitis, a malignant tumor (n = 14) or a benign

death rate of 23 to 50% severe liver failure, acute

tumor (n = 1). The procedures were resection (n = 9; left

cholecystitis and emergency surgery are common in this

pancreatectomy: 3, pancreaticoduodenectomy: 2, ampul-

type of patient. Most authors agree that medical treat-

lectomy: 2, atypical resection for acute pancreatitis: 2) and

ment should be proposed in this type of situation. If the

derivations (n = 26; digestive = 7, biliodigestive: 13, pancre-

medical approach is unsuccessful, or should pyocholecystitis

aticodigestive: 10). The transfusion rate was 44%, morbidity

develop, percutaneous cholecystostomy could be a solution

51% and mortality 20%. All three patients who had an emer-

The cholecystotomy should ideally be performed via

gency procedure died. All deaths occurred in patients whose

a transhepatic approach after transfusion of platelets and

gastrointestinal tract was opened. The univariate analysis

coagulation factors; percutaneous drainage of the ascites

identified emergency procedure and elevated transaminase

may be associated or precede the operation.

level as independently predictive of death.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the procedure of choice

The findings suggest endoscopic (stent, endoscopic cys-

for the Child A or B patient with symptomatic gallstones or

togastrostomy, ampullectomy) and radiologic (percutaneous

acute cholecystitis morbidity is 10 to 15%, mortality 0

drainage of pancreatic abscesses) treatments should be pre-

to 1% and conversion rate 5 to 9%. For the Child C patient,

ferred in cirrhotic patients with an inflammatory disease or

medical treatment should be proposed and, if necessary,

tumor of the pancreas. The rare indications for resection

combined with percutaneous cholecystostomy.

should be reserved for elective procedures in Child-Pugh Apatients without elevated transaminases.

Common bile duct stones

Treatment of stones in the common bile duct is more diffi-

cult in the cirrhotic patient because the procedure involves

cholecystectomy and extraction of the stone from the bileduct. Stone extraction is difficult because of the portal

Studies on gastric surgery in the cirrhotic patient have

hypertension and the risk of injuring neighboring varices or

focused on the treatment of complications of peptic ulcers

triggering hemobilia with the extraction instruments. In the

and gastric cancers.

series reported by the French Association of Surgery, morbid-

Peptic ulcers appear to be more common in cirrhotic

ity in 31 patients undergoing surgery for a common bile duct

patients, affecting 8 to 20% of patients The propor-

stone was 29%, with 9.6% mortality. In a series of 87 cirrhotic

tion of cirrhotic patients among patients with peptic ulcer

patients who underwent surgery for gallstones (n = 53) or

appears to be higher than the equivalent proportion in the

common bile duct stones (n = 34), morbidity was 15% and

general population: 9% among patients with hemorrhagic

mortality 4.5%. Two factors had a significant impact on mor-

ulcer, 6% among patients with a perforated ulcer and 8%

bidity and mortality: Child-Pugh stage C (morbidity 32%,

among patients aged 65 years-old and over with a symp-

mortality 12%) and presence of a stone in the common duct

tomatic ulcer The mortality of emergency surgery for

(morbidity 24%, mortality 9%) Another team compared

complicated peptic ulcer in the cirrhotic patient is very

surgery (n = 9) versus endoscopic sphincterotomy (n = 7) for

high, ranging from 23 to 64% Prognostic fac-

this indication. Mortality was 44% versus 14.3% (p < 0.01) and

tors impacting mortality are severity of the liver failure and

morbidity 66% versus 14% (p < 0.01) with a mean blood loss

presence of ascitis With the advent of proton

of 1576 mL after surgery highlighting the benefits for endo-

pump inhibitors, eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the

scopic sphincterotomy Another study confirmed these

development of endoscopic hemostasis techniques, the effi-

findings and reported 67% morbidity after surgery versus 22%

cacy of simple suture of the perforation in a patient with

after endoscopic sphincterotomy with no significant differ-

peritonitis due to the perforated ulcer has been demon-

ence for mortality Endoscopic sphincterotomy has thus

strated, dramatically reducing the indications for surgery

become the gold standard for common bile duct stones, fol-

and gastric resections for hemorrhagic ulcers. Excepting rare

lowed by elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The risks

cases, emergency surgery for complicated ulcers does not

must not however be overlooked; mortality was 7% in a series

require resection, although the gastrointestinal tract must

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009),

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Digestive surgery and cirrhosis

be opened. Two controlled studies have demonstrated the

• pleural effusion (26%);

efficacy of laparoscopic suture of perforated ulcers

• anastomotic fistula (24%);

by extrapolation, laparoscopic suture of perforated ulcers

• infection (22%);

can be proposed for cirrhotic patients.

• renal failure (17%).

Two series from Japan have reported results of surgi-

cal treatment of gastric cancer in cirrhotic patients. The

Twelve patients (26%) died. Factors predictive of fatal

first was a series of 37 operated patients (24 superficial can-

outcome included liver failure (prothombin < 60%, serum

cers); morbidity was 20%, mortality 0%, and 5-year actuarial

albumin < 30 g/L, serum bilirubin > 35 mol/L), transfusion

survival 51% The second study included 39 operated

of more than three packed cell units and anastomotic fis-

patients (28 superficial cancers); morbidity was 26%, mortal-

tula. These findings illustrate the risks of esophagectomy in

ity 10.3% and 5-year acturarial survival 64% for superficial

the cirrhotic patient; mortality is greater than 20% and the

cancers and 14% for invasive cancers Causes of late

rate of anastomotic leakage greater than 20%. This surgery

death were mainly related to the liver disease.

should be reserved for Child-Pugh A5 patients with T1-T3 N0

The series of 66 operated cirrhotic patients with gas-

tumors who are free of ascites and transaminase elevation.

tric disease reported by the French Association of Surgery

For all other patients, non-surgical treatment with exclusive

included patients with a noncomplicated benign disease

chemoradiotherapy should be proposed

(n = 12), hemorrhagic or perforated ulcer (n = 35), malignanttumor (n = 17) or another disease (n = 2). Mortality was 23%,

significantly higher in patients with ascites and low serumalbumin; mortality was not affected by gastric disease orby type of surgery (simple suture, vagotomy, gastrectomy).

Particularities of colorectal cancer in the cirrhotic

Overall morbidity was 56%, most deaths related to ascites,

infection, and renal failure

Hepatic metastasis is less frequent in cirrhotic patients than

For perforated ulcers in the cirrhotic patient, laparo-

non-cirrhotic patients For patients with chronic

scopic suture is the treatment of choice. In the event of

viral hepatitis B, colorectal cancer-related survival is longer

a hemorrhagic ulcer, endoscopic hemostasis should be fol-

than in noncirrhotic patients due to the lower rate of liver

lowed, if necessary, by surgery in order to maximize elective

involvement Reporting experience of the Mayo clinic,

procedures. Direct hemostasis with arterial ligature and

Gervaz et al. observed a lower rate of hepatic

vagotomy should be preferred over vagotomy-antrectomy.

metastasis in cirrhotic patients (10%) and noted that survival

In cirrhotic patients, who have a gastric cancer, surgery is a

in these patients was long enough for hepatic metastases to

very high risk option in the presence of ascites, hypoalbu-

develop. An alteration of the extracellular matrix stim-

minemia, and Child-Pugh stage C. For stage A and B patients,

ulation of the Kupffer cells defective angiogenesis

it would be preferable to propose type D1 dissection and to

and presence of spontaneous portalcaval shunts

avoid dissection of the hepatic pedicle because of the risk

been proposed to explain this lower risk of hepatic metasta-

of type II lymphatic ascites.

sis. Because of the different prognostic course of colorectalcancer, Child-Pugh stage remains the main prognostic factorfor long-term survival of these patients.

Indications for surgery in the cirrhotic patient

Seven percent of patients with cancer of the esophagus

Two main series have reported results of colorectal cancer

also have cirrhosis Overall morbidity after esophageal

in cirrhotic patients: the Mayo clinic series the

surgery in the operated cirrhotic patient is twice that

French Association of Surgery series The Mayo clinic

observed in the noncirrhotic patient: 17 to 21% versus 3

reported 72 operated cirrhotic patients with colorectal can-

to 8% Mortality does not appear to be affected

cer: Child A (43%), Child B (42%), Child C (15%). Mortality was

by the type of operation; the rate of esophagogastric fis-

13% and morbidity 46%. Fistulae developed in 3%. Cirrhosis-

tulization ranges from 9 to 11% Morbidity, especially

related complications were mainly secondary to liver failure

lung disease, is significantly increased by cirrhosis

and included infection and digestive bleeding. Factors pre-

Mortality is correlated with preoperative liver failure, pro-

dictive of postoperative death were elevated serum bilirubin

thrombin < 60%, presence of ascites and hypoalbuminemia

and low prothrombin level. Ten percent of the patients

The risk of postoperative liver failure is higher in

developed liver metastases. Overall 1, 2 and 3-year survivals

the event of acute alcoholic hepatitis; it is recommended

were 69, 49 and 35%. Survival was better in Child A patients

to wait until transaminase levels return to normal before

than Child B or C patients. Multivariate analysis identified

attempting surgery. For most teams, the presence of Child B

serum albumin and prothormbin level as affecting survival.

or C cirrhosis proscribes surgery The series of 53 patients

Conversely, Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) staging had no

undergoing esophageal surgery reported by the French Asso-

impact on survival, suggesting that the prognosis in these

ciation of Surgery included 46 patients who had elective

patients depends mainly on liver function.

resections followed by esophagogastric anastomosis; 26% of

In the French Association of Surgery series, 54 cirrhotic

the patients had ascites and 81% received a blood transfu-

patients underwent colorectal surgery: 11 for divertic-

sion. Complications developed in 72% of patients:

ular disease and 19 for other diseases. An emergencyprocedure was necessary for 17 patients for peritonitis

• ascites (39%);

(n = 10), obstruction (n = 5), hemorrhage (n = 2). Among the

• pneumopathy (30%);

56 patients who had a resection-anastomosis, 7% developed

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009), doi:

ARTICLE IN PRESS

R. Douard et al.

a fistula. Overall morbidity was 51%, mainly ascites and

exceptional. Nonoperative endoscopic or percutaneous radi-

infection. Overall mortality was 23%. Emergency surgery

ological treatments should be preferred.

and presence of intraoperative ascites were predictive of

For Child B patients, a precise assessment of the liver fail-

operative death. It should be remembered, however, that

ure and the operative risks as a function of the projected

in the cirrhotic patient a protective stomy has specific

operation is required to adapt management practices. The

complications including ascites leakage, ascites infection,

operative risk may be reduced by improving liver function,

stomial disinsertion, peristomial hernia, peristomial eviscer-

reducing the ascites, improving the nutritional status and

ation and peristomial varices

normalizing elevated transaminase levels; surgery may have

Colorectal surgery in the cirrhotic patient is associated

to be delayed but not proscribed. The presence of por-

with higher morbidity and mortality than in the noncirrhotic

tal hypertension with esophageal varices ≥ grade 2 warrants

patient. Factors predictive of operative mortality are those

primary prophylaxis with betablockers. If the postopera-

of surgery in the cirrhotic patient: emergency procedure,

tive risk of hemorrhage is considered high, or if there

serum albumin < 30 g/L, presence of ascites, low prothrom-

is a contraindication for betablockers, prophylactic elas-

bin These factors are included in Child-Pugh staging

tic ligation of the esophageal varices may be proposed.

allowing the distinction of two categories of patients: Child A

Persistence of refractory ascites or severe portal hyperten-

patients who can undergo elective surgery with an expected

sion (history of digestive bleeding by rupture of esophageal

postoperative period comparable to noncirrhotic patients

varices and ≥ grade 2 varices) despite well-conducted medi-

and Child C patients with a high operative mortality (40—50

cal treatment may require preoperative TIPS, which, in this

%) for which surgery should be undertaken only exception-

indication, should replace the peritoneojugular shunt

ally. For Child B patients, the degree of liver failure must

In emergency situations, it is best, whenever possi-

be assessed carefully; correction of an ascites, with TIPS if

ble, to defer surgery of the cirrhotic patient, preferring

necessary, may delay surgery.

a semi-elective intervention. Intensive care and nonoper-ative treatments would be more advisable in these high-riskpatients.

Regarding surgical technique for open procedures,

oblique or transversal approaches are preferable. A multiple

In the cirrhotic patient, extrahepatic surgery is associ-

plane closure of the abdominal wall using slow absorption

ated with higher morbidity and mortality. In the series

thread and overcast stitches is advisable to reduce the risk of

of the French Association of Surgery which collected data

ascites leakage, evisceration, incisional hernia and drainage

on 760 patients, including a very large majority of Child A

should, whenever possible, be avoided. If necessary, non-

patients, overall mortality was 14%. Factors predictive of

traumatic minimal aspiration drainage can be used. Despite

operative mortality were emergency procedure, operation

the lack of solid evidence, it is probably useful to pre-

involving the digestive tract (esophagus, stomach, colon),

pare the colon to reduce the risk of bacterial contamination

serum albumin < 30 g/L, transaminase level more than three

for esophageal, gastric or colorectal surgery. Rigorous sur-

times above the upper limit of normal, presence of ascites

gical technique with special attention to hemostasis and

and intraoperative blood transfusion

lymphostasis is necessary; for cancer surgery, where the

Can the operative risk be reduced for the cirrhotic

prognosis is probably more related to the cirrhosis than the

patient undergoing digestive surgery?

cancer, there is evidence in the literature arguing against

It is important to carefully search for cirrhosis before

extensive nodal dissection.

undertaking abdominal surgery. The problematic is sim-

Hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic agents should be avoided

ple when the cirrhosis is known, for carriers of hepatitis

for anesthesia and perioperative intensive care; it is

C virus, or when chronic alcohol abuse is obvious. For

approximately 20% of patients, however, cirrhosis may go

tors (prothrombin level < 50%, fibrinogen < 1 g/L), schedule

unrecognized and be discovered intraoperatively. Focus

platelet transfusion when the platelet count is less than

should be placed on asymptomatic patients whose imag-

50,000/mm3, and maintain intra- and postoperative sys-

ing work-up displays splenomegaly, hepatic dysmorphism or

temic, renal and hepatic hemodynamics, even at the cost

spontaneous portosystemic shunts as well as patients with

of aggravating postoperative ascites if necessary. Intensive

an isolated thrombopenia, sometimes the inaugural sign of

care must focus on nutritional status and identification and

well-compensated cirrhosis A FibroScan can be useful

rapid treatment of infections, crucial challenges for the

before surgery; its contribution should be assessed

postoperative outcome of the cirrhotic patient.

Three factors known to aggravate the operative risk

should be identified: ascites, serum albumin < 30 g/L,transaminase elevation. For Child A patients, the operative

Conflict of interests

risk of elective surgery is acceptable and surgical indicationsneed not be changed from those proposed for non-cirrhotic

patients, if management is carefully adapted. The laparo-scopic approach should be preferred because it reduces therisk of bleeding, respiratory disorders, infection and abdom-

inal wall defects as well as the prevalence of postoperativeascites.

[1] Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams

For Child C patients, however, operative mortality

R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal

is often 40%; indications for surgery should remain

varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646—9.

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009),

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Digestive surgery and cirrhosis

[2] Northup PG, Wanacker RC, Lee VD, Adams RB, Berg CL. Model

[21] Zwaveling JH, Maring JK, Klompmaker IJ, Haagsma EB, Bot-

for end-stage liver disease (MELD) predicts non-transplant sur-

tema JT, Laseur M, et al. Selective decontamination of the

gical mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Ann Surg 2005;242:

digestive tract to prevent postoperative infection: a random-

ized placebo-controlled trial in liver transplant patients. Crit

[3] Ziser A, Plevac DJ, Wiesner RH, Rakela J, Offord KP, Brown

Care Med 2002;30:1204—9.

DL. Morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients undergoing

[22] Mimoz O, Incagnoli P, Josse C, Gillon MC, Kuhlman L, Mirand A,

anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology 1999;90:42—53.

et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of nefopam vs propacetamol

[4] Belghiti J. Chirurgie œsophagienne chez le cirrhotique. In:

following hepatic resection. Anaesthesia 2001;56:520—5.

Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors. La chirurgie digestive chez le cir-

[23] Williams RL. Drug administration in hepatic disease. N Engl J

rhotique. Paris: Monographies de l'AFC; 1993, p. 61—72.

[5] Blei AT, Mazhar S, Davidson CJ, Flamm SL, Abecassis M,

[24] Lentschener C, Ozier Y. What anaesthetists need to know

Gheorghiade M. Hemodynamic evaluation before liver trans-

about viral hepatitis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003;47:794—

plantation: insights into the portal hypertensive syndrome. J

Clin Gastroenterol 2007;41(Suppl. 3):S323—9.

[25] Valla DC. Complications postopératoires chez les malades

[6] Arroyo V, Jimenez W. Complications of cirrhosis. Renal and

atteints de cirrhose. In: Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors. La

circulatory dysfunction. Lights and shadows in an important

chirurgie digestive chez le cirrhotique. Paris: Monographies de

clinical problem. J Hepatol 2000;32:157—70.

l'AFC; 1993, p. 41—52.

[7] Myers RP, Cerini R, Sayegh R, Moreau R, Degott C, Lebrec D,

[26] Arroyo V, Bernardi M, Epstein M, Henriksen JH, Schrier RW,

et al. Cardiac hepatopathy: clinical, hemodynamic and his-

Rodes J. Pathophysiology of ascites and functional renal failure

tologic characteristics and correlations. Hepatology 2003;37:

in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1988;6:239—57.

[27] Guidelines for the management of complications in patients

[8] Swanson KL, Wiesner RH, Krowka MJ. Natural history of

with cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2008; 32:887—97.

hepatopulmonary syndrome: impact of liver transplantation.

[28] Zarski JP, Bichard P, Bourbon P, Tournery A, Demongeot

J, Rachail M. La chirurgie digestive extrahépatique chez

[9] Mimoz O, Soreda S, Padoin C, Tod M, Petitjean O, Benhamou

le cirrhotique : mortalité, morbidité, facteurs pronostiques

D. Ceftriaxone pharmacokinetics during iatrogenic hydrox-

préopératoires. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1988;12:43—7.

yethyl starch-induced hypoalbuminemia: a model to explore

[29] Belghiti J. La chirurgie digestive chez le cirrhotique : résultats

the effects of decreased protein binding capacity on highly

globaux. In: Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors. La chirurgie diges-

bound drugs. Anesthesiology 2000;93:735—43.

tive chez le cirrhotique. Paris: Monographies de l'AFC; 1993,

[10] Brown MW, Burk RF. Development of intractable ascites follow-

ing upper abdominal surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Am J

[30] Silvain C, Besson I, Ingrand P, Mannant PR, Fort E, Beauchant

M. Prognosis and long-term recurrence of spontaeous bacterial

[11] Sultan S, Pauwels A, Poupon R, Levy VG. Ascite chyleuse du

peritonitis in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1993;19:188—9.

cirrhotique. Étude rétrospective de 20 cas. Gastroenterol Clin

[31] Jouët P, Grange JD. Flore bactérienne et cirrhose. Gastroen-

terol Clin Biol 2003;27:738—48.

[12] Northup PG, Sundaram V, Fallon MB, Reddy KR, Balogun RA,

[32] Martin LF, Booth FV, Reines HD, Deysach LG, Kochman RL,

Sanyal AJ, et al. Hypercoagulation and thrombophilia in liver

Erhardt LJ, et al. Stress ulcers and organ failure in intubated

disease. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:2—9.

patients in surgical intensive care units. Ann Surg 1992;215:

[13] Buyse S, Durand F, Joly F. Évaluation de l'état nutrition-

nel au cours de la cirrhose. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2008;32:

[33] Daley RJ, Rebuck JA, Welage LS, Rogers FB. Prevention of

stress ulceration: current trends in critical care. Crit Care Med

[14] Plank LD, McCall JL, Gane EJ, Rafique M, Gillanders LK, McIlroy

K, et al. Pre- and postoperative immunonutrition in patients

[34] Belghiti J, Cherqui D, Langonnet F, Fekete F. Esophagogastrec-

undergoing liver transplantation: a pilot study of safety and

tomy for carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Hepatogastroenterol-

efficacy. Clin Nutr 2005;24:288—96.

[15] Selberg O, Bottcher J, Tusch G, Pichlmayr R, Henkel E, et

[35] Aranha GV, Greenlee HB. Intraabdominal surgery in patients

al. Identification of high- and low-risk patients before liver

with advanced cirrhosis. Arch Surg 1986;121:275—7.

transplantation: a prospective cohort study of nutritional and

[36] Balzan S, Belghiti J, Farges O, Ogata S, Sauvanet A, Delefosse D,

metabolic parameters in 150 patients. Hepatology 1997;25:

et al. The ‘‘50-50 criteria'' on postoperative day 5: an accurate

predictor of liver failure and death after hepatectomy. Ann

[16] Pessaux P, Msika S, Atalla D, Hay JM, Flamant Y, French Asso-

ciation for Surgical Research. Risk factors for postoperative

[37] Franco D, Charra M, Jeambrun P, Belghiti J, Cortesse A,

infectious complications in noncolorectal abdominal surgery: a

Sossler C, et al. Nutrition and immunity after peritoneovenous

multivariate analysis based on a prospective multicenter study

drainage of intractable ascites in cirrhotic patients. Am J Surg

of 4718 patients. Arch Surg 2003;138:314—24.

[17] Guidelines for the surveillance of patients with uncomplicated

[38] Henrikson EC. Cirrhosis of the liver, with special reference to

cirrhosis and for the primary prevention of complications. Gas-

surgical aspects. Arch Surg 1936;32:413—51.

troenterol Clin Biol 2008; 32:898—905.

[39] Chapman CB, Snell AM, Rowntree LG. Decompensated portal

[18] Fernandez J, Navasa M, Gomez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V,

cirrhosis. JAMA 1931;97:237—44.

et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes

[40] Lemmer JH, Strodel WE, Knol JA, Eckhauser FE. Management

with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatol-

of spontaneous umbilical hernia disruption in the cirrhotic

patient. Ann Surg 1983;198:30—4.

[19] Yeh DC, Wu CC, Ho WM, Cheng SB, Lu IY, Liu TJ, et al. Bac-

[41] Belghiti J, Desgrandchamps F, Farges O, Fékété F. Hernior-

terial translocation after cirrhotic liver resection: a clinical

rhaphy and concomitant peritoneovenous shunting in cirrhotic

investigation of 181 patients. J Surg Res 2003;111:209—14.

patients with umbilical hernia. World J Surg 1990;14:242—6.

[20] Walz JM, Paterson CA, Seligowski JM, Heard SO. Surgical site

[42] Fagan SP, Awad SS, Berger DH. Management of complicated

infection following bowel surgery: a retrospective analysis of

umbilical hernias in patients with end-stage liver disease and

1446 patients. Arch Surg 2006;141:1014—8.

refractory ascites. Surgery 2004;135:679—82.

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009), doi:

ARTICLE IN PRESS

R. Douard et al.

[43] Gillet M. Chirurgie de la paroi chez le cirrhotique. In: Belghiti

[64] Garrison RN, Cryer HM, Howard DA, Polk Jr HC. Clarification of

J, Gillet M, editors. La chirurgie digestive chez le cirrhotique.

risk factors for abdominal operations in patients with hepatic

Paris: Monographies de l'AFC; 1993, p. 53—60.

cirrhosis. Ann Surg 1984;199:648—55.

[44] Leonetti JP, Aranha GV, Wilkinson WA, Stanley M, Greenlee

[65] Lau WY, Leung KL, Kwong KH, Davey IC, Robertson C, Dawson

HB. Umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients. Arch Surg

JJ, et al. A randomized study comparing laparoscopic versus

open repair of perforated peptic ulcer using suture or suture-

[45] Hurst RD, Butler BN, Soybel DI, Wright HK. Management of groin

less technique. Ann Surg 1996;224:131—8.

hernias in patients with ascites. Ann Surg 1992;216:696—700.

[66] Siu WT, Leong HT, Law BKB, Chau CH, Li ACN, Fung KH, et al.

[46] Cobb WS, Heniford BT, Burns JM, Carbonell AM, Matthews BD,

Laparoscopic repair for perforated peptic ulcer: a randomised

Kercher KW. Cirrhosis is not a contraindication to laparoscopic

controlled trial. Ann Surg 2002;235:313—9.

surgery. Surg Endosc 2005;19:418—23.

[67] Takeda J, Hashimoto K, Tanaka T, Koufuji K, Kakegawa T.

[47] Castaing D, Houssin D, Lemoine J, Bismuth H. Surgical manage-

Review of operative indication and prognosis in gastric can-

ment of gallstones in cirrhotic patients. Am J Surg 1983;146:

cer with hepatic cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology 1992;39:

[48] Puggioni A, Wong LL. A metaanalysis of laparoscopic cholecys-

[68] Isozaki H, Okajima K, Ichinona T, Fujii K, Nomura E, Izumi N.

tectomy in patients with cirrhosis. J Am Coll Surg 2003;197:

Surgery for gastric cancer in patients with liver cirrhosis. Surg

[49] Gillet M. Chirurgie des voies biliaires chez le cirrhotique. In:

[69] Lazorthes f, Charlet JP, Buisson T, Ketata M. Chirurgie de

Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors. La chirurgie digestive chez le cir-

l'estomac chez le cirrhotique. In: Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors.

rhotique. Monographies de l'AFC; 1993, p. 91—100.

La chirurgie digestive chez le cirrhotique. Paris: Monographies

[50] Poggio JL, Rowland CM, Gores GJ, Nagorney DM, Donohue JH.

de l'AFC; 1993, p. 73—80.

A comparison of laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy in

[70] Tachibana M, Kotoh T, Kinugasa S, Dhar DK, Shibakita M, Ohno

patients with compensated cirrhosis and symptomatic gall-

S, et al. Esophageal cancer with cirrhosis of the liver: results

stone disease. Surgery 2000;127:405—11.

of esophagectomy in 18 consecutive patients. Ann Surg Oncol

[51] Yeh CN, Chen MF, Jan YY. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in

226 cirrhotic patients: experience of a single center in Taiwan.

[71] Nagawa H, Kobori O, Muto T. Prediction of pulmonary

Surg Endosc 2002;16:1583—7.

complications after transthoracic oesophagectomy. Br J Surg

[52] Fernandes NF, Schwesinger WH, Hilsenbeck SG, Gross GWW, Bay

MK, Sirinek KR, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and cir-

[72] Stahl M, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, Meyer HJ, Waltz MK, Seeber S,

rhosis: a case-control study of outcomes. Liver Transpl 2000;6:

et al. Chemoradiation with and without surgery in patients with

locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J

[53] Schiff J, Misra M, Rendon G, Rothschild J, Schwaitzberg

Clin Oncol 2005;23:2310—7.

S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients. Surg

[73] Gervaz P, Pak-art R, Nivatvongs S, Wolff BG, Larson D, Ringel

S. Colorectal adenocarcinoma in cirrhotic patients. J Am coll

[54] Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Jani K, Shetty AR, Sendhilkumar K,

Senthilnathan P, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cir-

[74] Seymour K, Charnley RM. Evidence that metastasis is less com-

rhotic patients: the role of subtotal cholecystectomy and its

mon in cirrhotic than normal liver: a systematic review of

variants. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:145—51.

post-mortem case-control studies. Br J Surg 1999;86:1237—43.

[55] Bloch RS, Allaben RD, Walt AJ. Cholecystectomy in patients

[75] Song E, Chen J, Ou Q, Su F. Rare occurrence of metastatic col-

with cirrhosis. A surgical challenge. Arch Surg 1985;120:

orectal cancers in livers with replicative hepatitis B infection.

Am J Surg 2001;181:529—33.

[56] Byrne MF, Suhocki P, Mitchell RM, Pappas TN, Stiffle HL, Jowell

[76] Barsky SH, Gopalakrishna R. High metalloproteinase inhibitor

PS, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in patients with acute

content of human cirrhosis and its possible conference of

cholecystitis: experience of 45 patients at a US refrral center.

metastasis resistance. J Natl Cancer Inst 1988;80:102—8.

J Am Coll Surg 2003;197:206—11.

[77] Song E, Chen J, Ouyang N, Wang M, Exton MS, Heemann

[57] Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Kuroda A, Muto T. Treatment of choledo-

U. Kupffer cells of cirrhotic rat livers sensitize colon can-

cholithiasis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Surgical treatment

cer cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Br J Cancer 2001;84:

or endoscopic sphincterotomy? Ann Surg 1993;218:68—73.

[58] Chijiiwa K, Kosaki N, Niato T, Kameoka N, Tanaka M. Treat-

[78] Gervaz P, Scholl B, Mainguene C, Poitry S, Gillet M, Wexner S.

ment of choice for choledocholithiasis in patients with acute

Angiogenesis of liver metastasis: role of sinusoidal endothelial

obstructive suppurative cholangitis and liver cirrhosis. Am J

cells. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:980—6.

[79] Utsunomiya T, Matsumata T. Metastatic carcinoma in the cir-

[59] Prat F, Tennebaum R, Pnsot P, Altman C, Pelletier G, Fritsch J,

rhotic liver. Am J Surg 1993;166:776.

et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with liver cirrho-

[80] Wind P, Teixeira A, Parc R. Chirurgie colo-rectale chez le

sis. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;43:127—31.

cirrhotique. In: Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors. La chirurgie diges-

[60] Park Do H, Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee SS, Choi JS, Song MH, et

tive chez le cirrhotique. Paris: Monographies de l'AFC; 1993,

al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy vs endoscopic papillary balloon

diloation for cholodecholithiasis in patients with liver cirrhosis

[81] Conte JV, Arcomano TA, Naficy MA, Holt RW. Treatment of

and coagulopathy. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:180—5.

bleeding stomal varices. Report of a case and review of the

[61] Mariette D, Belghiti J. Chirurgie du pancréas et cirrhose. In:

literature. Dis Colon Rectum 1990;33:308—14.

Belghiti J, Gillet M, editors. La chirurgie digestive chez le cir-

[82] Conférence de consensus : complications de l'hypertension

rhotique. Monographies de l'AFC; 1993, p. 105—12.

portale chez l'adulte. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004;28:

[62] Rabinovitz M, Schade RR, Dindzans V, Van Thiel DH, Gavaler

JS. Prevalence of duodenal ulcer in cirrhotic males referred

[83] Azoulay D, Buabse F, Damiano I, Smail A, Ichai P, Dannaoui

for liver transplantation. Does the etiology of cirrhosis make a

M, et al. Neoadjuvant transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

difference? Dig Dis Sci 1990;35:321—6.

shunt: a solution for extrahepatic abdominal operation in cir-

[63] Lehnert T, Herfarth C. Peptic ulcer surgery in patients with liver

rhotic patients with severe portal hypertension. J Am Coll Surg

cirrhosis. Ann Surg 1993;217:338—46.

Please cite this article in press as: Douard R, et al. Operative risks of digestive surgery in cirrhotic patients. GastroenterolClin Biol (2009),

Source: http://www.espoire.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/chirurgie-du-cirrhotique-GCB-2009.pdf

INTRODUZIONE (Mt. 13,1-3a) Le Parabole del Regno (Mt. 13) I 5 "discorsi" del vangelo di Matteo Le 7 Parabole del Regno Discorso della montagna (Mt. 5-7) Parabola del seminatore Discorso Missionario (Mt. 10) Parabola della zizzania Discorso delle parabole (Mt. 13) Parabola del chicco di senape

Top 10 Tips for Defending Mass Torts in New Jersey by James J. Ferrelli and Alyson B. Walker New Jersey is home to many mass torts—asbestos, hormone replacementtherapy (HRT), NuvaRing, Vioxx, Fosamax, Accutane, and Bextra/Celebrex—toname just a few. With plaintiffs filing numerous cases in the Garden State, it'seasy to fall into the mindset that New Jersey is for plaintiffs. But don't get caughtin that trap and become complacent, filing rote motions and litigating onautopilot. With the right strategy and tactics, New Jersey can be for defendantstoo. Here are our top 10 tips for defending mass torts in New Jersey: