Project report - riparian planting and management guidelines for tangata whenua

STATE OF THE TAKIWĀ

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai

Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-

Heathcote Estuary and its Catchment

Craig Pauling, Te Marino Lenihan, Makarini Rupene,

Nukuroa Tirikatene-Nash & Rewi Couch

Toru / July 2007

mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei

for us and our children after us

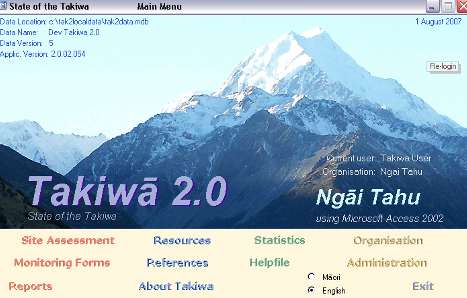

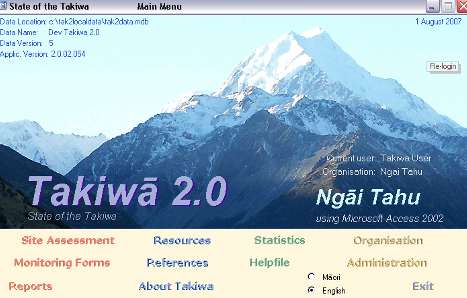

This report was produced using Takiwā 2.0 – a database developed by

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Environmental Science & Research, and

supported by the Ministry for the Environment

Cover Photographs:

Centre: View over Te Ihutai from the Sewage Outfal (Photograph: C. Pauling, 2007)

Bottom (Left to Right): Wairārapa Stream (Avon River) at the end of Wai-iti Terrace (Photograph: C. Pauling,

2007); Electric Fishing on the Heathcote River at Annex Road (Photograph: J.Bond, 2007); and The Ōpāwaho /

Lower Heathcote River at Garlands Road Bridge (Photograph: C. Pauling, 2007).

Whakarāpopotanga / Executive Summary

This report outlines the results of a cultural environmental health assessment of Te Ihutai/the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and its catchment undertaken by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, in-conjunction with members of Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Ngāti Wheke, between March and May 2007. This study was carried out for Environment Canterbury as part of a wider research project being led by the Avon-Heathcote Estuary Ihutai Trust called „Healthy Estuary & Rivers of the City‟.

The purpose of the study was to undertake a review of the cultural health of the Ihutai catchment, including the Ōtākaro (Avon) and Ōpāwaho (Heathcote) rivers, through data col ected at 30 river, estuary and coastal sites using the Takiwā cultural environmental monitoring and reporting tool.

Takiwā is an environmental monitoring system developed by Ngāi Tahu that is aimed at facilitating Tāngata Whenua to gather, store, analyse and report on information in relation to the cultural health of significant sites, natural resources and the environment within their respective takiwā (tribal areas). The approach uses a series of assessment forms to enable the quantification of cultural health scores based on a number of factors including suitability for harvesting mahinga kai, physical and legal access, site pressures, degree of modification and the identification of valued as well as pest species present. Other tools including the Cultural Health Index (CHI), Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit (SHMAK), E.coli testing and electric fishing surveys are also used to complement the Takiwā assessments.

Overall, the monitoring results and subsequent analysis found the catchment to be in a state of poor to very poor cultural health. Most significantly only 3 sites, Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Te Karoro Karoro (South Brighton Spit) and Tuawera (Cave Rock/Sumner Beach) were considered good enough to return to.

Site and water quality in the Avon catchment was found to be healthier than in the Heathcote catchment. However, native species abundance was found to be greater in the Heathcote catchment, and poorest at estuary and coastal sites. In particular, the impacts of historical and ongoing drainage and untreated stormwater, the loss of native vegetation, including wetlands, grasslands and lowland forests, and the decline of water quantity within the catchment were identified as major issues influencing the assessment. Of most concern, however, were the e.coli and anti-biotic resistance results which show widespread contamination from both human and agricultural sources in the catchment.

Although the catchment received a poor assessment, a number of sites and features were seen as positive, and provide ideas for how future management may be able to improve the cultural health of the Ihutai catchment. These include the presence and abundance of remnant and/or restored native vegetation at sites such as Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Waikākāriki (Horseshoe Lake), Ōruapaeroa (Travis Wetland), the Wigram Basin and Westmorland, as well as the occurrence of freshwater springs at Jellie Park and Templetons Rd.

Protecting, enhancing and extending such areas and features and investigating and eliminating sources of contaminants wil be the most important challenges for the future management of the Ihutai catchment. Ongoing monitoring, including cultural assessments wil be vital in understanding the success, or otherwise, of any such actions.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary i

Rārangi Ūpoko / Contents

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary ii

1 Te Whakatuwheratanga / Introduction

Te Ihutai/the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and its tributaries, the Ōtākaro/Avon and Ōpāwaho/Heathcote Rivers are iconic cultural, recreational and ecological features of Christchurch City and the wider Canterbury area. Yet, as a consequence of the development of both the city and the community it supports, the estuary and its catchment have undergone dramatic change and degradation, particularly in relation to indigenous flora and fauna, and water quality.

For Tangata Whenua, these impacts have had a direct and significant impact on the customary relationship with the Ihutai catchment, and resulted in the estuary and its catchment being of little, if any, value as a mahinga kai (customary food/source).

While some of the issues facing the Ihutai catchment have been documented, very little is known about the extent of change that has taken place for, or how the current health of the catchment is viewed by, Tangata Whenua. This report therefore outlines the results of a cultural environmental health assessment study that marks the first attempt to quantify these issues from a Tangata Whenua perspective.

The assessment was undertaken by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, in-conjunction with members of Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Ngāti Wheke, between March and May 2007, as part of a wider water monitoring programme being facilitated by the Avon-Heathcote Estuary Ihutai Trust and supported by the Christchurch City Council, Environment Canterbury and the Ministry for the Environment.

The study col ected data from 30 sites within the Ihutai catchment using the Takiwā cultural environmental monitoring and reporting tool. This included the use of the Takiwā site assessment, Cultural Health Index and Stream Health Assessment and Monitoring tools, E.coli and anti-biotic resistance testing as wel as electric fishing surveys. The field-collected site data was subsequently loaded into the Takiwā database to enable a catchment analysis to be undertaken.

Specifical y, the report is structured in the fol owing way:

Section 1 introduces the report with a brief background to the study,

including major drivers, aims and objectives.

Section 2 gives an overview of the State of the Takiwā Database and

Monitoring tool used within the study and to produce this report.

Section 3 gives an overview of the process and methods of data col ection,

including those of Takiwā and the other tools used during the study.

Section 4 gives the results of the study, including the literature review of

traditional health and associations, site assessment data and a discussion of the current cultural health of the Ihutai catchment.

Final y, Section 5 concludes the report with a summary of major points and

recommendations of the study.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 1

1.1 Tāhuhu Kōrero / Background Te Ihutai and its catchment are of immense cultural and historical importance to Tangata Whenua, being a place of significant settlement and food gathering by Waitaha, Ngāti Mamoe and Ngāi Tahu for over 600 years. Sites along both the Avon and Heathcote Rivers, in and around the estuary, and on the coastline near the mouth of the estuary were known and used due to the availability and abundance of mahinga kai resources. Freshwater fish and shel fish, as well as numerous native plant resources, waterfowl and forest birds could be gathered from the network of springs, waterways, swamps, grasslands and lowland podocarp forests that made up the estuary catchment, much of which was stil present at the time of European settlement (Tau, Goodall, Palmer & Tau 1990; Christchurch City Libraries 2006; Christchurch City Council 2007).

The modern settlement and development of the city of Christchurch has, however, had a dramatic impact on the health of the entire catchment, and inturn the values Tangata Whenua have for the area. Drainage of the original swamplands has lead to extreme sedimentation within both the Avon and Heathcote Rivers and the estuary itself. Industrial and residential development has seen the destruction of extensive areas of native vegetation, the degradation of water quality and the local extinction and/or degradation of native fish and bird species, as well as the depositing of pol ution and toxins within the catchment. The taking of the Te Ihutai Māori Reserve in 1956 under the Public Works Act as part of the Christchurch sewage works development and the subsequent discharge of human effluent into the estuary have compounded these, and created further problems (Bolton-Ritchie, Hayward & Bond 2006; Tau et al 1990).

Recently however, and in response to this, the Avon-Heathcote Estuary Ihutai Trust embarked on an ambitious and important journey to improve the health of the estuary and its catchment, releasing the Ihutai Management Plan in 2004 (Avon-Heathcote Ihutai Trust 2004). Following this, the Trust developed a comprehensive water quality monitoring programme entitled „Healthy Estuary and Rivers of the City‟ (Bolton-Ritchie et al 2006) aimed at identifying long term environmental changes, assessing current water quality, and developing a baseline of information that may assist in measuring the success of, and inform, the restoration and future management of Te Ihutai.

To carry out this programme, the Trust identified the need to involve Tangata Whenua and gather water quality data that would be able to take into account historical and cultural values associated with Te Ihutai, including mahinga kai. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu were engaged by the Trust to facilitate this element of the programme through the use of its Takiwā cultural environmental monitoring and reporting tool.

1.2 How did this study come about? After hearing about the pilot State of the Takiwā study completed by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu for the Waiau River in Southland (Pauling, Mattingley & Aitken 2005), and a subsequent study within the Wairewa/Lake Forsyth Catchment (Pauling, Cranwell & Ataria 2006), Jenny Bond of Environment Canterbury contacted Craig Pauling at Te Rūnanga in early 2006 to discuss the possibility of undertaking cultural monitoring as part of the monitoring programme planned for the estuary by the Avon-Heathcote Ihutai Trust.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 2

After several further conversations and a successful funding application by the Trust, Jenny contacted Craig again in mid 2006 to confirm if Te Rūnanga could be part of the project to provide training and coordination of cultural monitoring for Te Ihutai. In the meantime, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu had been successful with their own funding application to further develop the Takiwā cultural environmental monitoring and reporting tool.

Te Rūnanga then organised and ran a workshop at Wairewa Marae, Little River in late October 2006 with local Papatipu Rūnanga in relation to Takiwā and future fieldwork involving the tool. Environment Canterbury participated in the workshop and Jenny Bond outlined the Ihutai project, along with other monitoring related initiatives to rūnanga participants. Te Marino Lenihan of Ngāi Tūāhuriri expressed an interest in the Ihutai project and a further meeting was planned to discuss Ngāi Tahu involvement.

In March 2007, Craig Pauling met with Te Marino Lenihan, Makairini Rupene and Jenny Bond to further develop the project and began to develop aims and objectives for the study as well as identifying potential monitoring sites within the Ihutai catchment. Craig Pauling also informed Rewi Couch of Ngāti Wheke about the study and invited him to be involved in the fieldwork.

From the meeting and conversations a plan and budget was developed for the study, with monitoring work commencing in mid-March 2007. A full copy of this plan is included as Appendix A to this report. The aims and objectives of the study, summarised from the plan, are outlined below.

1.3 Ngā Whāinga / Study Aims and Objectives The major objective of the study was to:

Undertake a review of the cultural health of the Ihutai catchment, including

the Ōtākaro (Avon) and Ōpāwaho (Heathcote) rivers, through the gathering, analysis and reporting of data col ected using the Takiwā cultural

environmental monitoring and reporting tool.

This objective was supported by the following aims, to:

Identify monitoring sites and targets in the Ihutai catchment, important

resources such as people and equipment needed and develop a plan for the gathering of data in conjunction with rūnanga monitoring team members (March 2007).

Provide training to rūnanga monitoring team members in the use of the

Takiwā tool and other environmental monitoring processes (March 2007).

Undertake the gathering of data for the Ihutai catchment, using Takiwā,

CHI, SHMAK and E.coli assessments at selected sites from the source to the sea (Ki Uta Ki Tai) and input the col ected data into Takiwā 2.0 (by May 2007).

Analyse the col ected data and complete a cultural health baseline report

for the Ihutai catchment to assist future management and planning and to contribute to the „Healthy Estuary and Rivers of the City‟ monitoring programme (by June 2007).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 3

2 Te Puna / Takiwā Monitoring Tool

The Takiwā Monitoring tool used within this study is an important factor in the development of this report. To fully appreciate and understand the data presented in this report, it is therefore important to outline how the Takiwā database and monitoring forms are structured and used. The following sub-sections therefore give an overview of the key features of the database and monitoring forms and how these helped to create this report.

2.1 What is State of the Takiwā? State of the Takiwā is an environmental monitoring approach developed by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu as part of their Ki Uta Ki Tai - Mountains to the Sea Natural Resource Management framework (Pauling 2004) and outlined in the tribal vision, Ngāi Tahu 2025 (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu 2003). Its development has been partly funded by the Ministry for the Environment and supported by Environmental Science and Research, Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, NIWA, Envirolink Southern Community Laboratories, Environment Southland and Environment Canterbury.

In simple terms, State of the Takiwā describes a cultural values based environmental monitoring and reporting system that is aimed at facilitating Tāngata Whenua to gather information, assess and report on the cultural health of significant sites, natural resources and the environment within their respective takiwā, that wil in turn assist them in managing the environment into the future.

State of the Takiwā is a play on words from the conventional, largely western science based State of the Environment approach, but that takes into account Māori cultural values, such as mauri and mahinga kai, and that aims to complement standard scientific measures of environmental health.

Ngāi Tahu 2025 defines State of the Takiwā as "[a]n environmental monitoring and reporting approach that integrates Mātauranga Māori and Western Science to gather information about the environment and to establish a baseline for the creation of policy and improvement of environmental health. A programme developed as an alternative to conventional state of the environment reporting used by the Ministry for the Environment that takes into account Tāngata Whenua values" (TRoNT 2003, p47-48).

The major objective behind State of the Takiwā is to ensure that Tāngata Whenua can build robust and defensible information on the health of the environment, which can in turn be used to assess the effectiveness of both internal policy and practices as wel as those of external agencies, including local councils who have statutory responsibilities to undertake monitoring and report on the state of the environment (Pauling 2003).

Central to the approach is the gathering of information on the health of the environment using specially developed data-forms and the collation of this information into a specifical y designed database from which analysis is possible and reports can be prepared. An overview of the Takiwā forms and database is included below.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 4

2.2 The Takiwā Database Takiwā is a special y developed Microsoft Access 2002 runtime application linked to a physical y separated database, which can be run on any PC by downloading it from an instal ation CD-ROM. The database is password protected, and al data entries are automatical y stamped with the initials of who created it and when, and who last modified it. The database also has facilities for creating dated backup copies of the data tables, which can be stored remotely to ensure the safety of the data. It also includes an easy to use Helpfile and has a bi-lingual interface that can display key headings in either Te Reo Māori or English, depending on the current user‟s preference.

The primary aim of the Takiwā database is to facilitate data col ection and make information available to Tāngata Whenua, to help them identify and quantify the current or changing quality of a particular site, and to be able to report this data in an easy, clear and repeatable way. This is achieved by the inclusion of a site assessment module for storing, analysing and reporting data collected on particular sites, and a print centre where monitoring forms for data collection and standard reports can be produced.

Site Assessment Module

The Site Assessment module identifies environmental monitoring sites and records details from both present-day visits by participants as well as historical information. Data gathered is in a combination of reasoned multi-choice evaluation of criteria (eg. access for harvesting: 1 = very poor -- 5 = very good), and ad-hoc comments of visitor impressions (see Figure 1 below). Within this module, details based on Takiwā Monitoring, Cultural Health Index and SHMAK forms can be entered to describe a geographically-defined site and the details of the visit as wel as being able to assess environmental and other qualities in a consistent fashion over time.

Figure 1. Takiwā Site Assessment Module

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 5

The structure of the database ensures that, in the future, the data can be interrogated to answer such questions as:

Has quality improved or deteriorated over the years?

How many sites of interest exist in different areas?

How much information is available on that area?

Who has visited it (for assessment) and when?

Have native birds, plants, etc improved or deteriorated over the years?

At which sites have people seen kererū, totara, or other listed taonga?

How have their presence changed over the years?

The Site Assessment module also includes a section label ed „journal‟ where important historical information and references about a particular site can be stored. A further feature is the image portal where an unlimited number of photographs or other diagrams (.jpg, .gif or .bmp format) can be associated with the site.

In order to grade and compare sites and visits, index calculations have been included within the database. These include an overal site health assessment index, a species abundance index, and the Cultural Health Index for waterways (Tipa & Tierney 2003 & 2006). The Site Assessment module also includes a module to enter data from the Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit (Biggs, Kilroy & Mulcock 2000) and to produce scores for stream habitat quality, and invertebrate and periphyton health. Al indexes can be recalculated for either the current questionnaire, or for al questionnaires in the database (Mattingley 2005).

Takiwā Monitoring Forms

Takiwā includes a series of special y developed monitoring forms which can be printed directly from the database, used to gather information about sites and facilitate the storage and reporting of data from the field. These include the Takiwā Site Definition, Visit and Assessment forms. Takiwā also currently includes forms for the Cultural Health Index and Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit.

The aim of the Takiwā monitoring forms are to record observations and assessments by tāngata whenua for a particular site and at a particular time relating to key cultural values and indicators of environmental health, such as mahinga kai. The forms were developed through discussion with both tāngata whenua groups and monitoring experts and by reviewing previously developed monitoring tools.

Feedback dictated that the monitoring forms needed to be simple, rather than being overly complicated or abstract and that the forms should attempt to capture the cultural information and values about a site, which is normally internalised during mahinga kai (food gathering) or similar activities and often cal ed „anecdotal information‟.

The overal goal of the data col ection and storage achieved by the form and database was to make this important information more defendable, accessible, useable and quantitative.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 6

Forms and indicators from other monitoring toolkits were investigated and used to identify relevant formatting as well as the type of questions that could be used to capture appropriate information in relation to cultural values and indicators. These included:

Kaimoana Monitoring Guidelines (Otaraua Hapū 2003);

Cultural Steam Health Index (Tipa & Tierney 2003);

Iwi-Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit (Ogilvie & Penter 2001);

Māori Indicators Wetland Monitoring Tool (Harmsworth 2002);

Forest Monitoring and Assessment Kit Site Assessment Kit (Handford &

Associates Ltd 2003);

NIWA Freshwater Fish Database Form (NIWA 2003).

From this analysis and discussion with Tāngata Whenua and other experts, the following indicators were identified as being most important to include in the main Takiwā monitoring form:

Heritage/Site Significance;

Amount of pressure on the site from external factors;

Levels of modification/change at a site;

Suitably of the site for harvesting mahinga kai;

Access issues in relation to the site;

Overal health/state of a site;

Presence, abundance and diversity counts for native bird, plant and fish

species, other cultural y significant resources as wel as exotic (including pest and weed) species; and

Wil ingness to return to the site.

Other details that were seen as being important to record were in relation to general visit and site details (date, time, weather conditions, site location, legal protection etc). This was achieved by the development of two separate but interdependent forms – The Site Definition and Visit Details Form. The visit details form also includes prompts to ensure photographic references are recorded for a site.

Examples of al the forms included in Takiwā and used in this study are shown in Appendix B.

Takiwā Reporting Functions

The final critical feature of the Takiwā database is the printable query and reporting function. This function allows users to print a range of reports by simply selecting the type of report (from a range of options) and pushing a print button within the database. These reports can also be exported to Word or Excel to assist in report writing or graphic representations of the data.

This is made possible through a „Print Centre‟ that offers a range of different reports for sites, visits and questionnaires. The print centre is accessed through buttons on both the Takiwā Main screen and on the Site Evaluation screen. When a user in is the print centre, it already knows which Site, Visit and Questionnaire were last used on the Site Evaluation screen, and these are listed, with the last one viewed being already selected.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 7

3 Ngā Kauneke / Methods

The data col ection undertaken within this study was conducted over 6 days between the 16th of March and the 11th of May 2007, at 30 sites situated along the Avon and Heathcote rivers, around the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and along the Canterbury Coast at New Brighton and Sumner.

The monitoring team consisted of members from Ngāi Tūāhuriri, Ngāti Wheke and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and were supported by Environment Canterbury, the Avon-Heathcote Ihutai Trust and Envirolink Southern Community Laboratories.

The data col ection primarily involved cultural health site assessments using the Takiwā tool. This was further complemented by the use of the Cultural Health Index, Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit and electric fishing surveys at all river sites, and the collection and testing of water samples from all sites for the analysis of E.coli and antibiotic resistant E.coli.

The following sub-sections give an outline of the people involved, equipment used, sites assessed, and methods used to collect data at each site, as well as an overview of the background research and data analysis undertaken.

3.1 Tāngata Arotake / Monitoring Team The following people were involved in the study and fieldwork:

Te Marino Lenihan (Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Makarini Rupene (Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Nukuroa Tirikatene-Nash (Ngāi Tūāhuriri)

Rewi Couch (Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke)

Craig Pauling (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu)

3.2 Taputapu Arotake / Monitoring Equipment The following equipment was used during the study and fieldwork:

Vehicles (Private) Takiwā forms, CHI forms, SHMAK Kit, manual and forms Electric Fishing Machine, Probe and Nets Waders and Protective Jacket/Gear E.coli kit (Vials, Chil y pads, Chil y Bin, Forms) Digital Camera, GPS unit and Binoculars Maps and Monitoring Plan Pens, folders and identification booklets First Aid Kit Tea and Coffee Laptop and Takiwā software (for the storage and analysis of data)

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 8

3.3 Wāhi Arotake / Monitoring Sites Monitoring sites were chosen from the entire Ihutai catchment to gain a good mix of traditionally significant sites, land use issues, historical changes, as well as sites of contemporary significance. Some sites were also chosen to correspond with sites being used for other water quality monitoring in the wider programme, while other sites were simply chosen due to access issues.

Al sites were purposely selected to represent a „Ki Uta Ki Tai‟ or source to sea philosophy, being situated along the Avon and Heathcote rivers, around the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and along the Coast at New Brighton and Sumner. This included identifying sites within the source tributaries, drains and springs of both the Avon and Heathcote rivers, including Dudley Creek, Wairārapa Stream, Ilam Stream, Waimairi Stream, Horseshoe Lake, Travis Wetland (Avon catchment) and Wigram Basin and Cashmere Stream (Heathcote catchment). The sites assessed during the study are listed below along with an indication of the site significance and major surrounding land use issues.

Site Name

Ōtākaro / Avon River

Avonhead @ Russley Rd Western most source of the Avon River and

Waimairi Tributary

Burnside Park / West

Source of West Burn Tributary flowing into

Waimairi and significant recreational area – rugby, soccer and cricket

Source of Dudley Creek, northern most tributary

Wairārapa Stream @

Near source of Hewlings Stream and Wairarapa

Stream, including spring fed lake and significant recreational area within urban park – public pool, skatepark

Waimairi Stream @

Mid-catchment reference (ease of access)

Ilam Stream @ Athol

Source of Ilam Stream tributary

Pūtarikamotu / Ilam

Traditional settlement and food gathering site,

Stream @ Deans Bush

remaining native forest remnant, protected

Waipapa / Little Hagley

Traditional settlement and food gathering site,

upper most main channel site

Ōtautahi / Kilmore St

Traditional settlement and food gathering site

Contemporary recreational site – rowing /waka

ama /hockey and complimentary sample site.

Te Oranga / Horseshoe

Traditional settlement and food gathering site,

significant urban drainage sink and

native/natural wetland/spring remnant

Ōruapaeroa / Travis

Traditional settlement and food gathering site,

significant urban/rural drainage sink and

native/natural wetland remnant

Contemporary recreational area – waka ama,

former public works site and lower most Avon

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 9

Ōpāwaho / Heathcote River

Wilmers Rd/Warren Park

Source of main Heathcote River, upper most

catchment site, between Warren Park

(recreational area) and Wigram Air base

Significant source spring of upper Heathcote

River between rural land, urban development

and significant recreational reserve, and

complimentary sample site.

Significant drainage sink and historic sources of

upper Heathcote river – contemporary

recreational area – rugby league, horse riding,

agricultural show grounds, area also owned by

Ngāi Tahu Property

Te Heru o Kahukura /

Situated between Ngāi Tahu Property subdivision Urban /

development, Linden Grove (former Sunnyside

Hospital) and Spreydon Primary School, and

complimentary sample site.

Waimokihi / Pioneer

Significant recreational area – public pool,

soccer and cricket as well as site of Kura

Kaupapa Māori, and complimentary sample site. School

Near source of Cashmere Stream tributary

Beckenham Library

Mid-catchment reference

Ōpāwaho / Garlands

Traditional settlement and food gathering site

Woolston Industrial

Settlers Reserve /

Inter-tidal, lower most Heathcote river site,

adjacent to new Māori tourism development

Te Ihutai / Estuary

Te Kai a Te Karoro /

Traditional settlement & food gathering site and

contemporary recreational site, and

complimentary sample site.

Te Karoro Karoro / South Traditional settlement and food gathering site on Reserve/ Brighton Spit

northern mouth of Estuary

Outfall of Bromley Oxidation Ponds and near

Pleasant Point Yacht Club and opposite Te Kai o

Te Raekura / Redcliffs

Traditional settlement and food gathering site,

beach access and complimentary sample site.

Rapanui / Shag Rock

Traditionally significant site, contemporary

recreational swimming area, and complimentary Beach sample site.

Te Tai o Maha-a-nui / Pegasus Bay

Tuawera /Cave Rock

Traditionally significant site, contemporary

recreational swimming/surfing area, and

complimentary sample site.

Ōruapaeroa / New

Traditionally significant site, contemporary

recreational swimming/surfing area

Commerce / Coastal

The location of these sites are shown on map 1 on the following page.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 10

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 11

3.4 Kauneke Arotake / Data Collection & Assessment

The data col ection undertaken within the study involved the fol owing types of assessment:

1. Takiwā Site Assessments (all sites); 2. E.Coli Water Testing (all sites, except Avonhead & Westburn); 3. Cultural Health Index (CHI) Waterway Assessments (river & stream sites only); 4. Stream Health Monitoring (SHMAK) Assessments (river & stream sites only,

except Avonhead, Westburn and Wigram Basin);

5. Electric Fishing Surveys (freshwater sites only, except Avonhead, Westburn,

Dudley, Royds, Athol, Pūtarikamotu, Waipapa, Ōtautahi & Wigram).

Further details of the methods for the different assessment methods used in the study are outlined in the following sub-sections. The general process followed for the data col ection at all sites involved the following steps:

After arriving at the site, the monitoring team gathered together so that any

appropriate mihi, karakia and/or kōrero could be given.

The team then completed the Site Definition and Visit Details forms,

including obtaining GPS coordinates and photographic records for the site.

The team then completed the Takiwā site assessment form and gathered

the water sample for E.coli testing. At al river/stream sites the team then undertook the various tests as part of the SHMAK kit, completed the Cultural Health Index water quality form, before final y undertaking an electric fishing survey of the site.

Before departing, a general kōrero/discussion was held about the site, and

travel and other details about the next site and/or activity.

Takiwā Site Assessments

The first step of the Takiwā site assessment involved completing the Site Definition form. This required recording information on the site name, referring to both traditional and current names, the location, legal protection issues, and the traditional significance and condition of the site, as well as recording the exact geographical details using a GPS receiver. For Takiwā assessments, a site is defined as the area within 100 metres of the point of monitoring.

In the second step, visit specific details such as the individuals involved, the date, time, weather conditions and other information relevant to the visit, including photographic records are then recorded on the Visit Details form.

The third step involved completing the site assessment form. The first part of the site assessment form involved ranking the fol owing aspects of site health using a 1 to 5 scale, where 1 is the least/worst score and 5 is the highest/best score:

Amount of pressure from external factors; Levels of modification/change at the site; Suitably for harvesting mahinga kai; Access issues; Wil ingness to return to the site (simply a yes or no answer); and Overal state/health of the site.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 12

The second part of the site assessment form involved undertaking abundance and diversity counts for native bird, plant and fish species, other resources (such as stone, bone or driftwood) as well as introduced plant and animal species. This was achieved via visual and aural identification of individual species along with a weighting given to their relative abundance (few/some/many) at the site. The assessment of fish species was undertaken at all river sites through electric fishing (see section 3.4.5 below).

The assessment of taonga plant species also included a question to indicate the relative dominance of native species versus exotic or weed species at the site. This is represented as a percentage of the total site area covered by the taonga plants and gives an important indicator of change at the site over time.

From this information, index scores are quantified for overall site health (total averaged factor scores out of 5) and species abundance (an open ended number, which can be positive or negative and where higher is better). The site health score is then assigned a rank from very good to very poor and used in the overal analysis of the catchment (Pauling 2007).

E.Coli Water Testing

E.coli water testing involved two assessments, using a single 100ml water sample collected from each site:

Laboratory analysis to quantify the total E.coli in the sample (per 100mls).

Further laboratory analysis of the sample to identify the main source of any

E.coli present in the river water, through antibiotic resistance analysis.

Water samples were collected in plastic screw top 100ml vials, labelled with the site code, put on ice in a chil y bin, and delivered to Hill‟s Laboratory for analysis within 24 hours. Results from the laboratory analysis were then sent back to the monitoring team for inclusion in the analysis of the study.

E.coli testing was not completed at the Avonhead and Westburn sites due to there being no water present in the streams at the time of monitoring.

Background to E.coli and Anti-biotic Testing

Faecal Coliforms are a group of bacteria that include E.coli. Members of the coliform group also include other bacteria that may be found in the soils, and also in the intestines of birds. A positive faecal coliform result therefore indicates the possibility of faecal contamination, but is not totally reliable.

The presence of E.coli, however, indicates contamination with faecal material from the intestinal tract of a mammal or birds. As a general rule, the drinking water standard uses the detection of 1 E.coli in 100ml of water as rendering it unfit for human consumption (Ministry of Health 2000). There are also standards for shel -fish gathering and contact recreation (Ministry for the Environment 2003). A summary of these standards are included as Appendix C of this report.

Drinking water supplies susceptible to contamination with sewage or other excreted matter may cause outbreaks of diarrhoea or intestinal infections. Kaimoana gathered near faecal y contaminated water may also contain intestinal pathogens because shel fish filter and concentrate organisms inside their body.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 13

It is sometimes difficult to detect bugs like campylobacter that cause health problems, because they occur in very low numbers. Instead we rely on tests that wil reveal the presence of bugs associated with faeces (such as E.coli and faecal coliforms) that show contamination of the water, but do not usual y cause harm themselves.

A further piece of analysis that can be carried out with E.coli is the detection of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance in E.coli is a strong indication that the E.coli has previously been exposed to antibiotics, or has acquired the antibiotic resistance factor by association with an E.coli containing the factor. Specific antibiotics (eg. Apramycin) are uniquely associated with the agricultural use of antibiotics, and the detection of this resistance indicates agricultural origin of the E.coli. Resistance to other antibiotics used solely by humans can therefore indicate contamination from human effluent and so on. Moreover, a sample showing no resistance or „sensitivity‟ indicates the contamination is from a natural source, such as a bird or from the soil (Pauling et al 2005).

Cultural Health Index Waterway Assessment

The Cultural Health Index (CHI) was developed by Gail Tipa and Laurel Tierney with support from the Ministry for the Environment and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. The original CHI was completed in 2003 (Tipa & Tierney 2003), with a revised version being published in 2006 (Tipa & Tierney 2006).

The methodology for the Cultural Health Index is very similar to the Takiwā site assessment, where a form is completed relating to a number of ranking questions, along with the identification of valued bird, plant and fish species. The major difference is that the Cultural Health Index is focussed solely on assessing the cultural health of the waterway at a particular site, rather than land resources over the entire site. Other obvious differences are the exclusion of assessments for pest and weeds and other resources. Another difference in the CHI is the grading and scoring system associated with it.

The CHI has three components - traditional association, mahinga kai and stream health. To derive the index at a particular stream site, first traditional association is identified, then mahinga kai values are assessed, and final y cultural stream health is evaluated. Almost all the necessary data for these measures are derived from the recording forms.

Component 1 – Site status

This identifies whether or not the site is of traditional significance to Tāngata Whenua and can be determined when the sites are first selected. The second part of the status grade indicates whether Tāngata Whenua would return to the site in future.

Stream sites are classified according to traditional association and intention to use in the future, including:

Is there a traditional association between Tāngata Whenua & the site? Sites

of traditional significance are assigned an 'A'. Sites that do not have a traditional association are assigned a 'B'.

Would Māori come to the site in the future? Whether the Tāngata Whenua

would return to the site or not is also recorded. If the Tāngata Whenua would return, the site is awarded a 1, and if not, a 0.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 14

Component 2 – Mahinga kai

Examining the health of mahinga kai recognises that mauri is tangibly represented by the physical characteristics of a freshwater resource, including the indigenous flora and fauna, the fitness for cultural usage and its productive capacity.

The mahinga kai measure has four elements, each of which is scored on a 1–5 basis (1 is poor health, 5 is very healthy):

1. Identification of mahinga kai species present at the site. A score is given

depending on the number of species present. The productive capacity of a site is reflected in the ability of the freshwater resource to yield mahinga kai.

2. Comparison between the species present today and those sourced

traditional y from the site. A score is given based on the number of species of traditional significance that are stil present. Maintaining cultural practices, such as the gathering of mahinga kai, is an important way of ensuring the transfer of cultural values through the generations.

3. Access to the site. Do Tāngata Whenua have physical and legal access to

the resources they want to gather?

4. Assessment of whether Tāngata Whenua would return to the site in the future

as they did in the past.

The four mahinga kai elements are then averaged to produce a single score between 1 and 5.

Component 3 – Cultural stream health

The cultural stream health measure is the average of 1–5 scores awarded to each of eight individual indicators:

1. Water quality

5. Riparian vegetation

2. Water clarity

6. Riverbed condition/sediment

3. Flow and habitat variety

7. Use of riparian margin

4. Catchment land use

8. Channel modification

The Overall Cultural Health Index

The three components are brought together in an overal Cultural Health Index score. When the CHI is calculated for a specific site, a score is generated and

expressed as: A-0 / 2.1 / 4.2 where:

A identifies the site as traditional (rather than a B for non-traditional)

0 indicates that Māori would not return to this site in the future (1 indicates

they would return)

2.1 is the mahinga kai score (score of 1-5)

4.2 is the overall evaluation of stream health (score of 1-5)

(Tipa & Tierney 2003 & 2006)

Stream Health Monitoring (SHMAK) Assessment

The Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit (SHMAK) was developed by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) in partnership with Federated Farmers of New Zealand and partly funded by the Ministry for the Environment (MfE) (Biggs et al 2000).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 15

An Iwi-SHMAK kit was also developed by NIWA in partnership with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and funded by MfE (Ogilvie & Penter 2001).

SHMAK allows the measurement of water flow/velocity, pH, temperature, conductivity, clarity, streambed composition, riparian vegetation, invertebrates, periphyton and catchment activity through the use of a number of monitoring instruments and the recording of data onto forms. The information collected is ranked using a scoring system to understand how healthy the stream is and how it may be changing over time.

SHMAK was used to collect the fol owing types of data and using the following methods:

Biological Data

Common and easily recognised biological indicator organisms known to be characteristic of certain stream health conditions were observed and/or counted, including:

Types of stream invertebrates (e.g., insects, snails).

Types of periphyton (algae/slimes on the bed of the stream).

This was achieved by scooping samples into containers and using an identification sheet to identify and record the different species present.

Stream Habitat Data

Measurements and observations of physical and chemical conditions at a monitoring site, consisting of:

Water velocity (measuring the time it takes an object to float a set distance

Water pH (using pH strips dipped in a separate water sample from the site); Water temperature (using a thermometer dipped in a separate water

Water conductivity (using a conductivity meter dipped in a separate water

Water clarity (using a water clarity tube fil ed with water from the site) Composition of the stream bed (by observation and estimation of

percentages of rocks, gravels, sand, plants, etc);

Presence and extent of loose, silty deposits on the stream bed (by

observation and estimation according to a set guide); and

Stream-bank vegetation at the site (by observation and estimation of

percentages of different types of vegetation).

Each monitoring observation was recorded on special forms and assigned a score. Individual factor scores were then combined to develop overal scores for stream habitat, invertebrates and periphyton health. An overal rating for sites was then calculated based on pre-determined rankings within the SHMAK methodology. These scores depend on the type of stream which is inturn based on the composition of the stream-bed and the relative abundance of fine substrates in the bed (Biggs et al 2000). SHMAK data was collected from all river and stream sites, except Avonhead and Westburn (no water), and Wigram Basin (incomplete data due to equipment failure).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 16

Electric Fishing

Electric Fishing is a method widely used to survey fish within wadeable rivers and streams. The method involves the use of a special y designed machine that creates an electric field in the water that temporarily stuns fish to facilitate their capture in nets for closer inspection and identification.

This study utilised the Kainga EFM 300 packset in-conjunction with a hand held scoop net and larger mesh net. The EFM 300 consists of a battery-powered

backpack generator unit, a fibreglass wand with cathode, and an earthing wire. The machine allows output voltage, frequency, and pulse width to be control ed and also incorporates a timer that records the number of minutes in use. The EFM 300 also includes four separate safety circuits to maximise user safety. Both machine and net operators wear ful length neoprene waders and rubber safety gloves, with cotton inners during surveying (NIWA 2007).

Surveys were typical y conducted over a 10-20 metre stretch of river at each monitoring site and involved one pass on each bank, taking between 10-20 minutes in total. Voltage settings were normally 300 volts and adjusted to optimise the electric field according to the indicator on the wand. Fish were scooped out, counted and inspected to ascertain the species type and record their general size, before being returned to the water. At some sites a selection of fish were also photographed. Data on fishing time, distance of river fished,

fish numbers, species and size were recorded on the fish section of the Takiwā site assessment form. Electric fishing data was not able to be gathered at a number of sites due to equipment failure or unavailability.

3.5 Background Research and Data Analysis A literature review was also undertaken as part of the study to gather information relevant to the Ngāi Tahu association with the Ihutai catchment. This was also done to gain an understanding of past environmental health and species occurrence as well as an appreciation of the environmental changes the estuary catchment has undergone. This research also provided information on the occurrence of traditional species at specific sites that is vital for the analysis and reporting of data for both the Takiwā and Cultural Health Index assessments.

After the fieldwork was concluded, data from the completed monitoring forms was loaded into the Takiwā database, from which scores for the Takiwā, Cultural Health Index and SHMAK assessments were calculated. These scores were then analysed and graphed using excel to show the relative rankings of the sites from very good to very poor. Other data was also extracted from the database in relation to the presence and abundance of native and exotic species and how these related to the relative scores of each site.

E.coli and anti-biotic resistance test results were obtained from Hil s Laboratories and the data entered into excel. The data was then assessed against national drinking water, shel fish gathering and recreational standards for E.coli and graphed to show the percentage of samples that passed and failed the different standards, as well as the percentage that had anti-biotic resistance.

These results are outlined and discussed in the following section, which begins with a review of the traditional association of Ngāi Tahu with the estuary and its catchment.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 17

4 Ngā Hua / Results

This section outlines the results of the monitoring fieldwork and subsequent analysis carried out within the study. It begins by giving a background to the association Ngāi Tahu have with Te Ihutai and its catchment that provides an overview of past environmental health and species occurrence within the Ihutai catchment.

4.1 Ngāi Tahu Association with the Ihutai catchment

Tai ki uta; Ihu tai maroro

From the nose of the tide back to the land;

To where the sea sinks down (on the continental shelf).

Te Ihutai is an area of immense cultural and historical importance to Tangata Whenua within the Christchurch and wider Canterbury area. The estuary not only provided vital access to waterways stretching from Te Waihora (Lake El esmere) to the Kowai River, and to the fishing grounds of Te Tai o Maha-a-nui (Pegasus Bay), but was a place of significant settlement and food gathering for Waitaha, Ngāti Mamoe and Ngāi Tahu for over 600 years. The food and resources taken from the estuary were also part of an important trade and social network between hapū and whānau throughout Te Waipounamu (the South Island) (Christchurch City Libraries 2006; Tau, Goodall, Palmer & Tau 1990).

The first settlers of Te Ihutai were Waitaha who lived in two principle kaika (vil ages) around the estuary, located at Te Raekura (near Redcliffs) and Te Kai a Te Karoro (near Jellicoe Park). This was followed by Ngāti Māmoe who occupied a settlement near the Estuary on Tauhinu Korokio (Mt Pleasant) during the 1500s. About one hundred years after this, Ngāi Tahu, under the chief Turakautahi, established Kaiapoi pā north of the Waimakariri, along with the settlement of Rāpaki in Whakaraupo, Lyttelton Harbour under, Te Rakiwhakaputa. While Ngāi Tahu did not live alongside the estuary itself, people from both Kaiapoi and Rāpaki visited and used the area extensively as a mahinga kai in a similar way to their predecessors (CCL 2006; Tau et al 1990).

During these times the estuary was known to support tuna (eels), kanakana (lamprey), inaka (whitebait), patiki (flounder) and pipi. Kumara and aruhe (edible fern root) were grown in the sandy soils at the mouth of the Ōtākaro / Avon River. Manuka weirs were built around the mouth of the rivers during the eel migrations and patiki were abundant in the mudflats across the middle of the estuary, an area called Waipatiki (CCL 2006; Tau et al 1990).

While the estuary itself provided an abundance of valuable food resources, equally important was the estuary‟s catchment, which was made up of an extensive network of springs, waterways, swamps, grasslands and lowland podocarp forests. The extent of this network, much of which was stil present at the time of European arrival, was captured on the 1856 „Black Map‟, as well as numerous written and visual records from this period (Christchurch City Council 2007; CCL 2007).

The 1856 map is shown on the following page, along with a number early scenes of Christchurch, highlighting past vegetation and waterways in the catchment.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 18

Figure 2. 1856 Black Map of Christchurch (CCC 2007)

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 19

Figure 3. 1850 sketch of the Canterbury Plains from the Bridle Path, Port Hil s, clearly showing the Heathcote River and the swamplands of early Christchurch (CCL 2007)

Figure 4. 1851 painting showing „The Bricks' – known as the first settlement on the plains & situated on the south bank of the Avon near the Barbados Street bridge (CCL 2007).

Figure 5. 1852 sketch of the Avon River showing Worcester Street bridge & early buildings (CCL 2007).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 20

Figure 6. 1870s photograph of a boat travelling on the Heathcote River (Ogilvie 1992).

Both the Ōtākaro (Avon River) and Ōpāwaho (Heathcote River) were highly regarded as mahinga kai by Waitaha, Ngāti Mamoe and Ngāi Tahu, who maintained a number of settlement and mahinga kai sites along these rivers. These included Puari (Inner city/High Court/Victoria Square area), Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Ōtautahi (Kilmore/Barbados St), Te Oranga (Horseshoe Lake) and Ōpāwaho (Opawa) (Tau et al 1990).

The importance of the Ihutai catchment and the mahinga kai it contained was highlighted by the claims of Hakopa Te Ata o Tu, Pita te Hori and others of Ngāi Tūāhuriri to the Native Land Court in 1868. They attempted to have traditionally significant sites put aside as mahinga kai reserves but were unsuccessful. This action effectively shut Ngāi Tahu out of the development of the city and ultimately, the subsequent management of the Ihutai catchment (Tau et al 1990; Tau 2000; Matunga 2000; Pauling 2006).

The taking of the Te Ihutai Māori Reserve in 1956 under the Public Works Act as part of the Christchurch sewage works development and the subsequent discharge of human effluent into the estuary further compounded the situation. So important were the sites and the integrity of the mahinga kai found there, that the owners of the reserve would not accept the money offered as compensation, because they believed that only an area of land having similar characteristics to that which was taken would be adequate recompense (Tau et al 1990).

A number of catchment sites were also recorded as significant sites by Ngāi Tahu elders in information gathered by H.K Taiaroa during the time of the 1879 Smith-Nairn Commission. This information is particularly important as it included lists of the flora and fauna taken as mahinga kai at the specific sites. As Tau (2006, p12) states "these lists are critical because they are the earliest written records from Ngāi Tahu elders that al ow us to construct a picture of what the landscape was like". Traditional Species recorded from these lists for the Ihutai catchment include:

Freshwater Fish: Tuna (eels), Kanakana (lampreys), Kokopū, Inaka

(whitebait), Waikoura (freshwater crayfish), pipiki and hao (eel).

Plants: Aruhe (fernroot), Whinau (hinau), Pōkākā, Matai, Kahikatea, Kōrari

(flowering flax stalks), Kāuru (cabbage tree root), Tutu, Kumara.

Birds: Kererū (wood pigeon), Kākā, Kōkō (tui), Koparapara (bellbird),

Mohotatai (banded rail), Parera (grey duck), Pūtakitaki (paradise duck),

Rāipo (scaup), Pāteke (brown teal), Tataa (spoonbil duck).

Other: Kiore (rat) (Taiaroa 1880).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 21

From the literature review, a list of traditional y significant sites within the Ihutai catchment and the types of mahinga kai species traditionally found there are shown below.

Location

Mahinga Kai

Reference

Upper Riccarton,

A settlement and food

Tuna, Aruhe, Hīnau,

Pōkākā, Kanakana,

Locality in Bryndwr

A settlement and food

Kāuru, Aruhe, Inaka, Tau 1994

A settlement and food

Kāuru, Aruhe, Inaka, Tau 1994

Locality in Harewood

A settlement and food

Kāuru, Aruhe, Inaka, Tau 1994

A settlement and food

Matai, Pōkākā, Kahikatea, Kererū,

Koparapara, Mohotatai

On the banks of the

Waitaha pā with associated Tuna, Inaka,

urupā. Ngāi Tahu mahinga

Kokopū, Kokopara,

modern day Carlton

kai site. Market (Victoria)

Parera, Pūtakitaki

Mill Corner, past

Square used by Ngāi

Victoria Square to the Tūāhuriri to sell produce loop in the Avon near grown at Tuahiwi to early Lichfield Street

Little Hagley Park

A temporary whare site

used on journeys between

Avenue and Carlton

Kaiapoi and Banks

Peninsula and during the

operation of Market Square

Between Barbados

The pā of Te Potiki Tautahi of Tuna, Inaka,

and Kilmore Streets

Kōkopu, Kūmara,

Aruhe, Pārera, Rāipo Pūtakitaki,

The site of a significant

settlement called Te

Bottle Lake Forest

A significant coastal lagoon

used as a mahinga kai

QE I park, near Travis

Kaika or settlement site

Shark (at certain

within an extensive wetland

times), other marine CCL 2007

area that was often

connected to the sea.

Ngāi Tahu „outpost‟ (waho)

present day Judges

pā that provided a resting

Inaka, Mātā, Aruhe, Tau et al 1990

Street and Vincent

place on the journey from

Tutu. Also Kokopū,

Rāpaki to Kaiapoi, known as Waikoura, herrings

Pohoareare in earlier times

A settlement and food

Waikoura, Pipiki,

Kāuru, Aruhe, Kiore, Tutu.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 22

4.2 Takiwā Site Assessments Takiwā assessment results for the Ihutai catchment were poor. Of the 30 sites assessed, 64% were found to be of poor health, with a further 13% being rated as very poor. No sites were rated as good or very good, however 23% of sites were rated as moderate. Site results are shown in the graph below.

Ihutai Takiwā Scores

Te Ra Rapa New Ba/Ca

Overall, the Avon River catchment rated slightly higher than the Heathcote River catchment, having a greater proportion of moderately ranked sites as well as a higher total average score across its catchment sites. However, the Heathcote river catchment did achieve better scores for native species abundance, largely due to the greater presence of native riparian vegetation when compared with the Avon (see section 4.5 for more detail).

Estuary edge site results were mixed having 1 moderate, 3 poor and 1 very poor site. Coastal site ratings resulted in 1 moderate and 1 poorly ranked site. Both estuary and coastal sites scored poorly in relation to native species abundance.

Only 3 sites, Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Te Karoro Karoro (South Brighton Spit) and Tuawera (Cave Rock/Sumner), were considered healthy enough to return to.

The highest scoring site across al sites was Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush) (2.8/5). This was fol owed by Te Karoro Karoro (South Brighton Spit) (2.6/5), Ōruapaeroa (Travis Wetland) (2.3/5), and Waikākāriki (Horseshoe Lake), Jellie Park, Templetons Road and Tuawera (Cave Rock/Sumner Beach) (all 2.1/5). At the other extreme, four sites achieved the lowest equal score of 1.0/5. These included Avonhead, Owles Terrace, Woolston Industrial Estate and the Estuary Outfal .

Full results for the Takiwā assessments are included as Appendix D, as well as a full record of site photographs (Appendix H).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 23

4.3 CHI and SHMAK Freshwater Assessments CHI and SHMAK results for the Ihutai catchment were also poor and supported the Takiwā assessments outlined above. However, because these assessments focused on the health of freshwater resources at a site they highlighted a number of specific issues of significance to the health of the catchment.

The CHI rated 73% of al sites as poor to very poor with the remaining 27% being moderate, while the SHMAK rated 66% of sites as poor to very poor, 17% as moderate and the remaining 17% as good to very good.

The highest scoring site under the CHI was Jel ie Park (B-0 2.8 3.0) followed by Pūtarikamotu (A-1 3.0, 2.0), Templetons Road (B-0 2.8 2.1) and Waipapa (Little Hagley Park) (A-0 2.0 2.4).

Ihutai CHI Scores and Takiwā Comparison

The highest scoring site under the SHMAK was Waipapa (Little Hagley Park) (41.3 & 7), followed by Pūtarikamotu (33.5 & 5), while Jellie Park had the highest stream habitat score of 64.4.

Ihutai Catchment SHMAK Scores

Although being poor overal , both sets of results showed that water quality in the Avon catchment was healthier than the Heathcote, particularly in relation to water clarity and sedimentation. A major factor in this result is the nature of the water sources and inputs feeding each catchment. From the site assessments, it was obvious that the Avon is heavily influenced by springs, while the Heathcote is influenced to a greater extent by stormwater inputs, including a major input feeding the headwaters at Wilmers Rd/Warren Park.

Full results for the CHI and SHMAK assessments are included as Appendices E and F respectively.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 24

4.4 E.coli Water Testing and Anti-biotic Resistence E.coli results within the Ihutai catchment were very poor, with 43% of all sites failing the recreational standard for water quality (260 E.coli/100mls) and only 7% or 2 sites, South Brighton Spit and Shag Rock, achieving the shel fish/food gathering standard (4-14 E.coli/100mls). No sites were fit for drinking. Moreover, a number of sites had alarmingly high results, the worst being Annex Road (1842 E.coli/100mls), at 7 times the recreational standard. Moreover, E.coli at this site were resistant to 2 different strains of antibiotics (Ampicil in and Tetracycline).

E.coli at 32% of al sites sampled (9 out of 28) showed resistance to antibiotics, with Ampicil in being the most common (all 9 cases), as well as Sulpha and Tetracycline in 1 case each. Anti-biotic resistant e.coli was found at sites throughout the catchment, indicating widespread contamination, including: Dudley Creek, Waikākāriki, Ōruapaeroa (Avon), Wilmers Rd, Wigram Basin, Annex Rd, Pioneer Stadium, Woolston Estate and Ferrymead (Heathcote).

These results are shown in the graph below.

Ihutai Catchment E.coli Results

olston Industrial E

E.coli results for river sites were worse than those for estuary or coastal sites, with the exception of two spring influenced river sites, Templetons Road and Jellie Park, which were relatively low. The Te Karoro Karoro (South Brighton Spit) and Rapanui (Shag Rock) sites were the only sites to achieve the shel fish gathering standard, both being estuary mouth sites with significant coastal water influences, while the Heathcote results were poorer than those for the Avon.

The frequency and distribution of Ampicil in in the samples is particularly disturbing because it is an anti-biotic of the penicil in group most commonly used by humans to treat bacterial infections, indicating human sourced contamination in the catchment. Sulpha group antibiotics (found at Wilmers Rd) are an older type of anti-biotic used extensively in both human and animal medicine, including cattle and poultry farming. Tetracycline (found at Annex Road) is another older anti-biotic used most extensively in agriculture, and to a lesser extent in humans.

These results warrant further investigation into the sources of these contaminants as wel as remediation work to eliminate them from the catchment.

Full results for the E.coli testing are included as Appendix G.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 25

4.5 Native Species Abundance Native species abundance indicators measured for al sites included the abundance of native plant, bird and fish species minus the abundance of exotic species, the comparative numbers of traditional and contemporary species present and the dominance of native vegetation at each site.

Native species abundance in the Ihutai catchment was poor, with 30% of all sites achieving the lowest score across al three abundance indicators. As stated in section 4.1 above, the Heathcote River catchment achieved the highest overal native species abundance scores, followed closely by the Avon river catchment. Estuary and coastal sites were the poorest, demonstrating the greatest extent of exotic species invasion, as well as pest and weed problems.

Ōruapaeroa (Travis Wetland) was the best site for native species abundance having both remnant and restored native vegetation as wel as various native bird species present. Next best were Westmorland, Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Templetons Road and Waikākāriki (Horseshoe Lake).

Combined species abundance scores for al sites are shown on the graph below.

Ihutai Combined Native Species Abundance Scores

Te Ra Rapa New Ba/Ca

In terms of native vegetation dominance, results were very poor. 70% of all sites had less than 15% of the total vegetation cover as natives, with a further 13% of sites being between 16 to 35% dominant. 17% had moderate native vegetation dominance (between 35-65% dominant), but there were no sites with greater than 40% of native vegetation dominance.

Native Vegetation Dominance across Ihutai Sites

Very Good 90%+Good 66-89%

Moderate 36-65%Poor 16-35%Very Poor 0-15%

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 26

Of the native plants distributed within the catchment, Harakeke (flax) and Ti Kouka (cabbage tree) were the most prevalent, being found at 21 sites. Pātiti or carex species were also common within the inland river sites, while Ngaio, Akeake and Saltmarsh Ribbonwood were common species found at estuarine and coastal sites. Surprisingly, 6 sites supported Kahikatea and/or Totara including Jellie Park, Athol Terrace, Pūtarikmotu, Ōruapaeroa, Westmorland and Templetons Road, highlighting some good native plant protection and restoration work done within the catchment.

Piwakawaka (Fantail) and Akiaki (red-bil ed gull) were that most commonly encountered native bird species, being found at 6 sites. Piwakawaka being confined to inland river catchment sites and Akiaki being found at estuarine and coastal sites. Pūtakitaki (paradise duck) were the next most common bird being found at 4 sites across the entire catchment. A solitary Korimako (Bel bird) was encountered at the Waikākāriki (Horseshoe Lake) site only. Ōruapaeroa (Travis Wetland) and Te Kai a Te Karoro (Jellicoe Reserve area) were the most abundant sites for native birds, being largely native ducks and/or waders. Overall, however, native bird abundance was disappointing.

While not all freshwater sites were electric fished, of the 13 that were, native freshwater fish were found at 7 of them. Tuna (eels), and in particular shortfin eels were found at al 7 of these sites, while longfin eels and common bul y were found at 2 of these sites. The Ōpāwaho site had the greatest diversity and abundance of native freshwater fish, followed by Pioneer Stadium and Westmorland. Waikākāriki, Travis Wetland, Owles Terrace and the Woolston Industrial sites were absent of any native fish. While native fish were present within the Avon and Heathcote rivers, the health of the waterways were not considered good enough to harvest from.

The most common exotic plants encountered during the fieldwork were exotic pasture grasses and weeds (24 sites) and Wil ow (13 sites, with 8 being in the Avon catchment). Other exotic plants encountered at more the 5 sites included Poplar, Oak and Silver Birch. Macrocarpa and Pampas grass were common exotic plants at the estuary and coastal sites. A single Brown Trout was found at the Westmorland site, while Blackbirds, Sparrows, Mallard Ducks and Rock Pigeons were found at a number of sites throughout the catchment.

4.6 Discussion When taking into account the results of all types of assessments undertaken, the cultural health of the Ihutai catchment is considered to be poor to very poor.

From the assessments and analysis undertaken, major factors both positively and negatively influencing cultural health within the catchment have been able to be identified, and provide the basis for the potential actions that may improve the cultural health of the Ihutai catchment into the future.

Factors associated with higher ranking sites and scoring included:

the presence and abundance of remnant and/or restored native

vegetation (eg. Pūtarikamotu, Travis Wetland, Horseshoe Lake, Jellie Park, Little Hagley Park, Templetons Road and Westmorland);

the influence of freshwater springs or coastal waters (eg. Jellie Park,

Templetons Road, and Te Karoro Karoro); and

the separation of the site from intensive urban or rural landuse (eg. Te Karoro

Karoro and Travis Wetland).

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 27

Factors associated with lower ranking sites and scoring included:

the absence of water or river flow (eg. Avonhead, Westburn, Dudley Creek); the influence of direct or visible stormwater inputs or wastewater discharges

(eg. Wilmers Rd/Warren Park, Horseshoe Lake, Travis Wetland, Wigram Basin, Annex Road, Woolston Estate, and Estuary Outfal ); and

the occurrence of extreme sedimentation (eg. Ōtautahi, Kerrs Reach, Owles

Terrace, Annex Road, Ōpāwaho and Woolston Estate).

Overall, the biggest influence on poor catchment health is the historical and continuing impacts of drainage and untreated stormwater. The impacts of historical drainage were obvious at a number of sites, leaving dramatic and thick sedimentation, particularly in the lower and tidal zones of both river catchments and into the estuary. Ongoing stormwater inputs were also obvious at a number of sites, causing the clouding of water and conspicuous deposits on the streambed. The most striking example of this was the stormwater drain feeding the headwaters of the Heathcote River at Warren Park/Wilmers Road. Another example of note is Horseshoe Lake, where four stormwater inputs drain urban and rural lands from Shirley, Burwood and some of the Marshlands area into this significant traditional food gathering area.

Drains or waterways? These photos show common scenes of the upper Avon and Heathcote Rivers,

where natural waterways, now resemble drains. L-R: Wilmers Rd area; Dudley Creek & Wigram Rd area.

Another significant issue is the loss original native vegetation cover, including the extensive wetlands and grasslands as well as podocarp forests of pre-and early European Christchurch. While a lack of native vegetation was common throughout the catchment, particularly around the estuary itself, where areas of native vegetation stil remain, or have been restored, such as Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Ōruapaeroa (Travis Wetland), Waikākāriki (Horseshoe Lake) and the Wigram Basin, they are viewed as taonga and offer potential for the future.

He taonga: Native vegetation protection and restoration at Ōruapaeroa / Travis Wetland

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 28

Generally, river sites, in particular specific sites in the Avon catchment and the riparian margin of the Heathcote catchment were better than those of the estuary and coast. Furthermore, native plant restoration work of the City Council was evident at a number of sites including, Jellie Park, the Wigram Basin (including Templetons Road), Pioneer Stadium as well as New Brighton Beach, positively enhancing sites. Native vegetation was noticeably absent, however, around the estuary and at Sumner Beach.

Kei hea ngā rākau Māori? A common view of the Estuary edge showing

the dominance of exotic species and a lack of native vegetation.

Of note was the Westmorland site at Francis Reserve which offers a great example of urban park native vegetation restoration that incorporates both tall lowland forest species providing play areas for children and habitat for native birds and insects, and low grassland/wetland species providing a buffering zone for external inputs and habitat for native waterfowl and fish.

Francis Reserve: an excel ent example of urban park native vegetation

including both lowland forest and wetland species.

The final issue of significance is the loss of visible springs and water quantity from the catchment. This was especially evident in the upper areas of both river catchments. In particular, the upper areas of all Avon tributaries were completely dry. The most remarkable example of this was the Avonhead site across Russley Road, where an empty, grass covered 4-metre deep remnant river channel was encountered winded its way across private farmland to a bowl shaped spring-head area.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 29

He tohu i ngā wā o mua: a precious reminder of the past, the remnant

river channel found at the Avonhead site, just over Russley Road.

While visible springheads were rare, both rivers are stil obviously influenced by spring water, particularly the Avon, which has notable water clarity down to the estuarine area. In a way, this springwater helps to „subsidise‟ the health of the catchment. Furthermore, two remaining springhead areas of significance were found at Jellie Park and Templetons Road. Again, these are considered taonga and offer potential for the future, if protected and restored.

He puna wai; He tohu oranga: water spring sites at Jel ie Park (left) and Templetons Road (right)

showing potential for future protection, restoration and enhancement.

A full list of recommendations for the future management of the Ihutai catchment, based on these findings are outlined in the fol owing section along with the overall conclusions of the study.

Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary 30

5 Te Whakamutunga / Conclusions

While the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and its catchment are important historical, cultural, recreational and ecological features of the Christchurch and wider Canterbury area, they have suffered the indignity of being dramatical y altered to support the growth of a city that is only beginning to realise the extent of this change.

This report outlines the results of a cultural health study for the Ihutai catchment undertaken by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu in-conjunction with members of Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Ngāti Wheke aimed at quantifying how Tangata Whenua view the current health of the catchment as well as understanding the extent of change in the catchment since European settlement.

Overall, the results of the study using the Takiwā assessment tool and a number of other assessment methods found the catchment to be in a state of poor to very poor cultural health. This was most poignantly highlighted by only 3 sites being considered good enough to return to under the Takiwā and CHI assessments. SHMAK and E.coli results further reinforced this overal assessment.

In particular, the impacts of historical and ongoing drainage and untreated stormwater, the loss of native vegetation, including wetlands, grasslands and lowland podocarp forests, and the decline of water quantity within the catchment were identified as major issues influencing this assessment. Of most concern were the E.coli and antibiotic resistance results which show widespread contamination from both human and agricultural sources in the catchment.

Although the catchment received a poor assessment, a number of sites and features were seen as positive and provide ideas for how future management may be able to improve the cultural health of the Ihutai catchment. These included the presence and abundance of remnant and/or restored native vegetation at sites such as Pūtarikamotu (Deans Bush), Waikākāriki (Horseshoe Lake), Ōruapaeroa (Travis Wetland), the Wigram Basin and Westmorland as well as the occurrence of freshwater springs at Jellie Park and Templetons Rd.

Protecting, enhancing and extending such areas and features and dealing with sources of contaminants wil be the most important challenges for the future management of the Ihutai catchment.

5.1 Recommendations

1. That all waterways, including drains are treated with the same standards and

managed for shel fish/food gathering into the future.

2. Increased protection and enhancement of waterways in the catchment

through the development of „native riparian buffer zones‟ in al currently unplanted public/council owned areas. These buffer zones should be at least 20 metres wide and planted according to Christchurch City Council streamside planting guide, and/or fenced where appropriate.